Photo courtesy of Carestream

Women with a history of a false-positive mammogram result may be at increased risk of developing breast cancer for up to 10 years after the false-positive result, according to a study led by a researcher with the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

The study was published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

“Our finding that breast cancer risk remains elevated up to 10 years after the false-positive result suggests that the radiologist observed suspicious findings on mammograms that are a marker of future cancer risk,” said the study’s lead author, Louise M. Henderson, Ph.D., a UNC Lineberger member and an assistant professor of radiology at the UNC School of Medicine in Chapel Hill. “Given that the initial result is a false-positive, it is possible that the abnormal pattern, while noncancerous, is a radiographic marker associated with subsequent cancer.”

In the United States, 67 percent of women ages 40 and older undergo screening mammography every one to two years, Henderson said. Prior studies have shown that about 16 percent of first mammograms and 10 percent of subsequent mammograms will generate a false-positive result.

During the course of 10 screening mammograms, the chance of at least one false-positive result is 61 percent for women screened annually, and 42 percent for women screened every two years, Henderson said.

For this study, Henderson and colleagues analyzed data from the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium (BCSC) from 1994 to 2009. The study population, which came from seven registries in different parts of the United States, included 2.2 million screening mammograms performed in 1.3 million women, ages 40 to 74 years. The Carolina Mammography Registry, a registry that draws on data from imaging facilities across North Carolina and housed at UNC-Chapel Hill, was one of the seven registries included in the study.

After the initial screening, women in the study were tracked across 10 years. During this period, 48,735 women were diagnosed with breast cancer.

After a mammogram, women showing some evidence of suspicious tissue will typically be referred for additional imaging, and some of those women will be further referred for a breast biopsy, Henderson explained. After adjusting for common factors that influence breast cancer risk, Henderson and colleagues found in their study that women whose mammograms were classified as false-positive who were referred for additional imaging had a 39 percent increased chance of developing subsequent breast cancer during the 10-year follow-up period, compared with women with a true-negative result. Women whose mammograms were classified as false-positive but were referred for a breast biopsy had a 76 percent increased chance of developing subsequent breast cancer compared with women with a true-negative result.

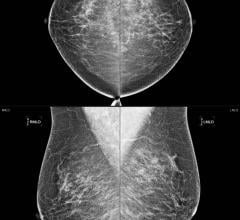

Henderson also examined whether breast density affected the relationship between false-positive mammograms and subsequent breast cancer, using the BI-RADS breast density categories of almost entirely fat, scattered fibroglandular densities, heterogeneously dense, and extremely dense.

“A higher proportion of false-positive results were present among women with heterogeneously or extremely dense breasts compared with women who had almost entirely fatty breasts or scattered fibroglandular densities,” Henderson said. This was not surprising, as increased breast density is known to make mammograms more difficult to read, she said.

Breast density did not affect the relationship between false-positive mammograms and subsequent cancer for most women.

Recent research has shown that women who experience false-positive mammograms tend to feel anxious and may develop negative effects on behavior and sleep. Henderson said she does not want the study findings to increase anxiety over mammograms and breast health because the increase in absolute risk with a false positive mammogram result is modest.

“We don’t want women to read this and feel worried,” she said. “We intend for our findings to be a useful tool in the context of other risk factors and assessing overall breast cancer risk.”

Age, race, family history of breast cancer, history of a breast biopsy, and mammographic breast density are also significant factors in determining a woman’s risk in the BCSC risk calculator, Henderson said.

“Our next steps are to consider how to incorporate a prior false-positive mammogram and biopsy results into risk-prediction models for breast cancer,” she said.

Henderson, who is also an adjunct assistant professor in the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health, noted that results from this study are consistent with findings from several other countries, including Denmark, Spain and the United Kingdom. The primary limitation of the study is that women may have moved out of the registry areas while the study was being conducted, in which case they were no longer followed. The researchers also could not assess how many cancers developed from the site of the initial suspicious mammographic finding and how many were missed cancers from a different location, including the other breast.

The study was funded by the BCSC and grants from the National Cancer Institute. Henderson declares no conflicts of interest.

In addition to Henderson, other authors on the study include: Rebecca A. Hubbard of the Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania; Brian L. Sprague of the Department of Surgery and Office of Health Promotion Research at the University of Vermont; Weiwei Zhu of the Group Health Research Institute in Seattle; and Karla Kerlikowske of the Departments of Medicine and Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco, and of the UCSF Department of Veterans Affairs General Internal Medicine Section.

For more information: www.aacr.org

July 29, 2024

July 29, 2024