Watson avatar courtesy of IBM

Artificial intelligence (AI) may soon be routine in radiology. It won’t take the shape of robots that clank and whir. Or animated heads of the Max Headroom variety. Or disembodied voices à la HAL 9000.

No, it will be out of sight — and possibly out of mind — helping radiologists do their jobs, day in and day out.

Teleradiology provider vRAD is experimenting with a smart algorithm that will serve as a traffic cop for its picture archiving and communication system (PACS), directing computed tomography (CT) brain images that show early signs of intracranial bleeding to the tops of radiologists’ worklists. IBM/Merge’s Watson Health is being groomed to do much the same.

One version of the Watson platform for medicine would provide a kind of radiological triage that moves cases up and down, depending on patient needs. As with the vRAD software, brain bleeds would elbow their way to the top of worklists, boosted there by a filter that recognizes patterns associated with intracranial hemorrhage.

Both companies say their versions of this software could be operating later this year. Whether that happens will depend on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Minnesota-based vRAD is now preparing an FDA application with this worklist-adjusting algorithm presented to regulators as an extension of its already FDA-cleared PACS. The algorithm’s patent filing will provide the basis for the application, said Shannon Werb, vRAD chief information officer.

IBM/Merge has not publicly disclosed how it might approach the FDA with its AI technology. Steven Tolle, IBM/Merge chief strategy officer and president of

iConnect Network Services, told me, however, the training that goes into developing the AI software will lay the groundwork for its eventual regulatory submission, as will customer feedback on its design and performance.

Both executives have said emphatically that they are developing AI in the best interests of radiologists and patients. And neither is planning nor expects to make their AI programs competitive with the human practice of medicine. On that, they are adamant.

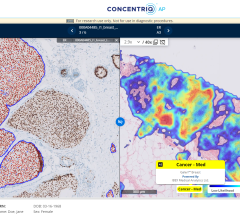

But IBM/Merge has ambitious plans, ones that could delegate to an intelligent machine some tasks that today only physicians are trained to perform. Watson might one day identify cancers in medical images, draw radiologists’ attention to suspicious masses by outlining them, and make the measurements that can help determine the effect of therapy or recurrence of disease. Watson might even “suggest,” as Tolle said, possible diagnoses.

Radiologists would have to sign off on those measurements before they become a permanent part of the radiology report. And Watson’s suggestions would be just that, he said … suggestions.

“We want to provide options for the physician to consider,” he said, stressing that Watson definitely would not render diagnoses.

Potentially in the nearer term is an application that radiologists would likely have few reservations about, if Watson’s performance lives up to expectations — an AI-enabled program that summarizes EMR information relevant to the interpretation of a patient’s images.

This application could find and summarize patient demographics, history and laboratory results, presenting these along with images from the patient’s prior exams.

“Where treating physicians may have more time to go in and out of an EMR to look for specific things that they want to find, radiologists really need to have at their fingertips an EMR summary of what is relevant to the image they are reading, as well as access to prior images,” he said. “We are leveraging technologies so that radiologists who are looking at an image can have the context in which to make their interpretations.”

Similarly near term is an effort by IBM to provide AI-enabled “audit services” that would look for tasks that need to be done. This AI-enabled diagnostic workstation might see in a radiology report the recommendation for a six-month follow-up. Watson would make sure that somebody schedules that follow-up, Tolle said.

IBM plans to implement this audit service for high-morbidity/mortality diseases — top priorities are cardiovascular disease; cancers of the breast, skin and lung; and COPD — as well as diseases that impose high costs of care, such as diabetes and Alzheimer’s.

“We can’t do all diseases at once, so we have to focus on ones that allow a meaningful impact in the short term,” he said. “Lung cancer detection is a great example, because when a hospital misses a lung cancer and the patient is diagnosed too late, there are severe consequences to the patient and usually a lawsuit against the provider.”

Read the 2017 article “How Artificial Intelligence Will Change Medical Imaging.”

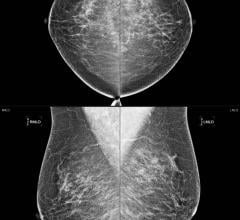

Watch the VIDEO “Examples of Artificial Intelligence in Medical Imaging Diagnostics.” This shows an example of how AI can assess mammography images.

Watch the VIDEO “Development of Artificial Intelligence to Aid Radiology,” an interview with Mark Michalski, M.D., director of the Center for Clinical Data Science at Massachusetts General Hospital, explaining the basis of artificial intelligence in radiology.

Greg Freiherr has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service The Freiherr Group. Read more of his views on his blog at www.itnonline.com.

Editor’s note: This column is the culmination of a series of four blogs by industry consultant Greg Freiherr on Working With Smart Machines. The blogs, “Will Artificial Intelligence Find a Home in PACS?,” “Watson, Come Here … Radiology Needs You,” “Promise and Pitfalls of Smart Machines” and “Beyond Diagnostics: Data Mining With AI,” can be found at www.itnonline.com/blogs.

August 29, 2024

August 29, 2024