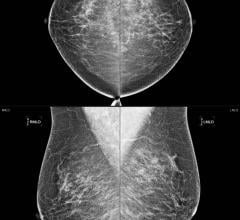

September 22, 2014 — Randomized trials from the 1970s and 80s suggested that mammography screening prevents deaths from breast cancer. But the methods used by some of these studies have been criticized, and this has raised doubts about the validity of the findings. Advances in technology and treatment have also led to questions about the reliability of older trials to estimate the benefits and harms of modern day screening.

So, researchers in Norway set out to evaluate the effectiveness of modern mammography screening by comparing the effects on breast cancer mortality among screened and unscreened women.

They analyzed data from all women in Norway aged 50 to 79 between 1986 and 2009 — the period during which the Norwegian mammography screening program was gradually implemented. They compared deaths from breast cancer among women who were invited to screening with those who were not invited, making a clear distinction between cases of breast cancer diagnosed before (without potential for screening effect) and after (with potential for screening effect) the first invitation for screening.

They also used a simulation model to estimate how many women aged 50-69 years would need to be invited to screening every two years to prevent one breast cancer death during their lifetime.

Based on more than 15 million person years of observation, breast cancer deaths occurred in 1,175 of the women invited to screening and in 8,996 of the women who were not invited.

After adjusting for factors such as age, area of residence and underlying trends in breast cancer mortality, the researchers estimate that invitation to mammography screening was associated with a 28 percent reduced risk of death from breast cancer compared with not being invited to screening. The screening effect persisted, but gradually declined with time after invitations to screening ended at 70 years of age.

Using the simulation model, they also estimate that 368 women aged 50-69 would need to be invited to screening every two years to prevent one death from breast cancer during their lifetime. Further analysis to test the strength of the findings did not substantially change the results.

"In our study, the estimated benefit for breast cancer mortality (28 percent) associated with invitation to mammography screening indicates a substantial effect," say the authors. But evolving improvements in treatment "will probably lead to a gradual reduction in the absolute benefit of screening," they conclude.

This study "adds important information to a growing body of observational evidence estimating the benefits and harms of screening," say U.S. researchers in an accompanying editorial, and should "make us reflect on how to monitor the changing benefits and harms of breast cancer screening." They call for women to be given balanced information to help them make informed decisions about screening.

For more information: www.bmj.com/content/348/bmj.g3701

July 29, 2024

July 29, 2024