December 8, 2014 — A study presented at the annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) investigated a new device that may result in more comfortable mammography for women. According to the study, standardizing the pressure applied in mammography would reduce pain associated with breast compression without sacrificing image quality.

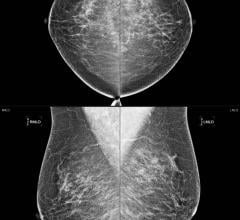

Compression of the breast is necessary in mammography to optimize image quality and minimize absorbed radiation dose. However, mechanical compression of the breast in mammography often causes discomfort and pain and deters some women from mammography screening.

An additional problem associated with compression is the variation that occurs when the technologist adjusts compression force to breast size, composition, skin tautness and pain tolerance. Over-compression is common in certain European countries, especially for women with small breasts; under-compression is more common in the United States.

“This means that the breast may be almost not compressed at all, which increases the risks of image quality degradation and extra radiation dose,” said Woutjan Branderhorst, Ph.D., researcher in the department of biomedical engineering and physics at the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam.

Overall, adjustments in force can lead to substantial variation in the amount of pressure applied to the breast, ranging from less than 3 kilopascals (kPa) to greater than 30 kPa.

Branderhorst and colleagues theorized that a compression protocol based on pressure rather than force would reduce the pain and variability associated with the current force-based compression protocol. Force is the total impact of one object on another, whereas pressure is the ratio of force to the area over which it is applied.

The researchers developed a device that displays the average pressure during compression and studied its effects in a double-blinded, randomized control trial on 433 asymptomatic women scheduled for screening mammography.

Three of the four compressions for each participant were standardized to a target force of 14 dekanewtons (daN). One randomly assigned compression was standardized to a target pressure of 10 kPa.

Participants scored pain on a numerical rating scale, and three experienced breast screening radiologists indicated which images required a retake. The 10 kPa pressure did not compromise radiation dose or image quality, and, on average, the women reported it to be less painful than the 14 daN force.

There are an estimated 39 million mammography exams performed every year in the United States alone, which translates into more than 156 million compressions. Pressure standardization could help avoid a large amount of unnecessary pain and optimize radiation dose without adversely affecting image quality or the proportion of required retakes.

The device that displays average pressure is easily added to existing mammography systems, according to Branderhorst.

“Essentially, what is needed is the measurement of the contact area with the breast, which then is combined with the measured applied force to determine the average pressure in the breast,” he said. “A relatively small upgrade of the compression paddle is sufficient.”

Further research will be needed to determine if the 10 kPa pressure is the optimal target.

For more information: www.radiologyinfo.org

July 29, 2024

July 29, 2024