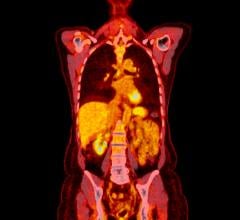

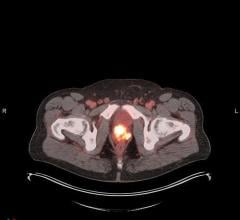

August 19, 2016 — A new non-invasive positron emission tomography (PET) technique can obtain images of neuron proliferation in an area of the brain known to be particularly affected by depression. Scientists from the RIKEN Center for Life Science Technology (CLST) in Japan used the technique to observe this process, known as neurogenesis, in the subventricular zone and subgranular zone of the hippocampal dentate gyrus.

These two areas are known to be neurogenic regions, where neural stem cells give rise to new neurons throughout our lives. Hippocampal neurogenesis is known to be associated with depression and the effect of antidepressive medication, but it is also involved in learning and memory, so scientists are keen to find techniques that can monitor cell proliferation in the region. However, the process of neurogenesis is very hard to monitor non-invasively. It is possible using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), but with MRI the tracers do not move into the brain effectively and must be injected directly into the brain fluid, making is invasive and difficult to perform.

PET is another method that has been used. Previously, attempts have been made to use a molecule called [18F]FLT as a marker for cell proliferation in the brain in PET, but unfortunately the difference in signal strength between regions with and without cell growth was small. "We were not exactly sure why this was happening," said Tamura, "but surmised that it is because the body actively pumps the molecule out of the brain through the blood-brain barrier, using active transport mechanisms. This means that it is difficult for [18F]FLT to accumulate in the brain in sufficient concentrations to allow effective imaging."

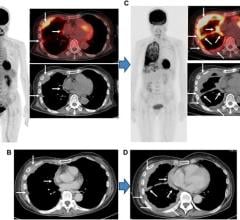

To test whether this was the case, they tried injecting rats with a drug called probenecid, which is known to inhibit the active transport of molecules like [18F]FLT outside of the brain. They were happy to see that the strategy worked. They found clear signals of neurogenesis in the two areas of the adult brain, and these signals were significantly decreased in the hippocampal dentate gyrus of rats that had been treated with corticosterone to trigger depression. When the rats were treated with an anti-depressive selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, the amount of cell proliferation was shown to increase, demonstrating that the drugs were countering the loss of neurogenesis caused by the corticosterone.

According to Yosky Kataoka, M.D., Ph.D., who led the research team, "This is a very interesting finding, because it has been a longtime dream to find a non-invasive test that can give objective evidence of depression and simultaneously show whether drugs are working in a given patient. We have shown that it is possible, at least in experimental animals, to use PET to show the presence of depression and the effectiveness of drugs. Since it is known that these same brain regions are involved in depression in the human brain, we would like to try this technique in the clinic and see whether it turns out to be effective in humans as well."

For more information: www.riken.jp/en

July 30, 2024

July 30, 2024