July 26, 2016 — A new study shows that patients with brain metastases can be treated in an effective and substantially less toxic way by omitting a widely used portion of radiation therapy. These results will allow tens of thousands of patients with this most common form of brain tumor to experience a better quality of life while maintaining the same length of life.

The study was accepted for publication by the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA).

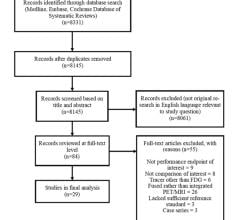

Anthony L. Asher, M.D., FACS, medical director at Carolinas HealthCare System's Neurosciences Institute and the senior author on the report, and Stuart H. Burri, M.D., chairman, department of radiation oncology at Levine Cancer Institute, began their research on this subject over 10 years ago in Charlotte, N.C. Along with Paul Brown, M.D., at Mayo Clinic, they spearheaded an international, multi-institutional, randomized trial that will ultimately improve the standard of care for patients with brain metastases by reducing the toxicity of their treatment without reducing the effectiveness.

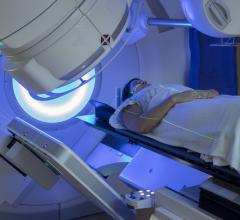

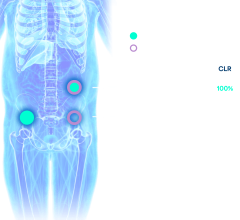

Typical therapies for these types of brain tumors include surgery, whole brain radiation therapy and focused radiation, also known as stereotactic radiosurgery. "We discovered that whole brain radiation added to focused radiation in the treatment of brain metastases — in other words, cancer that travels to the brain — reduces the number of new brain tumors over time; however, patients receiving the whole brain radiation had significantly more difficulties with memory and complex thinking than patients who only had the focused radiation," said Asher.

"Whole brain radiation patients also reported worse quality of life compared with patients who only received the focused radiation," added Burri. "Interestingly, the data showed that the addition of whole brain radiation produced no improvement in survival."

According to the American Cancer Society, in 2016, there will be approximately 1.7 million new cancer cases diagnosed in the United States. Almost one in four of those patients (about 400,000) will experience spread of their cancers to the brain. In contrast, 300,000 and 240,000 patients will be newly diagnosed with breast and primary lung cancers, respectively, each year. "Brain metastases are not only extremely common, they are also a major source of disability in society," said Asher. Because of their location, these tumors often produce severe neurological symptoms, such as headaches, weakness or problems with speech and information processing, thereby compromising both daily function and quality of life in cancer patients.

According to Asher, there are two primary objectives in cancer care: to improve survival, and to maintain or improve quality of life for patients.

"In the past, clinicians who treated patients with brain tumors seldom used sophisticated techniques like neurocognitive tests to evaluate patients' daily function in response to various therapies," said Burri. "Without those tests, we might have incorrectly concluded that whole brain radiation was a better option for patients because it made their scans look better, at least in the short term. However, the data from our study shows that clinicians can no longer simply rely on the results of traditional lab tests or scans to assess the value of care; we have to understand the total impact of cancer therapies on our patients."

Asher and Burri emphasize that the real importance of this study is its potential to make us think differently about what really matters in cancer therapy.

The trial authors concluded that the benefit of adding whole brain radiation was outweighed by its risks in patients with one to three newly diagnosed brain metastases. This is a very relevant finding, as over 200,000 patients still receive whole brain radiation in the United States each year, and the majority of patients with brain metastases have a limited number (typically three or less) of brain lesions. Asher and Burri, along with their co-investigators, now recommend that patients with one to three brain metastases should no longer receive routine whole brain radiation therapy, and should be treated with focused therapy alone to better preserve cognitive function and quality of life.

They are now working on a new method of focused therapy for tumors that have spread to the brain that combines radiation and surgery. The technique was pioneered at Levine Cancer Institute and they are looking to expand and further validate the approach with the National Cancer Institute.

For more information: www.jama.jamanetwork.com

August 09, 2024

August 09, 2024