Greg Freiherr has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service, The Freiherr Group.

Screening: How New Looks at Old Modalities Might Turn Imaging Upside Down

Graphic courtesy Pixabay

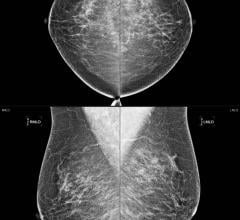

Cancer screening is the only circumstance in which apparently healthy people subject themselves purposely to an agent known to cause cancer. It is the paradox of mammography, a screening tool that has substantially reduced breast cancer morbidity, whose success has only added to its paradoxical nature.

While mammography may be the most recognizable type of screening, it is not the only one. Ultrasound is widely used to screen for cardiovascular disease, for example. But, unlike mammography, it does not rely on ionizing radiation. Nor does magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), an imaging tool deemed too expensive — and limited in scope — for use in screening. But that could change.

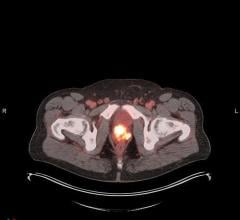

Consider GLINT (glucoCEST Imaging of Neoplastic Tumors) — an MR-based technique being developed to visualize the body’s use of glucose. GLINT imaging is based on the use by tumors of massive amounts of glucose. This concept underlies the ability of positron emission tomography (PET) to spot the presence and recurrence of tumors. But, whereas PET exposes patients to ionizing radiation through the use of glucose molecules tagged with positron-emitting fluorine (as well as the computed tomography (CT) with which it is commonly paired), GLINT records hot spots coming from the use of non-labeled glucose.

Too Early To Tell

In a May 24 press release announcing the GLINT program, Vienna-based European Institute for Biomedical Imaging Research (EIBIR) framed the technique as a “game changer for cancer screening.”

This possibility is as exciting, as it is speculative.

GLINT is only a few months old, its development having been formally launched in January this year. Its four-year development program, guided by EIBIR, involves major universities, research institutes and corporations in seven countries – one in Israel, the others in Europe.

GLINT is being groomed as an MR technique for finding disease. It may be especially useful against cancer. But also might be used for other diseases. It may be very inexpensive. (The GLINT project group claims that this technique might be six to ten times less expensive than current MR techniques.) But a need for glucose analogues could negate those savings.

Clearly, much about GLINT is up in the air. One thing is for sure, however. GLINT is not going to replace mammography any time soon. It may never do so, unless the technique can be developed for use on dedicated, low-cost screening devices. The capital investment underlying MRI is substantial, far more so than mammography or ultrasound.

Intriguing, however, is the metabolic basis of this technique, which promises to transform MRI from an anatomical modality into molecular imaging. The practical implications are huge. According to the project team, the development and commercialization of glucoCEST MRI will “benefit the global cancer population by improving the diagnostic accuracy of MRI and providing early readouts of treatment efficacy, leading to improved clinical decisions and outcomes.”

While economic considerations might blunt GLINT’s role in screening, they might work in its favor as a means to monitor patients for cancer recurrence following therapy. This would be especially so for pediatric patients who may be monitored using PET/CT and, consequently, exposed to ionizing radiation periodically during their formative years and long after. Notably, the research team is looking specifically at pediatric lymphomas, as well as squamous cell carcinoma and primary gliomas.

Much Potential, Little Proven

GLINT might be used on these and other cancers. Adding to its appeal is the possibility that GLINT might even be used to find diseases other than cancer, thanks to its ability to image proteins, according to Prof. Klaus Scheffler, Ph.D., of the Max Planck institute for Biological Cybernetics in Tübingen.

In the near term, multi-site research teams are concentrating on cancer and the detection of native glucose (D-glucose) uptake in tumors. They are also reportedly looking into glucose analogues, such as 3-oxy-methyl-D-glucose. Because methylated analogues of sugar cannot be metabolized, they might serve as tracers.

While such studies keep GLINT in the cancer wheelhouse, they raise questions about a basic premise underlying the development of this technique — its potential for low-cost exams. The use of such tracers would undoubtedly add to the expense.

Pushing such considerations aside is the exciting nature of GLINT — what its development signifies for the medical imaging community — that free thinkers are looking at an established modality not for what it is but for what it might be.

GLINT is the result of thinking outside the box, of asking “why not?” This begs the question: What other wonders of medical imaging might be similarly unlocked if the status quo is challenged?

Editor's note: This is the first blog in a four-part series on screening.

March 19, 2025

March 19, 2025