Image courtesy of Medic Vision

While working with a patient with Crohn’s disease in my gastroenterology practice, I nearly ordered a computed tomography (CT) scan for her as I began to formulate a plan. After talking with her, I discovered she had received 18 CT scans at multiple hospitals in the prior three years. As a physics major, I knew medical radiation was potentially harmful, but nowhere was that harm calculated and put into real terms for me to assimilate in my plan. I spent about four hours over the next few days computing the radiation from the various studies, only to find that this patient had more than two-and-a-half times the equivalent radiation dose of standing one mile from the atomic bomb blast at Hiroshima. On the back of my business card, I wrote the estimated effective radiation dose and the potential incremental cancer risk to her, telling her to show it to physicians in the future if someone thought a nineteenth scan may be useful. In the years since, she has not had another CT. That case and other anecdotal experiences have convinced me that physicians would be more thoughtful about their imaging decisions if they were more aware of the potential human consequences of their decisions. We are so vigilant about our imaging decisions with children; why not adults?

Not every patient will be able to avoid another radiological exam and many will need them. But issues with overutilization are not a secret, as studies from the last decade indicate 20 to 50 percent of high-tech imaging procedures may be be unnecessary. This is due partly to “defensive medicine,” but also from a false sense of security physicians may have from imaging results. In order to help ordering physicians be more judicious in requesting radiological exams, information on the history of exposure and on potential exposure to radiation needs to be easily accessible and easily understood — a responsibility radiologists or digital health technology are best equipped to bear.

This begs an important question in the radiology community on radiation exposure and its dangers: Is it better to have some form of metrically driven data or none at all because the data isn’t a perfect science? Why store the cumulative radiation exposure data in systems, but not reveal them to ordering clinicians, much less patients?

Factors Contributing to Complications

The American College of Radiology (ACR) has recognized the value in alerting physicians appropriately about levels of radiation. However, there are two challenges with the system we have in place to communicate this data from radiologist to physician: terminology and analysis.

Radiation exposure terminology is not well understood by the average physician. To circumvent that, a radiation symbol scale was created, but delivers no real value. No physician can understand the real difference between one radiation symbol on the scale and two radiation symbols, much less three. Even if the symbols represent a range the impact is lost because symbols hide data. The cumulative effect of radiation is now being tallied by the machines, but this information does little for the ordering clinician if it’s not revealed and explained.

Though it is mandated for radiologists to note radiation in reports, there is a gap in analysis of radiological data as well. The computed tomography dose index (CTDI) is reported from the CT scan, the report is put into the electronic health record (EHR), and that’s as far as the data makes it. There is much more potential for this data to be used with other patient data for analysis, providing a more complete picture of the patient’s past exposure.

The Conversation About Cost

The other consideration for curbing overutilization is that imaging is expensive to our health system. As tests are being overutilized, insurance decreases reimbursement to radiologists and to health systems, which hardly seems fair. It is not the radiologist’s fault. Physicians need and want cost transparency in all areas of treatment. A survey from Deloitte University discovered cost is a part of the information puzzle physicians find most valuable, but have the least access to. Looking at seven types of data, physicians considered cost data the third most important behind clinical outcomes and patient experience, yet it is the least available out of all of the data. While the physician orders the exam, understanding the impact of cost is important for driving a mentality of clinical stewardship within the healthcare system, including radiology.

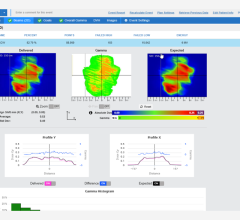

This mentality has taken off at a number of hospitals across the country through the deployment of technology that brings cost and risk data in front of providers at the point of care. This is not an obtrusive decision support system, which can become a source of frustration for end users because of an inordinate number of clicks to execute a radiographic order. Rather, this is a presentation of defined non-EHR metrics that influence and curb unnecessary imaging, but allow physician autonomy. Hospitals are deploying an EHR-agnostic, patent-pending Smart Ribbon of information that alerts providers to risks, costs, and alternatives on medications, labs and radiology without disrupting workflow. Both the Texas and Georgia Hospital Associations have been pioneers of this technology. Data from 50 hospitals in Texas has shown a 5.6 percent reduction in inpatient imaging tests as a result of the technology’s deployment. This technology demonstrates the potential of a collaborative relationship between radiology and ordering physicians, where cost and risk is not only measured and tracked, but properly communicated to the physician. There currently is no obtrusive clinical decision support system that can replicate the “next best radiographic test” advice that a human radiologist can impart. So why not call and collaborate with the radiologist in the imaging suite that day?

A Collaborative Future

Overall, physicians and radiologists seem to be on the same page about the overutilization of imaging. Workflow is a challenge, yet collaboration — finding a more seamless way for both parties to communicate with each other — is key for appropriate use of imaging. Some of this future lies in changes to coding and compensation for radiologists. As doctors, even interventional radiologists are able to document and charge for encounters. Why can’t a radiologist charge for a “consult” where the labs are reviewed, notes are reviewed and a physician says, “I think my patient has cirrhosis given his jaundice, low platelet count and varices, but his CT is normal; what’s the next best imaging test if he can’t have an MRI?”

Patients rely on the healthcare system as a whole to guide them as to what is in their best interest. They may mistakenly perceive an additional radiology exam to mean a provider is being more thorough. Unfortunately, the patient does not understand an “iatrogenic risk” or a “therapeutic cascade.” They also don’t understand how siloed portions of their care may actually be, assuming that various specialists communicate and collaborate more than they really do. It is the job of the ordering physician to make value judgments on care. To do so, physicians need the support and help of radiology counterparts that seek to enlighten them about exposure and risk. This level of collaboration is a win-win for radiologists, doctors and most importantly, patients. Current EHRs and third-party decision support systems have not gotten us much closer. Presenting cost, iatrogenic risks and incentivizing clinician-radiologist collaboration preserve physician autonomy, gratification and will reduce unnecessary testing.

Mukul Mehra, M.D., is the CMO and co-founder of IllumiCare and practicing gastroenterologist in Birmingham, Ala.

August 09, 2024

August 09, 2024