The ongoing attacks directed against screening mammography remain a source of bitter disappointment for those of us who are focused on another war on a daily basis — that against a real killer known as breast cancer. We have a powerful weapon in the high-quality mammogram used as a screening method: We know this based on real science, stemming from the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted over the past 30 years that tested the impact of early detection on the breast cancer death rate.

The RCT is the most valid measure of the value of any test, and mammography screening has been measured by this method more than any other test in the history of medicine. The RCT works by evaluating an intervention (in this case, the mammogram) offered to a large group of randomly selected women (study group), and compares the outcome (in this case, death due to breast cancer) against a similar large randomized group not offered a mammogram (control group). The difference in death rates between the groups is then measured after a sufficiently long period of time, usually several years, to allow for a meaningful statistical analysis.

Swedish RCT

The largest RCT was conducted in Sweden between 1977 and 1985,1, 2 led by Laszlo Tabar, M.D., and Gunnar Fagerberg, M.D., and showed a 31 percent decrease in deaths from breast cancer among the women offered mammograms versus those who were not. The benefit was actually much greater than 31 percent, as the study group included 15 percent of women who chose not to accept the invitation to have a screening mammogram, and the control group included some who chose to obtain a mammogram outside the RCT. When this study and other studies evaluated the impact on those women who actually attended screening regularly, the decrease in mortality was 43 percent.3 Six other RCTs from the United States and Europe showed a similar benefit of decreased death rate in the groups offered screening mammography,4 all of which proved overwhelmingly supportive of all women receiving screening mammograms on a regular basis. The benefit of screening was demonstrated in every age group beginning at age 40. As a result, screening mammography began in earnest around the world.

Canadian Studies

There was a notable exception: the so-called “Canadian studies,” one for women 40-49, and the other for women 50-59, both of which showed no benefit to the women being offered mammography.5, 6 However, these studies have been criticized time and time again by the scientific community for unacceptable mammography quality and improper randomization: Any woman could volunteer to be included in the studies, and every woman was given a thorough physical examination by a trained examiner before being assigned to either the control group or the study group.7, 8 As a result, 80 percent of the advanced palpable cancers ended up in the study group, leading to a disproportionately large number of deaths in those women assigned to have mammograms, and essentially invalidating both studies. In fact, these studies were thrown out as true RCTs by the World Health Organization in 2000.9

Despite these and other serious flaws in the Canadian studies, it is these studies that individuals opposed to screening mammography have continually promoted as their “proof” that screening mammography does not work.10, 11, 12

Early Detection Saves Lives

The RCT data are the most powerful we have for measuring the value of a medical test, and the seven valid RCTs have proved beyond a doubt that early detection and treatment of breast cancer in an early stage results in a significantly lower death rate from the disease. Real-world validation can be found in the outcomes of the organized government-run mammography screening programs throughout the world, of which there are now more than 25.13 These have been operating on a large scale for many years as a result of the compelling findings of the RCTs, and have now involved more than 20 million women. The results of virtually every one of these programs showed a 30-50 percent decrease in breast cancer death.14

Again, the data are overwhelming that early detection through high quality screening mammography is making a difference, and that this benefit is appreciated in all age groups beginning at age 40.15, 16, 17 The explanation for this success: Screening cuts back on the rate of advanced, less controllable cancers.

However, those opposing early detection — largely pseudo-skeptics with no experience in screening — have stubbornly refused to acknowledge the huge benefits of screening mammography as demonstrated in the RCTs and the organized screening programs. Instead, they have focused on the so-called “harms” of mammography, most notably anxiety and overdiagnosis.10, 11, 12 Although it is true that there is always some transient anxiety associated with having a mammogram, the anxiety created by a far-advanced breast cancer in a woman who now faces death as a result of being advised not to obtain a screening mammogram would seem much greater; yet the opponents of screening focus only on the former. Moreover, the screening mammogram actually reduces anxiety for the 90 percent of women who have a normal mammogram. Thus, for the vast majority of women, the screening mammogram is a “good news” examination.

The Danish authors of the most recent attack on mammography screening12 focus on overdiagnosis, claiming that there is a large number of cancers detected by mammography that would never surface as a potential killing cancer in the woman’s lifetime. This issue has already been taken seriously by the scientific community and has been addressed in numerous peer-reviewed publications. All of these have shown that the demonstrated benefit of mammography in reducing the breast cancer death rate by 30-50 percent far outweighs the overdiagnosis (the claimed “harm”) that may exist in no more than1-5 percent of the cases.18 Strangely enough, the anti-screening campaign focusing on the harms of mammography originates in Denmark, a country with one of the highest breast cancer death rates in Europe. Fortunately, mammography screening has now started in Denmark as well, and shows a 25 percent decrease in breast cancer deaths.19

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) 2009 and 2016 recommendations20,21 also focused on the so-called “harms” of screening mammography, especially anxiety and overdiagnosis, as being greater that the benefit, i.e. preventing death from breast cancer. With virtually no valid data to support their claims of “harms,” they in essence made a value judgment rather than a scientific judgment. They also focused on the data from the “Canadian trials” and refused to consider the powerful collected data from the multiple organized screening programs from around the globe. The real irony of the above is that in 2014, the organized service screening programs involving 3 million women throughout Canada published their results, and showed at least a 40 percent reduction in breast cancer deaths among the screened women, including those in the 40-49 age group,16 a far cry from the results of the older “Canadian trials.”

Such results and other similar screening data failed to impress the USPSTF: In 2009 and again in 2016, they recommended no screening mammography for women of average risk in their 40s or above age 74, and mammograms every two years for women 50-74.20, 21 A recent study calculating the effect of complete compliance with these recommendations throughout the United States would result in 6,500 additional deaths from breast cancer, every year.22 Even more perturbing, these recommendations have the power of law under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), and would have become the guidelines for both government and private institutions, had Congress not passed a two year moratorium, allowing women to continue to have mammograms covered without a deductible yearly beginning at age 40.23 This moratorium is due to expire at the end of 2017, so there is still considerable concern that many women will lose affordable access to screening mammography under these terms.

Advances in Screening

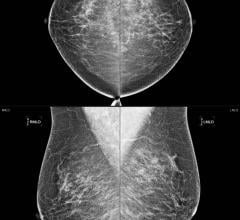

We know that mammography is not a perfect test — there is no perfect test in all of medicine. However, the RCTs and retrospective reviews measuring the effectiveness of screening mammography in the 1980s and 1990s fail to reflect the tremendous advances in breast cancer screening tests that have taken place since these older studies were conducted. We now have digital mammography, which has been shown to find more cancers than the older film screen images.24 And tomosynthesis, screening whole breast ultrasound and breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been shown to find another 20-40 percent more cancers than digital mammography alone.25, 26, 27 With prudent use of these tools, the effectiveness of screening in decreasing breast cancer deaths should soar even higher. Even so, the availability of screening mammography as our primary screening weapon must be maintained at this time. Without its continued widespread use, breast cancer death rates will surely rise. We know we have better tools on the way. As they become more affordable and more available, women will have an even greater chance of surviving and thriving, even in the face of this terrible disease.

Michael N. Linver, M.D., FACR, FSBI, is the director of mammography at X-Ray Associates of New Mexico, PC, and clinical professor of radiology at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine in Albuquerque, N.M.

References:

1. Tabar L, Fagerberg CJ, Gad A, et al. “Reduction in Mortality from Breast Cancer After Mass Screening with Mammography.” Randomised trial from the Breast Cancer Screening Working Group of the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare. Lancet. 1985;1(8433):829-32.

2. Tabar L, Vitak B, Chen TH, et al. “Swedish Two-county Trial: Impact of Mammographic Screening on Breast Cancer Mortality During 3 Decades.” Radiology. 2011;260(3):658-63.

3. Swedish Organized Service Screening Evaluation Group. “Reduction in Breast Cancer Mortality from Organized Service Screening with Mammography: 1. Further Confirmation with Extended Data.” Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(I1):45-51.

4. Smith RA, Duffy SW, Gabe R et al. “The Randomized Trials of Breast Cancer Screening: What have we learned?” Radiol Clin N Am. 2004;42:793-806.

5. Miller AB, Baines CJ, To T, et al. “Canadian National Breast Screening Study: 1. Breast Cancer Detection and Death Rates among Women aged 40 to 49 Years.” Can Med Assoc J. 1992;147:1459-76.

6. Miller AB, Baines CJ, To T, et al. “Canadian National Breast Screening Study: 1. Breast Cancer Detection and Death Rates among Women aged 50 to 59 Years.” Can Med Assoc J. 1992;147:1477-88.

7. Kopans DB, Feig SA. “The Canadian National Breast Screening Study: a Critical Review.” Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161:755-60.

8. Boyd NF. “The Review of the Randomization in the Canadian National Breast Screening Study. Is the Debate Over?” Can Med Assoc J. 1997;156:207-9.

9. IARC Handbook of Cancer Prevention. Vol 7, pp 100-102.

10. Gotzsche PC, Olsen O. “Is Screening for Breast Cancer with Mammography Justifiable?” Lancet. 2000;355(9198):129-134.

11. Welch HG, Proroc PC, O’Malley HJ et al. “Breast Cancer Tumor Size, Overdiagnosis, and Mammography Screening Effectiveness.” NEJM. 2016;375:1438-47.

12. Jorgensen KJ, Gotzsche PC, Kalager M et al. “Breast Cancer Screening in Denmark: A Cohort Study of Tumor Size and Overdiagnosis.” Ann Intern Med. January 10 2017; DOI:10.7326/P16-9129.

13. “Breast Cancer Screening Programs in 26 ICSN Countries, 2012: Organization, Policies, and Program Reach.” U.S. National Institutes of Health International Cancer Screening Network website. http://appliedresearch.cancer.gov/icsn/breast/screening.html. Accessed March 8, 2017.

14. Fitzgerald SP. “Breast-Cancer Screening — Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. N Engl J Med. 2015 Oct 8;373(15):1479. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1508733#SA3.

15. Nickson C, Mason KE, English DR et al. “Mammographic Screening and Breast Cancer Mortality: a Case-control Study and Meta-analysis.” Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012 Sep:21(0):1479-88.

16. Coldman A, Phillips N, Wilson C et al. “Pan-Canadian Study of Mammography Screening and Mortality from Breast Cancer.” J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014 Oct 1:106(11)

17. Gabe R, Duffy SW. “Evaluation of Service Screening Mammography in Practice: the Impact on Breast Cancer Mortality.” Ann Oncol. 2005;16 Suppl 2:153-62.

18. Duffy, SW, Olorunsola Agbaje, Tabar L, et al.: Overdiagnosis and overtreatment from two trials of mammographic screening for breast cancer. Br Ca Research Dec 2005 Vol 7, No 6 pp 258-265.

19. Christiansen P, Vejborg I, Kroman N, et al. “Position Paper: Breast Cancer Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment in Denmark.” Acta Oncol. 2014 Apr;53(4):433-44. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.874573. Epub 2014

20. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. “Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation Statement.” Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:716-26.

21. Siu AL; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. “Screening for Breast Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation Statement.” Ann Intern Med. 2016;164:279-96.

22. Hendrick RE, Helvie MA. “United States Preventive Services Task Force Screening Mammography Recommendations: Science Ignored.” Am J Roentgenol 2011;196:W112-W116.

23. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/3339. Accessed March 8, 2017.

24. Pisano ED, Gatsonis C, Hendrick E et al. “Diagnostic Performance of Digital Versus Film Mammography for Breast-Cancer Screening.” NEJM. 2005;353:1773-1783.

25. Friedewald SM, Rafferty EA, Rose SL et al. “Breast Cancer Screening Using Tomosynthesis in Combination with Digital Mammography.” JAMA. 2014:311(24):2499-2507.

26. Berg WA, Blume JD, Cormack JB. “Combined Screening with Ultrasound and Mammography versus Mammography Alone in Women with Elevated Risk of Breast Cancer.” JAMA. 2008;299(18):2151-2163.

27. Berg WA, Zhang Z, Lehrer D et al. “Detection of Breast Cancer with Addition of Annual Screening Ultrasound or a Single Screening MRI to Mammography in Women with Elevated Breast Cancer Risk.” JAMA. 2012;307(13):1394-404.

27. Tabar L, Chen THH, Yen AMF et al. “Detection, Diagnosis and Treatment of Early Breast Cancer Requires Creative Intedisciplinary Teamwork.” Semin Breast Dis 2005.8:4-9.

July 30, 2024

July 30, 2024