February 22, 2017 — When Children’s Hospital Los Angeles cardiologists found evidence that a portion of Nate Yamane’s pulmonary artery they had repaired once before was again narrowing, pediatric interventional cardiologist Frank Ing, M.D., decided they needed to insert a stent to keep the right artery open.

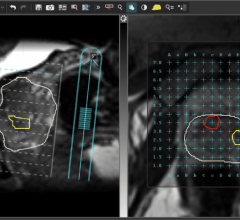

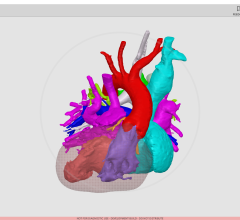

But due to the size of the narrowing, about 9 millimeters, doctors needed to customize the stent to fit into the smaller space and they wanted to perfect their measurements before the actual procedure. Using computed tomography (CT) scans of Nate’s heart, they created a 3-D printed model of the obstructed region. Ing was then able to fashion a smaller stent to fit precisely into the narrowed artery in the model.

"I have to say, the 3-D model was very helpful because it gave me confidence that [the size of the stent] was going to work," said Ing.

Born in June 2015 with tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) with pulmonary atresia, the 7.1-pound infant Yamane had trouble breathing shortly after birth. The cause: a genetic abnormality resulting in heart defects that obstructed his pulmonary artery, preventing blood pumped by the heart from flowing into the lungs.

He was rushed to Children’s Hospital Los Angeles from a South Bay hospital in critical condition. Pulmonary atresia — a more severe version of TOF — occurs when the pulmonary artery fails to form properly in utero, prompting the human body to grow collateral arteries that redirect blood around the obstruction and to the lungs (a typical development with these types of blockages). About one in 10,000 children are born with this congenital heart defect.

“Imagine blood flowing in the artery like cars on the freeway, and it’s blocked. Cars exit and find an alternate route to its destination; blood does the same, and in this case finds its way through collateral vessels to the lungs,” explained Ing, the chief of the Division of Cardiology and co-director of the Heart Institute at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles.

But after birth, those vessels need to be rebuilt quickly or the heart will fail. Using a surgical technique called unifocalization, surgeons can repair the vessels by sewing them together. “We use whatever the body gives us,” explained Ing, a professor of clinical pediatrics and medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California.

A month into his young life, Nate had undergone two open-heart surgeries and a catheterization procedure, but doctors were not done. In December 2015, Nate's pulmonary arteries were found to be narrowed in both the right and the left branch. At the time, a team led by Ing was able to use a balloon to open the right side. However, to keep the left section open they had to insert a stent, specially modified using a technique developed at CHLA, to fit the narrowed portion of the child's left pulmonary artery (about 15mm). Stents do not normally come that small, but by carefully cutting their smallest existing stent and folding it back upon itself, Ing tailored a functional custom stent that worked perfectly and did not jut out needlessly into other areas.

Almost immediately, Nate saw marked improvement in blood flow, including a healthy drop in blood pressure. Still, in the coming months, he gained little weight and had to grow bigger and stronger before considering another procedure. “We did physical therapy and tried to fatten him up,” said Nate’s mother, Courtney.

Watch the VIDEO "Use of 3-D Printing To Help Guide Structural Heart Intervention."

On Jan. 19, 2017, Ing inserted the second, even smaller stent into Nate’s right pulmonary artery in CHLA's catheterization lab before an international audience of cardiologists watching on a live video feed at the Pediatric and Adult Interventional Cardiac Symposium in Miami. Using the stent that was modified in advance to the same specifications in the model, Ing and his team were able to open up Nate's right pulmonary artery, with successful results; Nate’s oxygen levels improved overnight.

In the months and years ahead, Nate will need additional surgeries, but his weight is up to 21.5 lbs., and he’s eating better and getting stronger. “He’s rolling around with energy and even took his first baby steps,” said Courtney, who also has a four-year-old at home. “There’s a big difference and a lot of improvement. We’re going in the right direction.”

Read the ITN feature story "The Future of 3-D Printing in Medicine."

For more information: www.chla.org

August 09, 2024

August 09, 2024