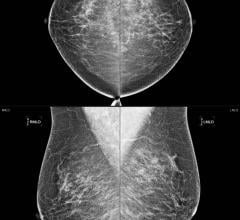

This mammogram shows an example of dense breast tissue.

Sutter Pacific Medical Foundation Women’s Health Center is in Santa Rosa, Calif., a community of 160,000 located an hour north of San Francisco in an area that is perhaps most prominently known as the Sonoma wine country. Our breast center, which screens 10,000 women per year, has established a regional reputation as a center of excellence in the detection and diagnosis of breast disease.

I have had the pleasure of being the medical director for the past eight years. An old friend and colleague, Tom Stavros, M.D., joined the center in 2009, and Arnold Honick, M.D., joined the staff in 2011. During the past year, we became more focused on breast density, because of increasing knowledge about how breast tissue density both increases a woman’s risk of breast cancer and tends to obscure our ability to “see” cancers on mammograms.

The governor of California, unfortunately, has vetoed recent legislation that mandated patient density notification effective April 1, 2012, but we will continue to notify women of their tissue density and provide adjuvant imaging where appropriate. Our experiences should be valuable to others who, by mandate or otherwise, notify women of their density and provide adjuvant screening imaging of any kind. The experience at our center primarily has been with ultrasound, but we find density to be an important part of the decision process to provide or recommend magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) screening as well.

We added SonoCiné automated screening breast ultrasound in 2010. Stavros, an investigator in the ACRIN 6666 trial 1 of adjuvant screening ultrasound, had become convinced of the ability of ultrasound to discover small cancers in women whose mammograms were “normal,” but who have dense breast tissue. Specifically, the published evidence, both from the ACRIN 6666 trial and other single and multi-center screening ultrasound trials, indicated that adding screening ultrasound exams for dense-breasted women found up to twice as many breast cancers and, on average, at half the size as was possible by relying on mammography alone.

Based on this evidence, our team decided to offer screening ultrasound examinations for women with high breast tissue density. As the number of women whose breast tissue can be classified as high density is about 40 percent of those who are eligible for screening mammography 2, as many as 4,000 of the current screening patients, we decided to use an automated technology for image acquisition. Whole breast ultrasound scanning would have been impossible for us, given the staffing requirements.

Adding ABUS a Learning Experience

Automated breast ultrasound (ABUS) is not reimbursed, and the expense of providing ABUS is not covered by the diagnostic breast ultrasound code (cpt 76645). We decided to inform all patients with high breast tissue density of their tissue density, the implications of dense tissue on risk and the sensitivity of the mammogram, and give them the option of having an ABUS procedure at a charge of $295. This charge is less than an RVU (relative value unit) analysis would indicate, but we wanted to keep the charge as low as we could to encourage usage. For patients without the means to pay, we have secured funding through gracious grants to our foundation.

At the time the SonoCiné unit was installed, the center was testing Volpara, an automated volumetric breast density assessment tool. Volpara uses the “for processing” image from the digital mammography unit to assess the volumetric density of the breast and also converts that density into Volpara Density Grades (VDG), which serve as a surrogate for the BI-RADS density categories. The Volpara assessments are available in the form of a secondary capture image, viewable with the screening images.

Before implementing density notification to the patient and ABUS, we provided information on the program to patients both by mail and in the center. We also informed referring physicians about the benefits of adjuvant screening ultrasound for their patients with dense tissue.

Our protocol provided for the invitation to all screening patients with dense tissue (BI-RADS density grade 3-4 or VDG 3-4) to receive an automated screening breast ultrasound. From this information base, we began to recruit appropriate patients by advising screening mammography patients at high density (VDG 3,4), with the patient report, of the availability of the ABUS exam, asking them to call to schedule the study. Essentially, these patients were recalled for the ABUS.

We found this approach — requiring the patient to take initiative in scheduling the supplemental exam — resulted in only about one patient per day, or 6 percent of eligible patients, scheduling and receiving the ABUS exam. We were concerned so few women were utilizing this beneficial service.

The influence of the patient-pay approach was, potentially, one explanation. But we had made provisions for women who did not have the means to pay for the supplemental ultrasound to receive the procedure, and use remained low. We knew that cancers were going undetected. We are all Tabar disciples and realized that the women we were not diagnosing would not receive the clear benefits of early detection and treatment.

To try to combat the low compliance rate, we decided to move the point of the patient density awareness from the patient report to the point-of-care. Volpara, which previously was available only on the interpretive workstation, was sent to the workstations in the mammography rooms as well. With the robust and objective density information available to our technologists, they could inform individual patients about their density while still in the mammography room. If she has high breast tissue density (VDG 3-4), we offer her the opportunity to schedule the supplementary exam, to be performed at a later date, before leaving the center. This approach improved the rate at which appropriate patients were scheduling to about two per day (12 percent). But it was clear we still hadn’t quite found the secret to increasing these numbers.

A Successful Outcome

We owe finding the secret to our terrific technologists. They recognized the time pressures on women and suggested it was time, not money, that was standing in the way of women having the ABUS procedure. They recommended giving women with high breast tissue density the opportunity to have the procedure before leaving the center. Predictably, administration balked at the additional staffing requirements. But we all decided to give the new process a try.

The suggestion worked. Daily ABUS volumes rapidly increased. While they have room to grow, we realize more education will be required before everyone understands the importance of this adjuvant procedure. Women are shown their Volpara density assessment before they leave the mammography room, and the dramatic increase in compliance with the recommendation for an ABUS examination shows their receptivity to new technology.

This also demonstrates an additional layer of complexity in the challenge of delivering care, both from the patient and the practice perspective. Women are committed to their healthcare, but time and expense are also concerns as they navigate their daily activities. From the center’s perspective, we learned we need to incorporate additional flexibility to meet patient needs.

As we gained more experience with ABUS, we also learned that acquiring both the screening mammogram and the ABUS images in the visit allows us to interpret all of the images side by side. This both eliminates the inevitable redundancy of reviewing the mammogram when a subsequent ABUS is performed and allows a more integrated approach to interpretation. Another important takeaway from our experience is that educating our patients and our referring physicians must be an ongoing priority.

There is a growing consensus that screening for breast cancer should be individualized for each woman, rather than being approached, as it is now, in a one-size-fits-all-manner. Breast tissue density has been shown to be both an independent risk factor for cancer and also an issue that decreases the sensitivity of the mammogram. 3

By providing women with their personal, objectively determined tissue density and making available to them the adjuvant imaging that can provide earlier detection, we believe we are making an important advance in reducing mortality. Our results here have shown patients accept the new paradigm for care, but that education of patients and, equally important, referring physicians, must remain a focus of effort until individualized care becomes not just better care, but also the standard-of-care.

References:

1. Berg W.A., Blume J.D., Cormack J.B., et al. “Combined screening with ultrasound and mammography vs mammography alone in women at elevated risk of breast cancer.” JAMA 2008; 299(18):2151-63

2. Stomper P.C., D’Souza D.J., DiNitto P.A., Arredondo M.A. “Analysis of parenchymal density on mammograms in 1,353 women 25-79 years old.” AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167(5):1261-1265.

3. Boyd N.F., Guo H., Martin L.F., et al. “Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer.” N Engl J Med, 2007; 356:227-36.

August 06, 2024

August 06, 2024