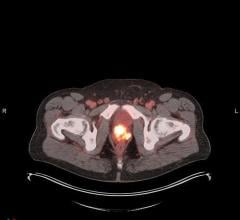

Molecular imaging with PET/CT is leading off a new era of personalized medicine (photo courtesy of GE Healthcare).

In an increasingly impersonal world, where Facebook counts the number of friends we have and texting takes the place of conversation, who would not want personalized medicine?

I liked it when visionaries first floated the idea more than a decade ago. That was when decoding the human genome was to be the cornerstone.

Looking into the genetic recesses of our humanity was to have revealed the differences among individuals, explaining why one person developed cancer while another did not. We were to gain an understanding of why some patients respond well to treatments when others do not, and learn how to best manage patients. We were told we might even be able to fix the faults in our genetic machinery and prevent some diseases altogether.

Well, that didn’t pan out.

Now we’re hearing again about personalized medicine, but this time what the purveyors of this term have in mind might just happen, thanks to some semantic sleight-of-hand and a heavy dose of innovation. Radiology, rather than genomics, will be the building block of this future.

Front and center will be molecular imaging with its increasing ability to quantify the uptake of biomarkers. This kind of number, namely standardized uptake values, has been around for a long time. But now positron emission therapy/computed tomography (PET/CT) quantitation is living up to its potential. It is distinguishing healthy from diseased tissue in a reliable and reproducible way, removing the uncertainty that goes with qualitative assessments and allowing the comparison of exams over time.

This capacity is being buoyed by an emerging legion of biomarkers that promises to dive into metabolic processes, providing possibly an unprecedented heads-up on disease and its extent.

It also might allow physicians to determine the effectiveness of therapy, as well as issue early warnings on the recurrence of disease signs after initially successful therapy.

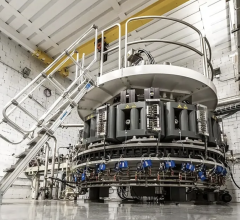

And there may be more opportunities to personalize medicine than just molecular imaging. One may be magnetic resonance (MR) “fingerprinting,” a quick, radically new kind of MR that might one day scan — in just a few minutes — whole patients for early signs of cancer, multiple sclerosis and heart disease, scanning that might be done on a standard high-field scanner.

This possibility took shape in mid-March with the online publication of results from Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland, where researchers using a 1.5T scanner generated a “fingerprint” of health. The technique, according to the researchers, amounts to “an alternative way to quantitatively detect and analyze complex changes that can represent physical alterations of a substance or early indicators of disease.”

These were obtained by varying the scanner’s electromagnetic field, producing signals carrying information about key physical properties of in vivo tissues. The signals were analyzed, quantified and charted against patterns associated with health or disease.

If the preliminary results hold up, MR fingerprinting would be the first truly novel MR development in decades. And the timing couldn’t be better, given the push for healthcare reform and its emphasis on cost reduction, disease prevention and early treatment.

It’s hard to say when — or even whether — the new possibilities coming out of radiology will rise to the hype generated by decoding the human genome. But that may not matter. Semantics have redefined the venue of personalized medicine along with its expectations.

It is encouraging in this context that the genomic home run mentality that used to characterize personalized medicine has begun to fade in favor of a radiological lineup that puts runners on base.

Play ball.

Greg Freiherr has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service, The Freiherr Group. Read more of his views on his blog at www.itnonline.com.

August 06, 2024

August 06, 2024