In order to estimate the effect of disulfiram pretreatment on brain accumulation of 64CuCl2, PET imaging studies were performed on Menkes disease model mice.

April 1, 2014 — Scientists at the Riken Center for Life Science Technologies in Kobe, Japan, have used PET (positron emission tomography) imaging to visualize the distribution of copper in the body, which is deregulated in the genetic disorder Menkes disease, using a mouse model. This study may lay the groundwork for PET imaging studies on human Menkes disease patients to identify new therapy options.

Menkes disease, though rare, is a fearsome genetic disorder. Most affected babies die within the first few years of life. The disease is caused by an inborn fault in the body's ability to absorb copper. The standard treatment today for the 1 in 100,000 babies affected by the disorder is to inject copper, but this therapy has limited efficacy. Eventually the treatment becomes ineffective, leading to neurodeneration, and the copper accumulates in the kidneys, sometimes leading to renal failure.

As a result, treatments have been sought that enhance the accumulation of injected copper into the brain while preventing its accumulation in the kidney. Recently, disulfiram, a drug developed to treat alcoholism, has been suggested as a therapy for Menkes disease, since one of its actions is to enhance this copper accumulation in the brain.

Now, in a study published in the Journal of Nuclear Medicine, scientists at the Riken Center for Life Science Technologies, in collaboration with pediatricians from Osaka City University and Teikyo University, have used PET to show that a combination of copper injections and disulfiram or D-penicillamine allows a greater movement of copper to the brain, where it is needed, without accumulating in the kidneys.

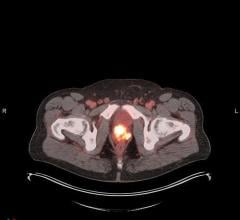

In the study, researchers used Menkes disease model mice, which have an inborn defect in copper metabolism, and injected copper-64, a radioactive isotope of copper, into the mice. They then used PET scanning, a non-invasive procedure, to visualize how the copper moved throughout the body. They compared mice injected with copper alone to mice injected with copper along with one of two other drugs, disulfiram or D-penicillamine, and the distribution of the copper throughout the body was observed for a four-hour period.

The results showed that the mice given copper along with disulfiram had a relatively high concentration of copper in the brain without a significant increase in the kidneys. Surprisingly, it showed that the amount of copper going to the brain in mice treated with disulfiram was actually higher than in those treated with copper alone, suggesting that the drug has an effect on the passage of copper through the blood-brain barrier.

According to Satoshi Nozaki, one of the co-authors, "This study demonstrates that PET imaging can be a useful tool for evaluating new treatments for Menkes disease. Based on this study, we are planning to conduct clinical PET studies of patient with Menkes disease."

For more information: www.riken.jp/en/

November 18, 2025

November 18, 2025