A 3-D model of a patient’s skull helped doctors prepare for surgery to remove a rare, high-stage tumor. Image courtesy of University of Michigan Health System.

April 6, 2016 — Doctors at the University of Michigan’s C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital recently used 3-D printing to create a replica of a 15-year-old patient’s skull to determine how to remove a rare type of tumor.

What started as a stuffy-nose and mild cold symptoms for Parker Turchan led to a far more serious diagnosis: a tumor in his nose and sinuses that extended through his skull near his brain.

“He had always been a healthy kid, so we never imagined he had a tumor,” said Parker’s father, Karl. “We didn’t even know you could get a tumor in the back of your nose.”

The Portage, Mich. high-school sophomore was referred to Mott, where doctors determined the tumor extended so deep that it was beyond what regular endoscopy could see.

The team needed to get the best representation of the tumor’s extent to ensure that their surgical approach could successfully remove the entire mass.

“Parker had an uncommon, large, high-stage tumor in a very challenging area,” said Mott pediatric head and neck surgeon David Zopf, M.D. “The tumor’s location and size had me question whether a minimally invasive approach would allow us to remove the tumor completely.”

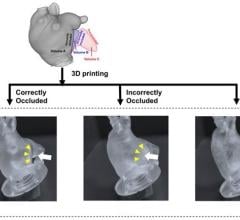

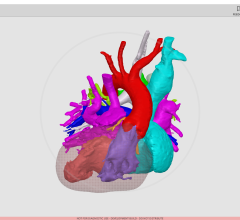

To help answer that question, teams at Mott crafted a 3-D replica of Parker’s skull.

The model, made of polylactic acid, helped simulate the forthcoming operation on Parker by giving U-M surgeons “an exact replica of his craniofacial anatomy and a way to essentially touch the ‘tumor’ with our hands ahead of time,” Zopf said.

Just as important, it also allowed the team to counsel Parker and his family by offering them a look at what lurked within — and, with the test run successfully complete, what would lie ahead.

The rare and aggressive tumor in Parker’s nose is known as juvenile nasopharyngeal angiofibroma, a mass that grows in the back of the nasal cavity and predominantly affects young male teens. Mott sees a handful of cases each year.

In Parker’s case, the tumor had two large parts: one roughly the size of an egg and the other the size of a kiwi. The mass sat right in the center of the craniofacial skeleton below the brain and next to the nerves that control eye movement and vision.

“We were obviously concerned about the risks involved in this kind of procedure, which we knew could lead to a lot of blood loss and was sensitive because it was so close to the nerves in his face,” said Karl, who nonetheless praised the 3-D methodology used to aid his son.

“It was pretty impressive to see the model of Parker’s skull ahead of the surgery. We had no idea this was even possible.”

Zopf, working with Erin McKean, M.D., a U-M skull base surgeon, was able to completely remove the large tumor. Kyle VanKoevering, M.D., and Sajad Arabnejad, M.D., aided in model preparation.

Through preoperative embolization, the blood supply to the tumor was blocked off the day before surgery to decrease blood loss. A large portion of the tumor was then detached endoscopically and removed through the mouth. The remaining mass under the brain was taken out through the nose.

Doctors took pictures of Parker’s anatomy during the surgery and, later, compared it to pictures from the model. They were nearly identical.

"Words alone can't express how thankful we are for Parker's talented team of surgeons at Mott,” said his mother, Heidi. “Parker is back to his old self again.”

Although medical application of the technology continues to gain attention, it isn’t entirely new. Zopf and Mott teams have used 3-D printing for almost five years.

3-D printed splints made at U-M have helped save the lives of babies with severe tracheobronchomalacia, which causes the windpipe to periodically collapse and prevents normal breathing. Mott has also used 3-D printing on a fetus to plan for a potentially complicated birth.

“We are finding more and more uses for 3-D printing in medicine,” Zopf said. “It is proving to be a powerful tool that will allow for enhanced patient care.”

Based on prior success in patients such as Parker and a continued collaborative effort, it’s a concept that appears poised to thrive.

“Because of the team approach we’ve established at the University of Michigan between otolaryngology and biomedical engineering, the printed models can be designed and rapidly produced at a very low cost,” Zopf said. “Michigan is one of only a few places in the nation and world that has the capacity to do this.”

For more information: www.mottchildren.org

June 25, 2024

June 25, 2024