July 11, 2014 — Breast cancer screening costs for Medicare patients skyrocketed between 2001 and 2009, but the increase did not lead to earlier detection of new breast cancer cases, according to a clinical study published by Yale School of Medicine researchers in the July 1 issue of the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

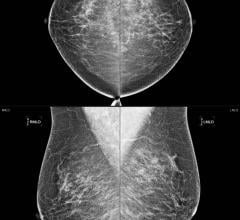

While the number of screening mammograms performed among Medicare patients remained stable during the same time period, the study focused on the adoption of newer imaging technologies in the Medicare population, such as digital mammography. Brigid Killelea, M.D., assistant professor of surgery, and Cary Gross, M.D., professor of internal medicine at Yale School of Medicine and director of the Cancer Outcomes, Public Policy, and Effectiveness Research (COPPER) Center at Yale Cancer Center, were lead authors of the study.

"Screening mammography is an important tool, but this rate of increase in cost is not sustainable," said Killelea, assistant professor of surgery. "We need to establish screening guidelines for older women that utilize technology appropriately, and minimize unnecessary biopsies and over-diagnosis to keep costs under control."

Gross, Killelea, and other members of the Yale COPPER research team explored trends in the cost of breast cancer screening. They identified the use of newer, more expensive approaches including digital mammography and computer aided detection (CAD), as well as the use of other treatment tools and subsequent procedures such as breast MRI and biopsy, between 2001-2002 and 2008-2009. They also assessed the change in breast cancer stage and incidence rates between the two time periods.

They found that use of screening mammography was similar between the time periods — at around 42 percent of female Medicare beneficiaries without a history of breast cancer. There was a large increase in the use of digital mammography technology, which is more expensive than standard film technology ($115 vs. $73 per mammogram) and has not been shown in clinical trials to be superior for women 65 years or older.

The team also found a considerable increase in the use of other newer, more expensive screening and related-adjunct technologies. As a result, Medicare spending for breast screening and related procedures increased from $666 million (in 2001-2002) to $962 million (2008-2009).

While the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force does not recommend breast cancer screening for women age 75 years and older, the COPPER team found that Medicare still spent an increasing amount per woman 75 years and older in the study.

"We need further studies to identify which women will benefit from screening, and how to screen effectively and efficiently," said Gross. "But we cannot simply adopt new technologies because they theoretically are superior — the health system cannot sustain it, and more importantly our patients deserve a sustained effort to determine which approaches to screening are effective and which ones are not. In some instances, breast cancer screening can save lives. But no woman wants to undergo testing if it is likely to cause more harm than good.

For more information: www.oxfordjournals.org/licensing/index.html?doi=10.1093/jnci/dju159

July 29, 2024

July 29, 2024