November 3, 2009 – By relying solely on a patient’s clinical risk profile or the results of one imaging test when assessing patients with chest pain, physicians may be missing important, early signs of atherosclerotic disease and opportunities to intervene, according to new findings published in the Nov. 10, 2009 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC).

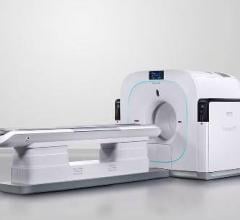

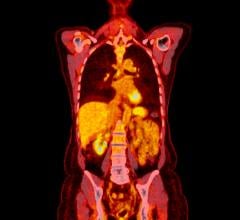

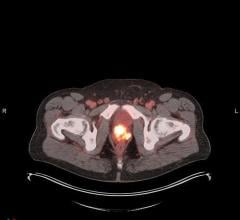

The authors recommend adding coronary artery calcium score (CACS) testing in patients with a normal single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scan to better identify those at high long-term risk for cardiac events, in whom an earlier focus on aggressive risk factor modification and other medical therapies may be beneficial.

“Typically, when a patient presents with chest pain and the [SPECT] test result is normal, we tell them everything looks fine, but this may not be the case,” said John Mahmarian, M.D., a cardiologist in Houston, and principal investigator of the study. “If a large extent of calcium is present in the coronary arteries, which can’t be measured by functional SPECT imaging, he or she is at high long-term risk for a cardiac event. Based on our findings, using both tests to define risk is better than either test alone.”

The study – the first to be conducted over such a long duration – found that approximately half of all patients with a normal SPECT result had a CACS of at least moderate severity, signaling cardiac risk that would not otherwise have been predicted. Increasing CACS severity is associated with a greater likelihood of cardiac events and deaths. Alarmingly, the risk of death or a heart attack over time increased by threefold when the calcium score was severe in patients with a normal SPECT. CACS was also found to be a stronger predictor of cardiac events than diabetes, which is considered synonymous with having coronary artery disease.

For this reason, authors urge CACS be performed in patients with a normal SPECT who have an intermediate or high clinical risk factor profile for coronary artery disease (e.g., smoking, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, diabetes, family history). If CACS is high, patients should be treated aggressively to prevent the progression of disease, adds Dr. Mahmarian.

“Although a normal SPECT result predicts excellent short-term event-free survival, it doesn’t tell us anything about long-term risk, and long-term outcome is significantly worse if the CACS is severe,” said Dr. Mahmarian. “By integrating these two tests, we can identify patients at high long-term risk for heart problems and may, thereby, have a better shot at preventing further development of obstructive disease and improving outcomes.”

Investigators followed 1,126 asymptomatic patients without a previous history of coronary artery disease who had a CACS and stress SPECT scan performed within a close period of time (median of 56 days). The study period was from December 1995 to May 2006.

“Our results reinforce the need to press forward and look at how an integrated approach to imaging can be cost-effective in preventing downstream events and improving outcomes,” said Dr. Mahmarian.

The authors say the next step is to conduct prospective trials to evaluate how adding CACS to functional SPECT scans can guide the intensity of therapy targeted to individual patients and whether such an approach can improve outcome in a cost-effective manner.

For more information: www.acc.org

July 30, 2024

July 30, 2024