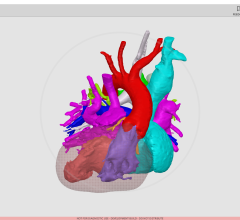

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more effective than electrocardiography (ECG) at identifying "silent" heart attacks, also known as unrecognized myocardial infarctions, according to a study performed by National Institutes of Health researchers and international colleagues. Overall, the study found that silent heart attacks are more frequent than previous studies have reported, particularly in certain populations such as older adults with diabetes. Silent heart attacks appear to be much more common than those with recognized symptoms. "Prevalence and Prognosis of Unrecognized Myocardial Infarction Determined by Cardiac Magnetic Resonance in Older Adults" was published Sept. 5 in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

The study involved 936 participants aged 67 to 93 years, enrolled in the Age Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study (AGES). Of the participants, 670 were randomly selected and 266 were selected because they were known to have diabetes. Because 71 of the randomly selected participants also had diabetes, the overall study population consisted of 337 people who had diabetes and 599 who did not.

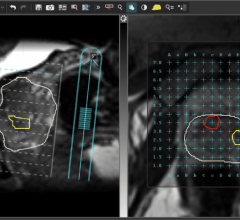

Cardiac MRI indicated that more participants, both with and without diabetes, had silent heart attacks (21 and 14 percent, respectively) than recognized heart attacks (11 and 9 percent, respectively). ECG was less effective, detecting silent heart attacks in only five percent of the participants in both groups. Silent heart attacks identified by cardiac MRI were associated with a higher risk of mortality during the study period, while silent heart attacks identified by ECG were not. However, participants who had either form of heart attack were significantly more likely to die than those who had neither.

The analysis also found that people with silent heart attacks displayed many cardiovascular risk factors associated with recognized heart attacks, such as high blood pressure and evidence of atherosclerosis (a disease in which plaque builds up inside the arteries). Yet, fewer study participants who had a silent heart attack were taking medications such as statins or aspirin compared with survivors of recognized heart attacks (36 vs. 73 percent).

The study authors suggest that people who may have an increased risk for silent heart attacks, such as older people with diabetes, may benefit from following cardiovascular disease prevention methods, given the high prevalence of silent heart attacks and their association with increased mortality.

This study was conducted by researchers at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Institute on Aging; and the Icelandic Heart Association.

For more information: www.nih.gov

July 25, 2024

July 25, 2024