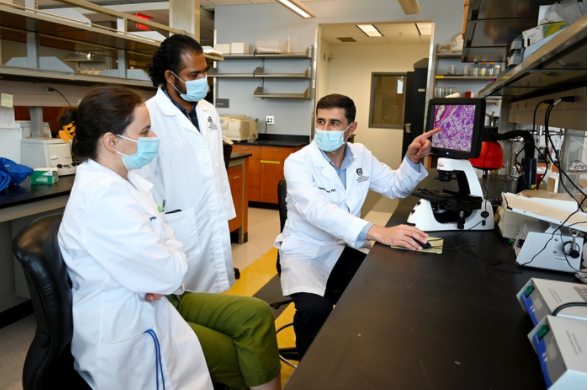

From L-R: Dr. Fulya Alkan, PhD (sitting), a postdoctoral fellow, Kazi Rafsan Radeen (standing) a graduate student in Augusta University’s Biochemistry and Cancer Biology graduate program, and Dr. Hasan Korkaya (sitting) in Korkaya’s Lab. Photo courtesy of Michael Holahan, Augusta University

October 4, 2021 — Understanding the role a certain molecule plays in both cancer cells, as well as the cells tasked to kill foreign invaders in the body could be the key to unlocking the benefits of treatment for one of the most aggressive forms of breast cancer.

“Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) gets its name from the fact that these cancer cells do not have estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors, and do not produce very much of the oncogene called HER2,” said Hasan Korkaya, DVM, Ph.D., an associate professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at the Medical College of Georgia. “This form of cancer is usually diagnosed more frequently in African American women under the age of 40 and those women who test positive for the BRCA-1 gene and display even more aggressive disease than their Caucasian counterparts.”

According to the American Cancer Society, around 10-15% of breast cancers are triple-negative breast cancer. As part of a $1,761,375 grant from the National Cancer Institute, Korkaya and his research team at the Georgia Cancer Center will be studying a molecule found on both the cancer cells, as well as the white blood cells tasked with attacking and killing the cancer cells before they can move from the breast to vital organs like the lung, brain, or liver and grow leading to an increased risk of death for the cancer patient.

“In cancer research, we want to understand this metastasis to learn how tumor cells can spread from the primary tumor, survive in the circulation system against the immune system’s attempt to kill them, and colonize secondary organs to grow new tumors,” Korkaya said. “This new grant will allow us to study the tumor cells and tumor entrained immune cells, as well as the microenvironment inside those secondary organs to see what they contain that allows the tumor cells to thrive.”

Previous studies in cancer research have shown how important the HSP-70 molecule is in protecting the cancer cell from being attacked and destroyed by the conventional therapies as well as immunotherapy. But Korkaya believes HSP-70 is just as important and maybe even more important in tumor entrained immune cells that suppress the anti-tumorigenic responses of immune system and therefore blocking HSP70 can reactivate the immune system enhancing the efficacies of existing chemotherapy and immunotherapy treatments for triple-negative breast cancer. Another aspect of Korkaya’s research is to show the role HSP-70 plays in creating a microenvironment that is ripe for tumor cell growth.

“We have pre-clinical models for triple-negative breast cancer, as well as samples from triple-negative breast cancer patients being treated at the Georgia Cancer Center that will be utilized to dissect molecular mechanisms and functional significance of the tumor microenvironment which is recognized to play a major role in metastatic process as part of this research project,” Korkaya said. “My hope, my wish, and my prayer are that our findings from this study will lead to new ways to use chemotherapy and immunotherapy to treat triple-negative breast cancer.”

For more information: www.augusta.edu/cancer

April 24, 2025

April 24, 2025