Greg Freiherr has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service, The Freiherr Group.

Trump Card in the Deck of Hybrids

In the yesteryears of over-optimism, when medical imaging was in its heyday, magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) was framed as a kind of digital phantom that would one day wrest the biopsy needle from the hands of oncologists. MRS, with its graphs and hard numbers characterizing the metabolites present in tissue, would illuminate the biochemical fingerprint of cancer.

That pipe dream went up in smoke as the 20th century drew to a close, when MRS advocates were seen as victims of the da Vinci syndrome – that ideas, while reasonable, were not feasible because technology was not yet up to the task. The past decade, however, has swept much of the technological challenge aside. The adoption of 3T, which began in earnest midway through the last decade, along with the evolution of 1.5T scanners with the horsepower to do MRS, has put spectroscopy at the fingertips of many in routine clinical practice. Vendors offer training courses in its use. Yet, very little has changed.

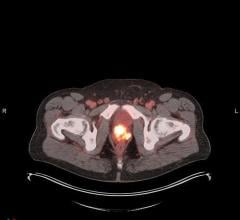

Despite a cornucopia of MRS packages – some so easy even a gecko could run them – spectroscopy remains largely a research tool, driven by forward-thinking, forward-looking visionaries. One reason is that long-repeated practices are hard to change…and needle biopsy is one of the longest. Another is that functional imaging, namely positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT), is widely available and its usage is still trending upward, albeit less so than a few years ago.

Given these incontrovertible facts, needle biopsy will likely remain the go-to procedure for definitively diagnosing cancer. And similarly, PET/CT will likely remain the modality of choice in diagnostic workup and patient followup after therapy.

Yet, a strong case can be made for routine use of MR spectroscopy in oncology, if for no other reasons than the convenience of the provider and better service to the patient. Virtually every oncology patient has at least one MR exam. With the right software and hardware in place, adding a six-minute sequence to the standard brain exam provides baseline numbers from healthy neighboring tissue while another six-minute sequence plumbs the nearby lesion, producing spectra that in many cases can distinguish healthy from malignant tissue.

Granted, these spectra will not supplant a needle biopsy. And the extra time and effort will not be reimbursed. Consequently, any additional costs to upgrade the scanner to support spectroscopy may be tough to justify. But this justification does not have to come from the need to generate revenue so much as to ensure its source. We are at a time when the value that radiology brings to medicine is being questioned. Tiny ultrasound scanners peek out from the shirt pockets of general practitioners; a 1980s rock band promotes digital radiography on a music video; CT scanners capable of every major radiological exam are going for well under a million dollars.

By contrast, MR spectroscopy remains firmly rooted in radiology. It’s fast. It’s relatively easy to understand – although its results take time to grasp. And its use demonstrates the commitment of radiologists to patient welfare, supplanting conventional thought, which is to judge therapeutic success on the basis of whether a lesion has grown or shrunk. The hard numbers derived from MRS could help determine whether a patient is responding just days after the start of therapy. Compare this instantaneity to the weeks or months that must pass before tumor growth or shrinkage is evident.

MR spectroscopy is the ultimate hybrid imaging technology, delivering both anatomical and functional imaging in a single exam. As such, it may not only be the most underplayed card in imaging’s deck, it could be trump.

August 06, 2024

August 06, 2024