November 1, 2016 — Specifically training oncologists and their patients to have high-quality discussions improves communication, but troubling gaps still exist between the two groups, according to a new study in JAMA Oncology.

The 265 patients who agreed to participate in the research project had been diagnosed with advanced cancer (stages 3 or 4). Researchers coached them about what to ask their doctors and how to voice their concerns. Doctors were also given state-of-the-art communications workshop training.

Results showed that those who received training were much more likely to ask questions, ask for clarification and express their views. This is important because 90 percent of patients say they want to be actively involved in their care, and most busy physicians realize they need help in this area and want the support, said the paper's corresponding author, Ronald Epstein, M.D., a leading authority on this topic and a University of Rochester professor of family medicine, psychiatry and oncology, and director of the Center for Communication and Disparities Research at UR.

Doctors and patients also had more clinically meaningful discussions around topics such as emotions and treatment choices, results showed. In fact, the trained group was nearly three times more likely than the untrained group to talk about difficult topics such as prognosis.

"We have shown in the first large study of its kind that it is possible to change the conversation in advanced cancer," Epstein said. "This is a huge first step."

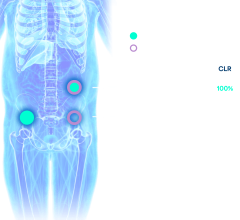

And yet despite the focused efforts, shared understanding about prognosis was lacking. For example, a few of the patients believed it was "100 percent likely" they would be cured, while one-third said it was "likely" they would be cured, despite their diagnoses of incurable cancer, and a majority thought they would be alive in two years. Median survival was just 16 months.

Being hopeful and having a realistic understanding of what to expect with advanced cancer are both important, Epstein said.

"We need to try harder to communicate well so that it's harder to miscommunicate," he said. "Simply having the conversation is not enough — the quality of the conversation will influence a mutual understanding between patients and their oncologists."

Until the end of 2016, researchers will continue to track the experiences of the families and caregivers of the deceased patients who took part in the study. Scientists are trying to learn whether the communications training had any impact on the families' grief experience and adjustment following the death of their loved ones, said Paul Duberstein, Ph.D., a co-author and professor of psychiatry and medicine at UR.

The communications coaching for oncologists included one-to-one mock office sessions with actors (known as standardized patients), video training and individualized feedback. Patients were given a booklet that Epstein's team wrote called "My Cancer Care: What Now? What Next? What I Prefer." Patients also met with social workers or nurses to discuss commonly asked questions and how to express their fears, for example, or how to be assertive and state their preferences.

Later, the researchers audio-recorded real sessions between the oncologists and patients, and asked both groups to fill out questionnaires. They coded the interactions and matched the scores to the goals of the training. Adult patients and their caregivers in western New York and Sacramento, Calif., were enrolled in the study from 2012 to 2014.

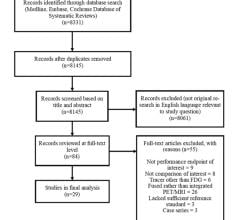

The study (called VOICE, for Values and Options in Cancer Care) was also randomized, meaning that approximately half of the physicians and patients received no special training and served as a control group.

The data also revealed that oncologists need better and more consistent training to address low health literacy by patients and "terror management," or the tendency to deal with fear of death through avoidance or selective attention, the study said.

One limitation of the study may've have been the timing of the training, which was only provided once, and not timed to key decision points during patients' trajectories. The effects of the training may have waned over the months, especially as the cancer progressed.

Doctors loved the intervention, Epstein added. Those in the "control" arm of the study requested to receive the training afterward, as well as fellows and other physicians at the UR's Wilmot Cancer Institute.

"We need to embed communication interventions into the fabric of everyday clinical care," Epstein said. "This does not take a lot of time, but in our audio-recordings there was precious little dialogue that reaffirmed the human experience and the needs of patients. The next step is to make good communication the rule, not the exception, so that cancer patients' voices can be heard."

For more information: www.jamanetwork.com/journals/jamaoncology

August 09, 2024

August 09, 2024