Diagram 1

Medical device companies spend around $1 million at the front end of every device development project to get to a product concept that they want to take to market. Some vendors spend it better than others, according to Sagentia, a company that works with device vendors to develop new technologies, products and services.

The company recently conducted research among 20 big-name medical device companies to identify areas of best practice in front-end innovation. The intent was to share that insight and help companies get the most out of their investments.

Among the study's findings, the single largest determinant of what practices one ought to adopt is competitive stance. This means a company aspiring to lead in its sector will need to be more sophisticated in its execution of the front end than a company whose competitive strategy is one of fast-follower. If a business unit expects to be the disruptor in its market niche, it will likely need to consider many of the practices and tools described here for implementation. The tools can be broken into groups – those that will take a vendor to new needs and procedures (markets) and those that will take them to new solutions (technologies).

The definition of front end Sagentia used was a set of activities that deliver a bullet-proof investment case around a product concept that will release the multi-million dollar budgets required for downstream product development. These factors include system design, detail design, prototyping, clinical trials and transfer to manufacturing.

Although everybody agrees that innovation is a major contributor to competitive edge, it does not follow that everybody does it well. Some organizations seem to be true innovation sophisticates, while others struggle to make sense of how to nurture opportunities into strong product concepts that warrant further investment. Sophistication is required of both market and technology research methods. Importantly, being good at one is no indicator of being good at the other.

So, how can a medical device company achieve the best value from its first million bucks? In this article we discuss a series of best practices to answer that question.

Understanding the Innovation Mandate

Executives who operate at the front end need to recognize what type of innovation mandate they have so that they can put in place an appropriate structure to support it. Although all companies have an underlying innovation mandate that is part of their corporate strategy, not all can articulate their mandate well. So while all front-end executives are usually able to directly relate their role to an overall financial growth agenda, only some are able to point to a link between their company’s competitive position and their particular innovation program. An example of such a link would be “we aim to be No. 1 in Chinese laparoscopic surgery, and hence we are undertaking this kind of research.”

Businesses with a competitive strategy that requires them to be number one or two in a given medical market must deliver product and service differentiation to that market. In this situation, the group or individual operating at the front end needs to be a “front-end sophisticate” and should both understand their challenge and feel confident and justified in seeking funds for projects that don’t have a guaranteed outcome. The best front-end innovators in these types of businesses will have that zeitgeist; they live it, breathe it and feel entirely comfortable with it.

Recognizing Radical

A sophisticated approach is an absolute prerequisite for any front-end innovation that hopes to deliver a new market benefit or new technology. The data upon which these breakthrough products are based, and upon which decisions are made, are usually very thin. This is the nature of disruption – if the precedent existed it wouldn’t be radical.

In these situations, if usual screening rules were to be applied, budget requests to support these kinds of endeavors would be rejected out of hand. Consequently, governance of high-risk activities calls for an alternative approach and it needs to be recognized from the outset that the project being evaluated requires different handling. We believe there are three elements to ensure this happens: the people, the tools and the processes.

People: Marketing vs. R&D

Most executives come with either an R&D sensibility or are rooted in marketing. Few R&D innovators cross the floor into marketing. Even fewer marketers move into R&D. This lack of common ground was a problem 10–15 years ago and remains so today.

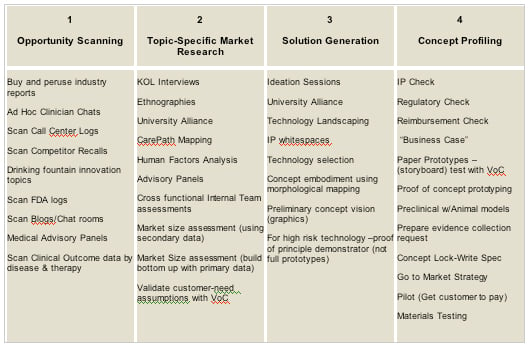

The shortfalls apparent in both marketing-led and R&D-led innovation are all too obvious. Marketing-led innovation falls short in the solution generation steps, in some cases relying too much on two-day creativity workshops to respond to months of careful market research. There are better tools available, outlined in diagram 1. The corollary is also true; R&D-heavy teams leading innovation efforts are often blind to the range of market research tools available at either the opportunity-scanning or topic-specific market research steps. Awareness and acceptance of these gaps is critical, and efforts to share tools and bridge them will significantly improve outcomes.

Process 1: A Four-Step Program

Are organizations systematic or serendipitous about how they initiate a program? From anecdotal evidence, we have found the use of systematic analysis is very much on the increase in the medical devices industry. While the stereotypical image of a CEO popping his head around the door to R&D, scratching his chin and proclaiming, “we need to be bigger in imaging” remains (and in a small number of cases is still the case), it is encouraging that this haphazard approach is diminishing rapidly. The CEO instruction was, in reality, filling a void. Now that the analytical tools exist, they are being used at the expense of top-down instruction.

Developing this point further, Sagentia offers the following approach as a simple but clearly defined four-step program.

1. Opportunity scanning – The sampling of information across a broad range of topics (clinical procedure, clinician group, market trend or even technology opportunity) with the goal of identifying a theme to exploit. This is the stage which, until recently, was fulfilled by the “visionary CEO.”

2. Topic-specific market research – Having settled on a topic, data is sought to qualify the opportunity hypothesis. This data takes two forms – quantitative data on the size and growth of the topic, and qualitative data on the target user’s subtle needs relating to it.

3. Solution generation – Solution generation and filtering in which we explore both technology and design.

4. Concept profiling – The final stage in which the concept is “bullet-proofed” prior to governance scrutiny, ensuring that all stage exit criteria are addressed.

Process 2 - A Bullpen of Opportunities

Sagentia’s research indicates a shift in the medical device industry (and other sectors, such as consumer products) toward a “bullpen” where projects are gathered together and viewed as a whole. The bullpen portfolio approach – as opposed to a traditional process which considers individual projects in isolation and on their own merit - has been shown to provide, on aggregate, an improvement in success rate. Here’s why:

• “Best work” is encouraged and undertaken through competition (not between teams per se, but between market opportunities)

• A discipline is established that kills floundering projects and swiftly re-assigns budget into awaiting projects

• It will help ensure that R&D budgets are fully spent. A common misconception among middle managers is that under-spending R&D budget is a good thing. Sagentia’s experts disagree with this position, arguing that an under-investment in R&D is an under-investment in growth.

Tools

Organizations seem to focus on the areas of front-end innovation where they have internal resources and proven strengths. For example, depending on who is running the show – i.e., marketing or R&D – the focus will be weighted accordingly. This approach is limiting and requires sponsors to make decisions with incomplete evidence. We believe companies should consider their areas of weakness and explore the full range of tools available to address them.

The following tools are an aggregation of those being used amongst front-end innovation executives in large, sophisticated medical device organizations:

What is encouraging to note here is the sheer diversity of tools that are now available, coupled with the fact that many of these tools are new to the medical device industry. On the market research side for example, “care path mapping” is a tool to determine triggers for replacing entire medical procedures in light of the move towards preventative rather than curative interventions. On the R&D side, technology landscaping is a means to explore technology solutions from adjacent industries for application in a medical setting.

In some instances, these tools are being deployed and managed directly by the medical device company. For some of the more specialist tools, or where adequate in-house expertise and resources do not exist, outside consulting services are being retained. Indeed, the ratio of internal spend (salary and benefits) to external spend (consultancy) averages 1:3 in favor of external spend. In other words, of that $1 million described earlier, $750,000 is being incurred as a direct expense.

Beyond Voice of the Customer (VoC) Research

All companies point to needs as the single most important innovation driver. So much so that VoC has, over the past 20 years, become the established industry mantra. Any talk that questioned its validity was seen as verging on the heretical. Change, however, is on the horizon. While there is still appropriate reverence for the opinions and insights voiced by clinicians, there are shortcomings to only listening to customers:

• Clinicians are sometimes poor at self-reporting. Recognizing that most thought is unconscious, what level of false-reporting or noise do we introduce when we interview (rather than observe) a clinician?

• Practitioners are often blind to disruption. Clinicians’ intellectual investment in the current standard of care (a given procedure) will often render them blind to, or simply unaware of, the potential for disruption at procedure level.

• Key opinion leaders as a particular segment of the clinical population commonly sought out are sometimes the wrong voices to listen to. Less skilled clinicians/users are an overlooked constituency and a larger market segment.

The over-arching point here is that the tool and its applicability needs to be fully understood. Before initiating any research, a prudent innovator should have a hypothesis as to where insight will come from and chose a research method (or methods) accordingly.

Take a laparoscopic gall stone removal, for example. If ethnographic research is undertaken in isolation, then insights will be gained into the limitations of current technologies. This will lead to ideas for new gall stone removal technologies. But there may well be an entire procedure-disruption angle. There may be a yet-to-be-discovered drug that will obviate the need for surgery entirely by preventing a stone from forming in the first place. And if you have a surgical tools franchise that serves this market, you may miss a billion-dollar disruption to your annual revenue.

Conclusion

With typical medical device budgets for front-end work around the $1 million mark, it is clear that the industry recognizes the crucial position this early activity occupies within the innovation function. The key, however, is to make this investment valuable.

If a business unit expects to be the disruptor in its market niche, it will likely need to consider many of the practices and tools described here for implementation. The tools can be broken into groups – those that will take you to new needs and procedures (markets) and those that will take you to new solutions (technologies).

If an innovation function is being led by a marketing executive, it would behoove that executive to consider sophisticated solution research and creation tools. It is not enough to simply "hand-off" a marketing brief to the company’s line extension technology team – they will likely reduce the opportunity with "business as usual" solutions. There is more to solution building than brainstorming workshops. And similarly, R&D-led functions should challenge their level of market interrogation savvy to see how wise they really are to the unmet needs of their customers. There is more to market research than clinician interviews.

To the front-end sponsors perhaps reading this, we would counsel you to let your front-end innovation function mature into the delivery engine it needs to be to address your competitive agenda. Perhaps there are some governance and operational practices that can be adopted from those discussed here. A strong message from the research is that we should not allow organizational structure legacy and tradition impede performance.

To the front-end “doer” we would recommend you look at the toolbox you are drawing from and the bias that your background brings to your challenge. There are several tools listed in this report that might warrant a trial run.

Editor’s Note: Dan Edwards is vice president at Sagentia, based in Harston Mill, Harston, Cambridge, in the United Kingdom. The company has been focused on product development in the medical and healthcare sector for 20 years. Its clients include some of the world’s leading medical technology and life science businesses. If interested in receiving the complete Sagentia research report, contact Dan Edwards by e-mail at [email protected]. For more information, visit www.sagentia.com.

December 01, 2025

December 01, 2025