May 7, 2014 — The American College of Radiology (ACR) and Society of Breast Imaging (SBI) agree with statements by Andorno and Jüni, in their recent article published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), that women need clear information with which to discuss mammography with their doctor. Unfortunately, the NEJM article failed to meet this standard. The deadly consequences of the authors’ breast cancer screening recommendations to the Swiss government may take years to become evident, may yet affect women in the United States and were minimized — if included in the article at all. According to the ACR, the lack of a counterbalancing perspective, in such a major scientific journal, is surprising and concerning. American women should pay close attention to the breast cancer screening policies that may be considered for them, ACR and SBI said.

According to the ACR and SBI, If routine breast cancer screening of all women were ended in the United States, 15,000-20,000 additional women each year would die from breast cancer. Thousands more would endure extensive and expensive treatments than if their cancers were found early by a mammogram. Restriction of current screening would also cost lives. In 2009, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) suggested that women ages 40-49 not receive routine annual screening and those 50-74 receive biennial screening. Analysis (Hendrick and Helvie), published in the American Journal of Roentgenology, using the Task Force’s own methodology, showed that if these USPSTF guidelines were followed, approximately 6,500 additional women each year in the U.S. would die from breast cancer.

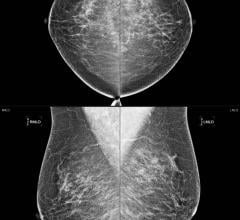

The NEJM authors’ claim that mammography does not save many lives through early detection of tumors is false, ACR and SBI said. According to National Cancer Institute data, since mammography screening became widespread in the mid-1980s, the U.S. breast cancer death rate, unchanged for the previous 50 years, has dropped well over 30 percent. Recent randomized control trials, particularly the largest (Hellquist et al) and longest running (Tabar et al) breast cancer screening studies in history respectively, have reconfirmed that regular mammography screening cut breast cancer deaths by roughly a third (not the 20 percent cited by Andorno and Jüni) in all women ages 40 and over — including women ages 40–49. A study (Otto et al) published in Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention shows mammography screening cuts the risk of dying from breast cancer nearly in half. A recent study published in Cancer showed that more than 70 percent of the women who died from breast cancer in their 40s at major Harvard teaching hospitals were among the 20 percent of women who were not being screened. When discussing doing away with screening programs that have been proven to save thousands of lives each year, this information is critical, ACR and SBI noted.

The NEJM authors point to the Canadian National Breast Screening Study (CNBSS) to support claims of over diganosis and lack of mammography effectiveness. Balanced information that the CNBSS has been widely discredited is not included. The World Health Organization long ago excluded the CNBSS from its analyses of screening mammography’s impact of breast cancer mortality. In a recent interview with CNN, the American Cancer Society echoed methodological concerns about the study. Breast cancer groups, such as BreastCancer.org, have also criticized this study and warned against following the author’s recommendations.

Medical science, at present, cannot determine which cancers will advance to kill a woman and which will not. As recently covered in the New York Times, estimates of over diagnosis or overtreatment are not based on data regarding real patients, but are guesses based on population data that may be wildly off-mark. A recent article published in The Oncologist shows that many studies regarding over diagnosis and potential harms of mammography are not well founded and that their conclusions cannot be taken as fact. Yet, the NEJM authors advocate that widespread screening programs be ended, resulting in thousands of unnecessary deaths each year, based on such guesses. The ACR and SBI cannot support such a step.

Every major American medical organization with expertise in breast cancer care, including the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ,American Cancer Society, American College of Radiology, National Accreditation Program for Breast Centers and Society of Breast Imaging recommend that women start getting annual mammograms at age 40. The ACR and SBI said they continue to stand by these recommendations.

Mammography can detect cancer early when it is most treatable and can be treated less invasively — which not only save lives, but helps preserve quality of life.

For more information: www.MammographySavesLives.org

July 29, 2024

July 29, 2024