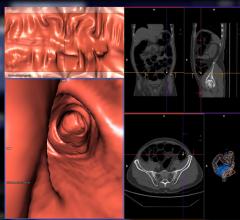

Atlas of Gastrointestinal Imaging: Radiologic-Endoscopic Correlation, by Perry Pickhardt, M.D., reconstructs the GI tract in 3-D.

A great divide has existed in gastrointestinal imaging, and it lies between radiologic and endoscopic imaging. These two fields have evolved along an analogous path that has recently come to a crossing as gastroenterologists are increasingly applying radiologic techniques, while radiologists are becoming “virtual endoscopists.”

“There is a need to fill in the glaring void in gastroenterological imaging,” stated Perry Pickhardt, M.D., associate professor of Radiology at The University of Wisconsin Medical School in Madison, in his recently released book Atlas of Gastrointestinal Imaging: Radiologic-Endoscopic Correlation.

“The seemingly disparate fields of radiology and gastroenterology have seen rapid parallel evolution, but are now beginning to intersect in terms of imaging. One obvious example is colonoscopy, where conventional and virtual techniques provide complementary evaluation. Another example is cholangiography and pancreatography, where MRCP and ERCP represent useful complements,” Dr. Pickhardt said.

He added that, “not only are radiologists becoming ‘virtual endoscopists’ through the use of advanced noninvasive cross-sectional imaging techniques, but gastroenterologists are becoming increasingly involved in radiologic techniques, such as endoscopic ultrasound.

“As GI imaging continues to merge, it is becoming increasingly important for each field to be very familiar with the other,” said Dr. Pickhardt.

Virtual Endoscopy Operates on the Fly

What is driving the crossover between radiology and gastroenterology is the merger of technologies. Such is the case with virtual endoscopy, a technique to navigate a virtual camera through a 3-D reconstruction of a patient’s anatomy for the exploration of the internal structures to assist in surgical planning.

Recently, virtual endoscopy has advanced significantly through innovative IT solutions. In particular, a software program called the 3D Slicer designed initially to facilitate diagnostic and surgical planning for neurosurgery, now is doing the same for phases of endoscopic procedures. Born out of a collaboration between MIT AI Lab and the Surgical Planning Laboratory at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the program enables the surgeon to visualize a 3-D model of an anatomical structure acquired through computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) data and define a trajectory path inside the model in order to perform a virtual exploration to simulate endoscopy.

The visualization program has also enhanced techniques for virtual colonoscopy (VC), also called CT colonography (CTC). The 3D Slicer for virtual colonoscopy applies an automatic path-planning algorithm used to produce a colon fly-through. As the virtual camera flies through the model, the surgeon tracks the position of the virtual camera inside the model displayed on an LCD monitor and views the endoscopic camera’s perspective on another screen. The surgeon can also track the position of the camera on grayscale 2-D slices. The advantage of virtual exploration is that the surgeon can noninvasively perform a diagnosis using patient-specific data.

In a clinical study, researchers used the 3D Slicer solution to perform virtual colonoscopy on a 66-year-old female patient. The original source for the colon surface was an axial helical CT scan. The patient had two real polyps and the team added phantom polyps in the data set that ranged in size from 4.9 to 7.2 mm. The 3-D model of the colon was color coded to provide supplemental information. Centerline points through the colon were extracted automatically and the virtual endoscopic tool created a fly-through path for the camera. All polyps can be clearly detected during the fly-through.

Unique in this software is its uses of an algorithm, developed by Steven Haker, Ph.D., to color code functional data that is overlaid on the anatomical data. Yet some experts are skeptical about the effectiveness of color mapping 3-D images. “Color mapping can be useful for demonstrating relative density, perfusion or some other feature at radiologic imaging. However, most color applied to 3-D ‘virtual reality’ imaging simply makes a prettier picture,” indicated Dr. Pickhardt.

Swimming Capsule Endoscopy

Whether in color or grayscale, 3-D imaging is expanding its applications and linking both radiology and gastroenterology to multiple clinical specialties. “In addition to CT colonography (or virtual colonoscopy), other emerging imaging tests include endoscopic ultrasound, capsule endoscopy and other CT applications, such as CT angiography and CT enterography (dedicated small bowel imaging). MR applications are analogous to CT,” noted Pickhardt.

Scanning the entire gastrointestinal tract (GI tract), from esophagus to colon, using capsule endoscopy is on a revolutionary track with the introduction of a swimming endoscope. The current capsule endoscope on the market is passive – it moves down the GI tract starting with parastatic movement of the esophagus. The problem, according to Nobuhiko Hata, Ph.D., assistant professor and technical director of Image Guided Therapy Program, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, is that you

cannot drive the capsule toward suspicious lesions nor can you position it to do more precise scrutiny of a lesion. Hata believes that the solution to the problem is to develop an actively steerable endoscope, and, to this end, he is developing swimming micro-robots – un-tethered endoscopes for transmitting images from inside the body.

“Our technology is unique in the sense that it swims. Others have developed an endoscope, rowing it through the GI tract, but we believe that a swimming tail is the most efficient way of delivering the energy from the outside and then converting it to a propulsion pulse to steer it in the GI tract,” said Hata. The propulsion is inspired by a novel propulsion theory based on flagellar motion and is achieved by creating a traveling wave along a tail made of piezoelectric material decomposed into the natural modes of the beam. According to Dr. Hata, three individual waving tails, controlled by a magnetic field, are designed to swim in any direction. The same concept is applied to MRI-guided endoscopy, where “it’s like a map showing you where you are when you are driving,” said Dr. Hata.

“Many of the existing capsule endoscopes are targeting just the small intestine, but our method can be used in other parts, including the esophagus and stomach because you can control the position of the endoscope,” noted Dr. Hata. “The person will be placed inside the MRI. Currently, capsule endoscopes take 10 hours to pass through the GI tract, but with this steering technology you can actually steer much faster through the GI tract.”

Virtual Colonoscopy vs. Optical Colonoscopy

Another area where radiologic and endoscopic imaging is fusing is in virtual colonoscopy (VC). Although optical colonoscopy remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of colorectal abnormalities, a close competitor is VC, which uses CT or MRI to produce 2-D and 3-D images of the colon to diagnose colon and bowel disease, including polyps, diverticulosis and cancer, and enables physicians to examine 90 to 95 percent of the colon.

In the first insurance-funded study on virtual colonoscopy, Dr. Pickhardt and his team screened 1,110 adults with an average age of 58 and found large or medium polyps in 10 percent of the patients. Of those patients, 71 required a second optical colonoscopy. In 65 of the 71 patients, the findings from standard colonoscopy and VC were the same.

“Our positive experience with virtual colonoscopy screening covered by health insurance demonstrates its enormous potential for increasing compliance for colorectal cancer prevention and screening,” said Dr. Pickhardt. This could also lead to VC becoming more common than or even replacing optical colonoscopy.

“I believe that VC will become a major component of screening in the near future. VC represents a safer, cheaper and sensitive filter for determining the minority of patients (~ five percent) that would benefit most from conventional colonoscopy, which remains the therapeutic study of choice,” Dr. Pickhardt added.

As emerging technologies in virtual endoscopy and VC prove increasingly effective, radiologic and endoscopic imaging will continue to close

the divide.

February 06, 2024

February 06, 2024