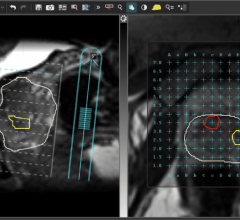

Fractional flow reserve-computed tomography (FFR-CT) is still in the early stages of clinical implementation in the United States, but it is already changing clinical practice as a non-invasive alternative to diagnosing patients with chest pain. Approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in November 2014, the technology provides both anatomical and functional assessment of the coronary arteries, a task no other method has accomplished to date.

DAIC spoke with three users of the HeartFlow FFR-CT technology, each in various stages of clinical practice:

● James Min, M.D., professor of radiology and medicine and director of the Dalio Institute of Cardiovascular Medicine, Weill Cornell, New York-Presbyterian Hospital, has been using the technology since April 2015;

● Geoffrey Rose, M.D., FACC, FASE, cardiologist at the Sanger Heart & Vascular Institute-Charlotte (N.C.), Carolinas Healthcare System, began using FFR-CT in late 2015; and

● Bjarne Norgaard, M.D., Ph.D., Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark, has the most experience with FFR-CT, having used it in clinical practice for two years and in a research capacity for three years prior.

Each practitioner’s experience has been unique, but all three are seeing the benefits of this groundbreaking technology.

Watch a video interview with HeartFlow's CMO about the FFR-CT technology at ACC.16

Current Practices

At present, there are a variety of methods available to identify suspected coronary artery disease, each offering advantages and disadvantages in terms of sensitivity and specificity. Regardless of the method used, the majority of patients end up in the cardiac cath lab for invasive angiogram and potentially a catheter-based FFR measurment.

Recent data suggest, however, that many of these patients are being sent to the cath lab unnecessarily. A three-year retrospective study published in the June 2014 American Heart Journal found that nearly 60 percent of 661,063 patients referred for elective angiography had non-obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) — nearly two-thirds of these patients sent to the cath lab did not have a clinically significant coronary disease.[1] “We’re sending two out of three patients to get an invasive, expensive procedure for no reason,” Min told DAIC.

CT angiography has provided a non-invasive option for assessing the coronary arteries by visually confirming the presence of stenosis. This is still not a perfect test, according to Rose. “The Achilles heel of CT angiography has been when we have intermediate lesions, we don’t know what to do with them,” said Rose. “The sensitivity is terrific, but the specificity is not very good.”

Clinical Trial Benchmarks

Performance benchmarks for FFR-CT have been established through a few major clinical trials, most prominently the PLATFORM trial out of Europe. Ninety-day results, presented at the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics (TCT) meetings last year, revealed the need for invasive coronary angiography was eliminated in 61 percent of patients. FFR-CT also had a significant impact on economic and quality-of-life (QOL) outcomes. Mean costs were 32 percent lower for FFR-CT patients in the noninvasive testing stratum, compared to those who underwent coronary angiography. A sensitivity analysis found costs were still lower for the FFR-CT group even when the cost weight of the technology was set to seven times that of CT angiography.

The rate of reduction for cath lab admissions remained the same in the one-year results, presented at the 2016 American College of Cardiology (ACC) annual scientific sessions in April. Furthermore, none of that group had experienced an adverse clinical event after one year. On the economic side, FFR-CT evaluation resulted in a 33 percent cost savings to the healthcare system compared to patients who received standard care.

The impact of FFR-CT on treatment decisions was further corroborated in the FFR-CT RIPCORD Study, presented at the EuroPCR 2015 conference last May. Three experienced cardiologists reviewed coronary CT angiography images of 200 patients with stable chest pain and agreed on one of three treatment options: optimal medical therapy, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or coronary bypass surgery. The physicians were then shown the FFR-CT analysis for each patient and asked to make a second treatment decision. In total, reviewing the HeartFlow data resulted in a change in treatment plan for 36 percent of patients. Also of note, in 18 percent of the cases initially decided for PCI, one or more of the target lesions was changed following FFR-CT analysis.

Patient Selection

One of the biggest clinical questions about FFR-CT is which patients are best suited for evaluation. The technology seems to have found a niche in assessing CAD in patients with intermediate lesions, particularly those where multiple lesions are present. In these cases, the technology can help determine if any of the lesions are severely limiting blood flow and/or which lesion(s) are the most significant. “If you’re doing a CT angiogram and there’s clearly high-level, multi-vessel disease, there’s very little incremental information we’re going to gain by using FFR-CT,” Rose said. The same is true for the other end of the scale, as smaller lesions are unlikely to have a significant impact on blood flow. All three users define “intermediate” lesions as those with blood flow capacity limited to 40 to 70 percent.

At Sanger Heart & Vascular Institute, all patients whose CT angiograms reveal intermediate lesions are qualified for FFR-CT analysis. The difficulty, Rose told DAIC — and one that is faced by hospitals across the United States — is that CT is rarely a first-line diagnostic test for chest pain patients since the sensitivity and specificity are lower compared to nuclear myocardial perfusion imaging (MPI) and other modalities. This second-line status also means that CT angiograms are often not covered by insurance providers.

The situation is different for Norgaard in Denmark, where CT is a first-line diagnostic test conducted for all patients presenting with chest pain. Like with other users, Aarhus University Hospital requests FFR-CT analysis for patients with one or more stenoses of 40-70 percent. Norgaard estimated this comes out to 15-20 percent of patients.

At Weill Cornell/New York-Presbyterian, Min said the primary venue for FFR-CT is in the emergency department and all CT scans are sent to HeartFlow for FFR assessment.

Benefits of FFR-CT

Early clinical reports indicate FFR-CT has indeed helped reduce the number of patients referred for unnecessary catheterization procedures. Many of the institutions using the technology are still gathering hard data, but Rose and Norgaard have both noticed changes in their respective practices. Rose estimated that 30 percent of patients submitted for FFR-CT analysis have been sent on to the cath lab, a significant reduction for Sanger Heart & Vascular Institute.

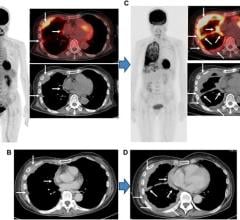

While hard data may be lacking, anecdotal evidence reinforces the benefits of FFR-CT. Rose recalled performing a HeartFlow analysis on a very obese woman who had come into the office with chest pain. Nuclear stress test results were normal, however the patient continued to show symptoms. Sending her to the cath lab carried additional risk due to her obesity, so the team performed a CT scan — at less than 3 mSv of radiation dose — and identified significant obstructive coronary disease, which was confirmed through invasive FFR. “The correlation was perfect, she was stented and she’s doing great,” Rose said.

Norgaard spoke of a recent patient who was experiencing chest pain over the course of several months. The patient, whose brother had died at a very early age of cardiovascular disease, had several angiograms performed and underwent two catheterizations, all of which came back normal. Eventually, a CT scan revealed no stenoses but did reveal severe CAD. Further FFR-CT analysis found very low values in the left anterior descending artery, which was confirmed through invasive FFR. The patient ended up having coronary bypass surgery and made a full recovery. Cases like this illustrate what Norgaard says is FFR-CT’s primary role: that of gatekeeper to the cath lab.

Beyond just keeping patients out of the cath lab, though, the technology can be used as a decision-making tool before performing revascularization. Aarhus University Hospital has seen a major shift in its approach to diagnostic testing: Norgaard noted that prior to implementing FFR-CT, the hospital did 300-350 myocardial perfusion scans per year; in 2015, it performed 300 FFR-CT scans only 30 MPI scans. “We have totally replaced myocardial perfusion imaging,” he told DAIC.

Rose spoke of a young man (<30 years old) with a family history of significant coronary disease who presented with chest pain. A CT angiogram revealed high-grade plaque in the left anterior descending artery approaching 50 percent but the FFR-CT scan was normal. As a result, the healthcare team was able to work with the patient on preventive measures and lifestyle changes.

“I think it has streamlined it more than anything,” Min said of the impact on cardiac care. “In addition to streamlining care and preventing people from having to undergo two tests, it gives a higher sense of diagnostic certainty, which is difficult to quantify but is good for the diagnostician and the patient.”

Limitations of FFR-CT

While the technology has shown considerable promise, it is by no means the perfect diagnostic test. Under the current model of FFR-CT analysis, where data has to be sent to HeartFlow for FFR calculation and sent back to the hospital, turnaround times are a concern, particularly for emergency department cases. Rogers told DAIC that HeartFlow hears this concern frequently from providers and that the company has been asked about licensing out the technology so calculations can be done in-house.

“Our technicians and operators use our tools in an incredibly controlled environment, much like the manufacturing of a medical device, and that’s where the precision reproducibility comes from” Rose said. He added that giving the software to hospitals would put the onus on the physician, who likely has not had the same training as a HeartFlow operator, to perform the calculations, which could impact the accuracy, speed and reproducibility.

The other limitation of the technology is that the FFR calculations can only be as precise as the CT images allow, and Norgaard noted that false-positives are still a risk, “but we have had conclusive results in more than 95 percent of cases,” he said.

Norgaard said it took about a year of clinical use to convince his cardiology department that the technology was worth the investment

Read the related 2018 article "New Cardiovascular CT Technology Entering the Market."

References:

1. Patel, M.R, et al. “Prevalence and predictors of nonobstructive coronary artery disease identified with coronary angiography in contemporary clinical practice,” American Heart Journal, June 2014.

2. Cerqueira, Manuel D., et. al. ASNC Information Statement, “Recommendations for reducing radiation exposure in myocardial perfusion imaging,” May 26, 2010.

August 09, 2024

August 09, 2024