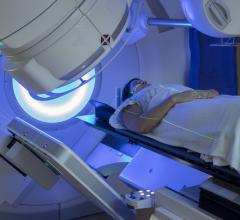

January 26, 2016 — A phase 1 trial examining precision hypofractionated radiation therapy (RT) in locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cases found that higher RT doses in a shorter time span were potentially cost-effective and generally well tolerated, while allowing for fewer radiation treatments. The study, “Precision hypofractionated radiation therapy in poor performing patients with non-small cell lung cancer: Phase 1 dose escalation trial,” was published in the International Journal of Radiation Oncology • Biology • Physics (Red Journal), the official scientific journal of the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO).

“Advanced radiotherapy technology, although requiring resources to acquire and thoughtful physician/staff training to operate, can lead to improvements in patient care and outcome, giving hope to even the most frail, at-risk cancer patients,” said lead author Robert Timmerman, M.D., University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas (UTSW). “And, somewhat surprisingly, this approach is shown to be very cost effective, which is welcomed in this era of difficult-to-control medical expenditures.”

The trial was conducted at the University of Texas Southwestern (UTSW) and Stanford University Medical Center. Kenneth D. Westover, M.D., Ph.D., also at UTSW, is first author on the study.

The standard of care in NSCLC cases is concurrent chemoradiation, with an absolute survival benefit of 4 percent to 7 percent at 5 years compared to sequential chemotherapy and RT, the study authors reported. Patients experiencing medical comorbidities or cancer-associated decline cannot always receive concurrent chemoradiation treatment because side effects negate potential benefits. For those patients, hypofractionated RT is another option, study authors said.

However, its past use has been fraught with the limitations of older technology, with shortened treatments causing excessive toxicity. The current study was designed to examine the use of hypofractionation with modern, advanced radiotherapy planning and delivery technologies including image guidance, intensity modulation and adaptation.

“It was previously shown that patients with earlier stages of lung cancer could have very effective treatment completed in fewer than five non-invasive treatments by using more modern, advanced and precise technology to direct the beams,” Timmerman said. “We specifically tested this novel therapy in the frailest patients, the so-called poor-performing patients, who are usually not allowed into clinical trials.”

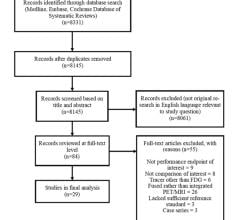

The study examined 55 patients with stage II to IV or recurrent NSCLC and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 2 or greater who were not candidates for surgical resection, stereotactic radiation or concurrent chemoradiation. Median age was 70 years old. Sixty-seven percent of patients were male. Seventy percent had a greater than or equal to 30 pack-year smoking history. Tumors in this patient population were large, on average, and commonly localized to the right upper lobe. Approximately 25 percent of patients were stage IV, and the majority of patients were stage III.

The trial’s primary endpoint was to determine the maximally tolerated dose (MTD), which was defined as “an unacceptable G3 or higher treatment-related, protocol-specified, adverse event (dose-limiting toxicities [DLT]), and defined according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v.3.0.” MTD was exceeded if 33 percent of evaluable patients experienced DLTs in the time measured.

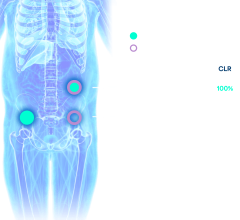

In the study, highly conformal radiation therapy was used in 15 fractions to a total of 50, 55 or 60Gy doses. Of the 55 patients, 15 received 50Gy dose level treatment, 21 received 55Gy dose level treatment and 19 received 60Gy dose level treatment. Of those, the 60Gy arm had the most stage IV disease, at 32 percent, but the amount was not statistically significant.

Study subjects had to experience a treatment-related DLT or survive 90 days to be evaluable. Doses were escalated when the last patient enrolled to that dose level had completed a minimum of 90 days’ follow-up without experiencing a DLT.

Patients were permitted to undergo chemotherapy after radiation, per consultation with a treating physician.

A 90-day follow-up was completed in all three dose level treatment groups without exceeding the MTD. Because the MTD was not reached, it could be possible that higher doses, according to the definition of the trial, might also be safe, study authors said.

The median follow-up was 12.5 months. At that point, 93 grade of greater than or equal to 3 adverse events had occurred, including 39 deaths. Most of the adverse events were considered related to factors other than radiation therapy. Median overall survival was 6 months with no significant differences between dose levels (P=.59).

Study authors found that results could suggest that a hypofractionated regime is safely delivered with photons rather than particle therapy or other specialized techniques, which could have implications for resource allocation.

They also reported that the potential in cost savings from the reduced treatment schedule could be an added benefit of a hypofractionated regime. The current duration of standard RT in locally advanced lung cancer cases is 30-40 treatments for six to eight weeks, compared to the 15 treatments administered over three weeks in this study.

Older patients have lower survival rates, which could be connected to not receiving therapy at the same rate as younger patients, study authors reported. Hypofractionated RT could benefit these patients because it would provide them with well-tolerated RT over a shorter timeline.

“Providing a therapy that is tolerable in this population may reduce this age disparity in survival outcomes, although it remains to be seen whether the increased potency of hypofractionated RT approaches the potency regimens of concurrent chemoradiation for controlling locally advanced disease,” study authors said.

Timmerman said a larger trial comparing these results to standard combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy is needed.

“We have already instigated a larger, randomized trial to compare the new 15 treatment regimen to conventional radiation using 30 treatments,” he said. “Depending on the results, a trial comparing the new high-tech, yet cost-effective, therapy to standard chemo-radiotherapy in better performing patients should be considered.”

For more information: www.redjournal.org

September 12, 2024

September 12, 2024