May 13, 2022 — Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, one of the major causes of dependency and disability in older adults. Though advances have been made in understanding the harrowing brain disease, diagnostic tests are currently limited and there are no treatments.

Now, an Ottawa Faculty of Medicine assistant professor and a team of collaborators have published new research suggesting that a novel neuroimaging technique can potentially be employed in large-scale screenings for Alzheimer’s. It can also provide possible insights about the disease’s earliest stages, long before symptoms emerge.

The findings could help steer targeted drug design down the line and perhaps pave the way for a practical, less-invasive way to screen for Alzheimer’s, which can lead to such severe cognitive decline that sufferers can lose the ability to recognize loved ones or even communicate at the most basic level.

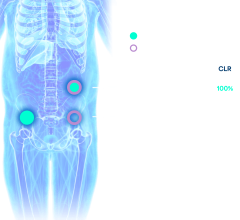

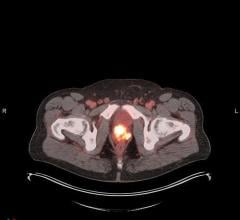

Published recently in the peer-reviewed journal Neuropsychopharmacology, the scientists’ study suggests that use of a high-resolution imaging method called “neuromelanin-sensitive MRI” could have promise for predicting the risk of symptoms or guiding future treatment.

Dr. Clifford Cassidy, an assistant professor in the Faculty’s Department of Cellular & Molecular Medicine (CMM) and a scientist at The Royal's Institute of Mental Health Research (IMHR), is the paper’s first author. The research was conducted in collaboration with the McGill Centre for Studies in Aging as part of a large study including healthy older adults, those at risk, and those with dementia.

Their findings confirm previous data that the brain’s noradrenergic system is progressively degenerating with Alzheimer's disease. This brain system is vitally important because it may be the first area affected with Alzheimer's and its pathology is related to the disorder’s symptoms.

For instance, the researchers found strong evidence that the integrity of the noradrenergic system is related to behavioral symptoms of one of Alzheimer's most burdensome aspects: aggressive and impulsive behavior.

“These behaviors are often what lead people to going into homes and not being able to live independently anymore,” Cassidy said.

He says the study demonstrates a practical method to track pathophysiology in people with Alzheimer’s or those at risk. Previously, this was only possible using methods that could only be used on a small scale or in post-mortem studies.

“We still don't understand why some people get Alzheimer's and some don't. We don't know why some people are protected and some are vulnerable. So the question is: What makes you vulnerable?” he says.

Tens of millions of people across the globe are estimated to have Alzheimer’s and the prevalence of the brain disorder is only accelerating with the aging of the global population. A protein called “tau,” which forms tangles in Alzheimer’s patients’ neurons, is the disease’s key marker.

The specialized MRI technique visualizes neuromelanin, a dark pigment related to the melanin that colors skin, in the control center of noradrenaline neurons. This is important because “there's evidence that the noradrenergic area of the brain is the part that actually starts accumulating tau first, years prior to the emergence of any symptoms” Cassidy said.

Alzheimer’s was examined in this study, but Cassidy is pioneering the use of this imaging method in different contexts, exploring how it might answer different questions for a wide range of psychiatric conditions. There’s a wealth of possibilities, Cassidy said.

The neuromelanin-sensitive MRI has been used to visualize degeneration of neurons in Parkinson’s disease and healthy aging. Schizophrenia and addiction have been examined. Cassidy and colleagues are next exploring its relevance for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

“It really opens the door to examining these brain systems in humans, in vivo, in pretty much any disorder where it can be relevant. After all, if it is telling you something about the dopamine system or the noradrenaline system, those are two brain systems that are relevant for almost any condition in neurology or psychiatry,” he said.

Cassidy began collaborating with these McGill colleagues starting in 2018 and convinced them to add the neuroimaging technique to complement the many other measures available. This is the first publication from this collaboration, but their work is ongoing. Future papers will look at the data in different ways and better incorporate longitudinal datasets to observe changes over time.

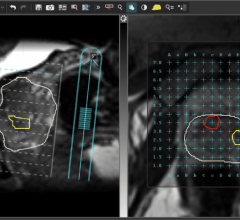

Cassidy has developed a fully automated method of how to look at the “neuromelanin-sensitive MRI” images. Previously, this work required manual tracing, making it very labor intensive and subjective. Now, a computer system handles the raw images.

There are hopes for commercialization. Cassidy and colleagues have partnered with a biotech company and a software company to develop their tools into a software package. It is awaiting approval from the FDA.

“This will ensure our tool could have the potential for clinical use by being fully automated and reliably provide neuroimaging measures without any manual step required or expert intervention. This is an advantage over many tools used in neuroimaging research that require much time and effort by experts in order to yield useable metrics from the raw images collected off the scanner,” he said.

For more information: https://www2.uottawa.ca/en

Related Alzheimers' content:

FDA Grants Accelerated Approval for Alzheimer’s Drug Aduhelm

VIDEO: Researchers Use MRI to Predict Alzheimer's Disease

Brain Iron Accumulation Linked to Cognitive Decline in Alzheimer's Patients

Good Results for Alzheimer’s Imaging Agent

NIH Augments Large Scale Study of Alzheimer’s Disease Biomarkers

Alzheimer’s Association Launches New Website for IDEAS Study

PET Tracer Gauges Effectiveness of Promising Alzheimer's Treatment

July 30, 2024

July 30, 2024