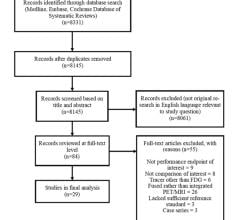

As a result of routine mammography screening, approximately 1.6 million breast biopsies are performed annually to determine whether a suspicious lesion is malignant or benign. Of these 1.6 million biopsies, approximately 20 percent will result in a positive cancer diagnosis.[1] These numbers are staggering alone, and are just the statistics for one out of more than 200 types of cancers. As radiologists, we strive to provide our patients with the best medical care available, but what we do not always think about is what happens after a sample leaves our office. Errors that occur in the biopsy diagnostic process are specific diagnostic errors that imaging professionals must address.

A Complex Process

Imaging professionals are often one of the first points of contact for patients during the biopsy process, but certainly are not the last. Within the biopsy process the most common errors involve the specimen being mislabeled or contaminated during the routine biopsy evaluation process. These potential errors are referred to as specimen provenance complications (SPCs). However, the possibility for human error is present at every stage of this process, especially since several different people are involved and many steps take place in separate locations.

After biopsy sample is taken, the tissue sample moves through a complex 18-step process, no matter if an internal or reference lab is used. In the pre-analytic phase, specimens are collected, labeled, transported and accessioned into the pathology lab. The next step is the analytic phase, where the specimens are examined grossly, dissected and prepared for analysis. This involves placing them into cassettes, which are then processed through a chemical bath that produces a final wax tissue block. A small cut of tissue from the block is then placed on a slide. Finally, in the post analytic phase, the slides are delivered to the pathologist for review, along with the accompanying paperwork for each patient.

Given the complex nature of the diagnostic testing cycle, and the potentially devastating ramifications of incorrect diagnosis, preventing diagnostic mistakes due to SPCs is crucial for the medical staff involved in the biopsy process and the patient.

How Often Does This Happen?

It is estimated that approximately 1 percent of all surgical biopsies are subject to undetected tissue transposition or contamination, which could lead to a cancer diagnosis being assigned to the wrong patient, ultimately leading to inappropriate or delayed treatment. These events not only result in harm to patients, but often have serious legal implications for the healthcare providers responsible for the error. Anecdotally, I have heard of several such instances from colleagues over the years.

DNA’s Role in the Evaluation Process

At Women’s Breast Center in Santa Monica, Calif., the Know Error system is used for breast biopsies, which has added minimal disruption to the practice’s standard processes. At the time of the biopsy procedure, a buccal swab of the patient’s cheek is taken to obtain a DNA reference sample. Then the swab is sent to an independent DNA laboratory. The biopsy tissue samples are collected as usual, then placed in bar-coded specimen containers matching that of the buccal swab, and sent to the pathology lab for evaluation. If a malignancy is found in a biopsy sample, a DNA specimen provenance assignment (DSPA) test is completed to compare the DNA profiles of the biopsy tissue and DNA reference sample. Concurrence of these profiles allows for absolute confirmation of patient identity, and is imperative before any diagnosis or treatment course is rendered. Since implementing the DSPA program, our staff has helped ensure that the many women who receive biopsies at our practice are getting the most accurate information possible.

Adding this DNA confirmation — or taking a DNA timeout — completes the diagnostic testing cycle and protects radiologists and patients alike.

Moreover, the power of DNA confirmation reduces unnecessary medical errors and helps fulfill the promise we provide to our patients who entrust us with their care. itn

Gregory Eckel, M.D., is the chief of breast intervention at Harbor UCLA Medical Center, an associate clinical professor of radiology at UCLA, and a clinical breast radiologist at the Women’s Breast Center in Santa Monica, Calif.

Reference

1. Silverstein, M.J., et al. “Image-detected breast cancer: State of the art diagnosis and treatment. “ J Am Coll Surg 2005; 201(4), 586-597.

July 31, 2024

July 31, 2024