Greg Freiherr has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service, The Freiherr Group.

Why Developing Multiple Screening Technologies is a Must

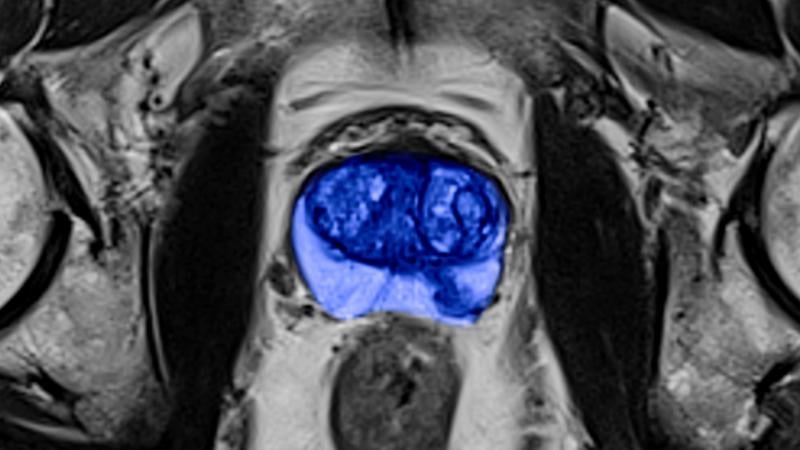

MR prostate image courtesy of Siemens Healthineers

Effective screening may be the key to America’s future. Only by catching disease early, before disease can injure the patient and impose financial penalties from lost work and medical expenses, can America achieve its dual goals of high-quality healthcare at low cost. Cancer, more than any other disease, exemplifies the promise and challenge.

Modern mammography screening may reduce deaths from breast cancer up to 28 percent. This success raises hope that similar gains might be made against other cancers. The use of computed tomography (CT) for lung screening and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for examining the prostate illustrate the two extremes of how this might be approached.

Low-dose CT lung screen has come in the wake of failed tests, namely chest X-rays and sputum cytology, neither of which has decreased lung cancer mortality. In contrast, prostate MRI is being pursued as one of several interlocking technologies and techniques that include digital exams performed by gloved physicians, PSA blood tests and ultrasound follow-up.

The latest MR advance is non-invasive, thanks to surface coils whose use streamlines patient set-up and accelerates scans. Adding to the future potential of prostate assessment are several positron emission tomography (PET) radiotracers that show promise for identifying prostate cancer, metastatic spread and relapse. Notably new opportunities are also arising in single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) and PET/MR.

Although screening, diagnosis and monitoring for prostate cancer are still very far from perfect, they exemplify where screening needs to go.

Know When to Fold ‘Em

Rather than depending entirely on a single imaging technology, as does CT lung screening, or heavily so, as does mammography, prostate screening is part of a multi-pronged approach that may provide the flexibility for developers to adjust their R&D and for healthcare strategists to fine tune protocols.

The advantage stems from the cautionary tale of putting all your eggs in one basket. Spreading those eggs around provides options. Just as importantly, having multiple options could help developers know when to quit — when to walk away from a technology that has gone sour and pursue more promising ones.

All too often innovators, having fallen in love with a technology, doggedly pursue it, wasting huge sums of money in the process. In the case of screening, this could do an even greater harm, delaying the development of effective screening tools.

The irony, of course, is that money can limit the development of multiple technologies, leading entrepreneurs to gamble on a “best bet.” Funding can be particularly problematic for publicly held companies, which must account for expenditures to shareholders. This is where a silent partner can come in handy. And there are few in a better position to play this role than the Federal government.

Through innovation grants, the Feds scatter seed money like a tech-savvy Johnny Appleseed. Among the sources: the Federal Laboratory Consortium for Technology Transfer, Small Business Innovation Research, Small Business Technology Transfer and Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research.

Those funds too are finite — and getting more so. But the argument for the Feds climbing onboard makes more sense than ever.

Turning to Uncle Sam

It goes like this. Value medicine has, at its core, an emphasis on prevention. As the population gets older, workers look to extend their livelihood (in fact, the economy, at least in the near term, is depending on it). The ability of healthcare to maintain worker viability will be essential. And it will have to be done cost-effectively. That means keeping a lid on medical expenses.

Better healthcare, improved quality of life, lower costs — it’s a challenging hat trick. And it can’t be done without disease prevention. And in that screening will be enormously important.

Medical imaging already has the core tool sets upon which to build. The current — and evolving — approach to prostate assessment shows where screening could go. CT lung screening will be a significant step in the same direction only if other technologies are brought in to complement it.

Screening is too important to America’s future to bet on single paths of technological development. We cannot simply wait for the right technology to plop serendipitously into our collective lap.

Editor's note: This is the second blog in a four-part series on screening. The first blog, “Screening: How New Looks at Old Modalities Might Turn Imaging Upside Down,” can be found here.

April 17, 2025

April 17, 2025