July 30, 2014 — Information hidden in imaging tests could help doctors more accurately choose the radiation therapy dose needed to kill tumors, suggests a study of more than 300 cancer patients presented at the 56th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM).

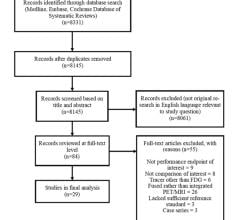

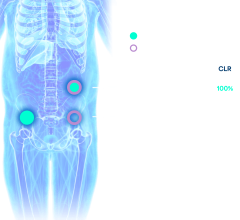

The research is the largest study to date to use radiomics — extracting statistical information from images and other measurements — to help predict the likely progression of cancer or its response to treatment based on positron emission tomography (PET) scans of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and head and neck cancer.

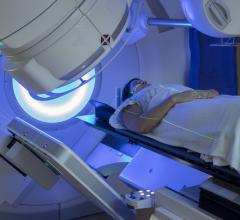

“Currently, there is a one-size-fits-all process for selecting radiation therapy doses, which might be too much for some patients and not enough for others,” said Joseph Deasy, Ph.D., senior author of the study and chair of the department of medical physics at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York. “Radiomics will help us know when we can turn down the treatment intensity with confidence, knowing we can still control the disease.”

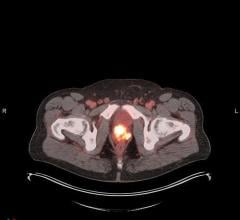

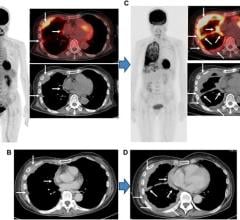

In the study, researchers performed positron emission tomography (PET) scans in 163 non-small cell lung cancer patients and 174 head and neck cancer patients before and after treatment. They extracted a variety of information from each tumor, including the intensity value of the PET image, the roughness of the image and other information, such as how round the tumor was. In PET, the brighter an area is, the higher the intensity, showing that the tumor is consuming a greater amount of energy from the injected radioactive glucose substitute tracer.

Comparing the information gleaned from the before and after scans to how the patient fared — including whether the tumor shrank or how long the patient survived — researchers can create models that will help direct future therapy. For example, in the study researchers determined that lung tumors that have a higher uptake of the tracer need to be treated with a higher dose of radiation than is typically prescribed.

“Standard protocol today is to only use PET imaging to define the extent of a tumor to be treated,” said Deasy. “Based on the information from this study, the data would be extracted from those images and put into models that would tell the physician what dose was required to kill the tumor with a high probability.”

He noted that radiomics is a team effort that requires good collaboration between physicians, physicists and computer scientists.

In addition to Deasy, collaborators on the study are: J. Oh, H. Veeraraghavan, A. Apte, A. Rimner, M. Folkert, N. Lee, Z. Kohutek, H. Schoeder, M. Dunphy, J. Humm and S. Nehmeh.

For more information: www.aapm.org

August 09, 2024

August 09, 2024