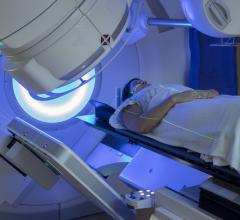

Attendees of ASTRO 2019 walked the halls of McCormick Place in Chicago, Ill.

At the American Society for Radiation Oncology’s (ASTRO) 2019 annual meeting, the society’s leadership introduced a new format for its Presidential Symposium.

Hundreds — if not thousands — flocked, to the general session room on opening morning, Sept. 15, for talks about whether metastatic disease could be cured with radiation therapy. Those were followed by a debate between community heavyweights who argued the pros and cons of the topic. This opening (or general) session was followed by 13 breakout or “learning” sessions, each focused on an aspect of the overall topic. Attendees were then directed for further discussion in the exhibit hall.

An Oxford-style debate, held at the end of the opening session, was orchestrated to boost engagement. “A debate is a great way to get people thinking more about what are really the issues at hands,” said Karyn A Goodman, M.D., who spoke earlier in the opening session. “Having the more scientific or data-driven talks to begin with gave a foundation for the debate.”

Goodman, a professor of radiation oncology at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City and associate director of clinical research at the hospital’s Tisch Cancer Institute, focused on the role of local therapies in managing patients with metastatic disease. Her talk was preceded by one on contemporary principles of metastatic cancer dissemination; and followed by a presentation whimsically dubbed “Finding the Unicorn” (whose subtitle was more in the mainstream: “The Abscopal Effect”).

Part 1 — The Opening

In her talk, Goodman noted how perspectives on metastatic disease have changed over the last century — particularly recent decades — and how those perspectives have impacted treatment. She focused particularly on local therapies, which involve a specific treatment such as radiation directed at tissues in a distinct area of the patient’s body.

Of major consequence for local therapies has been the understanding of oligometastasis, defined as tumors early in their progression that have five or fewer metastases and involve between one and two sites. The hope has been that local therapy extends the life of, or — ideally — cures, the patient with oligometastatic disease.

Focusing on the abscopal effect, Charles Drake, M.D., Ph.D., described how the immune system in patients with this type of cancer can augment the effects of radiation. In describing this effect, the professor of oncology and immunology at Columbia University’s Comprehensive Cancer Center in New York City emphasized that eliciting such an immunological effect rarely occurs — relating its occurrence to finding a unicorn.

The opening session closed with a debate between the pro and con sides of whether radiation therapy actually can cure metastatic disease. In the debate, believers and non-believers in the power of radiation therapy squared off.

Before the debate, moderator Ralph R. Weichselbaum, M.D., chair of the Department of Radiation and Cellular Oncology at the University of Chicago in Illinois, said he hoped “to call attention to the fact that radiotherapy can be used to cure for some patients with metastatic disease.” He succeeded.

At the end of the session, the audience voted using their cell phones on whether they believed that stereotactic ablative radiotherapy (SABR) “routinely cures patients with metastatic disease and, therefore, should be the standard of care for these patients.” The majority of respondents voted against the idea — 62 percent to 38 percent. Goodman said she believed the outcome was due partly to the phrasing of the question, in especially, use of the term “routine.”

“I think (the vote) was just by the facts that we have (now),” she said. SABR “certainly has potential benefits and may in the future have more of a curative role.”

Part 2 — Learning Sessions

More than a dozen learning sessions ranging from immunotherapy to artificial intelligence were conducted in rooms stretching across a corner of McCormick Place. Among the topics was whether immunotherapy would only be curative if delivered with radiation therapy. Another focused on whether biological and genetic markers comprise the only method for selecting patients for treatment with a combination of radiation and immunotherapy. Others dove into aspects of radiation therapy, radiopharmaceuticals and artificial intelligence (AI). In each, attendees were asked to “pick a side” about which they were passionate.

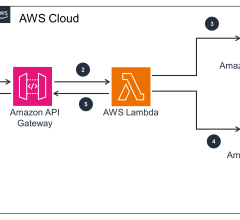

Those at the breakout session on AI gravitated to pro or con tables following two presentations on its role in the treatment of patients with metastatic disease. David Jaffray, Ph.D., the chief technology and digital officer at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, stated that machine learning has the potential to “discover new biological perspectives” by integrating complex clinical data. Kristy Brock, Ph.D., echoed Jaffray’s sentiment, stating that AI may be used to “optimize the acquisition and analysis of new data to further improve the efficacy of metastatic treatment.”

Brock, a researcher in the department of imaging physics at MD Anderson Cancer Center, said AI might help in the analysis of patient response to treatment. It might even assist in “determining the optimal treatments for individual patients,” she said in her presentation.

Small numbers. Attendees at the AI learning session — who numbered only about a tenth or fewer of those at the opening session — discussed whether AI might help identify patients with metastatic disease who would likely benefit from radiation therapy and how their treatments would be structured.

“We are trying to get an idea of how to use artificial intelligence (in the treatment of) metastatic disease with radiation,” group moderator Todd McNutt, Ph.D., told Imaging Technology News (ITN) during the session. McNutt said he hoped that the discussions might “inspire thought and get converse opinions to help drive the field forward.”

Friendly Fire. The comments came after discussions had been conducted at tables that spread across the room. Many who came to the AI session, however, gravitated to the chairs assembled in rows across the back of the room. Many of them used the relative quiet to check their cell phones … and then left the session.

As the number continued to dwindle, only about a hundred or so remained, a fact that Brock attributed to the unfamiliarity of interactive settings. “It is unfortunate that everyone didn’t stay and participate,” she said, “but I hope those that did, got a lot out of it.”

McNutt, an associate professor of radiation oncology physics and director of clinical informatics at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland, explained to attendees that the learning session would revolve around whether smart algorithms could help people effectively use complex information related to metastatic disease. Ultimately, he said, smart machines might help identify patients who would likely benefit from radiation therapy. Ultimately, smart machines might help select appropriate care plans for patients, he said.

These and other assertions were discussed at the tables. Pro and con opinions were presented at the end of the learning session.

How To Use Algorithms. One possibility receiving a lot of attention was the use of smart algorithms as “guard rails” to keep providers on track. These algorithms might run in the background of other software, coming to life only when providers exceeded certain bounds. “Knowing when the plan has deviated — and how — will help us,” said an AI proponent.

Alternatively, smart algorithms might autonomously draw organ and even tumor contours or assist in developing radiation plans, other proponents said. One cited an analogy of driverless car technologies that have spawned advanced features embedded today in modern vehicles. Much like advanced cruise control has become widely available ahead of driverless cars, so might selected capabilities in radiation oncology enter the mainstream. “These features will make us more aware of what is going on around us — make us better at treatment planning by helping us look at treatment goals,” one proponent said.

Cautionary Tales. There was, however, no shortage of cautions. Some were aimed at keeping people from believing too much in “black boxes,” the iconic symbols of AI algorithms whose decision-making processes are obscured from humans. Brock said this concern can be eliminated through the careful development of algorithms, telling ITN that “there are a lot of techniques that we can use to be able to understand what the algorithm is doing.” Other issues, however, were thornier.

Some AI antagonists questioned the basis of algorithm development, specifically the veracity of the data on which smart algorithms are trained. If data are not properly vetted, how could algorithms trained on them deliver results that should be accepted; would even extensive documentation of the decision-making processes of smart algorithms be enough if the data were not of sufficiently high quality, asked one AI antagonist.

A variation of this theme raised the possibility that human biases might contaminate the data, biases that were inadvertently introduced by the people who gathered the data. Consequently, the algorithms developed and trained on these data would be tainted, an AI antagonist said.

Even if effective, the use of AI algorithms could be negative. Human skills such as organ and tumor contouring might atrophy, according to one AI antagonist, if those tasks were delegated to algorithms.

Many possibilities. Metastatic disease has many variables, noted one participant. All the more reason smart algorithms are needed to help manage this information, said another. “AI will simplify questions,” said the AI proponent.

AI might have application in quantitative imaging to help evaluate metastatic disease and radiation therapy planning, said one. Another envisioned a future in which smart algorithms helped sequence hypofractionations for individual patients, providing a precision beyond what was humanly possible.

But, assuming that AI algorithms do, in fact, reach this level of performance one day, how will people know (to trust them), asked an attendee who described himself as neither pro nor con. “What level of understanding do we need?” he asked rhetorically.

The Brain Drain. By session’s end, proponents and antagonists weren’t just preaching to the choirs — they were the majority of those choirs. People had continued drifting out during the 90-minute breakout period until only one out of every seven or eight who walked into the room initially still remained.

McNutt said he hoped that “everybody listening and everybody participating would take the messages home and use them to drive both their clinical practice and research activities.” This would be essential, if smart algorithms are to gain traction in radiation oncology. Brock pointed out that AI in this field is mostly characterized by potential.

“If you talk to anyone who is in a radiation oncology clinic, very few are actually using (smart algorithms) clinically right now,” she said. “So there is a lot that we need to do to translate what we are doing in a research setting into a clinical setting.”

The MD Anderson professor of imaging physics expressed confidence, however, that AI would soon take hold: “I think that, absolutely, we are at the point that we can take some of these algorithms and use them as ‘guard rails.’ ”

Part 3 — One-on-Ones

Finally, as part of ASTRO’s re-engineered Presidential Symposium, participants were supposed to discuss their ideas further during “highly interactive” conversations. These were to go on after the learning sessions.

ASTRO envisioned these discussions as collegial, spanning academia, practitioners and industry. And they were to be as individual as the people who participated in them. They were billed as informal “table talks” — “where the real fun” was to begin.

ASTRO had assigned these extended conversations to be held in the Innovation Hub in the exhibit hall — an apparent effort to drive attendees to the exhibit floor.

Like the breakout learning sessions, the discussions would not be accredited for continuing medical education credits. (Only the first part of the Symposium — the opening or general session — was accredited, according to ASTRO.) As such, there appeared no verifiable way to be sure that such informal conversations had actually taken place.

But Brock said she believed the symposium had served its purpose, one that was unlike any of its predecessors — one she described as inspirational and pioneering. Consequently, they should continue, she said: “I think we need more nontraditional learning settings where we have this engagement.”

Greg Freiherr is a consulting editor to Imaging Technology News (ITN). Over the past three decades, he has served as business and technology editor for publications in medical imaging, as well as consulted for vendors, professional organizations, academia, and financial institutions.

April 14, 2025

April 14, 2025