November 4, 2019 – Two new studies support and inform the use of proton radiation therapy to treat patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), a common but often fatal type of liver cancer for which there are limited treatment options. One study (Sanford et al.) suggests that proton radiation, compared to traditional photon radiation, can extend overall survival with reduced toxicity. A second study (Hsieh et al.) identifies predictors for reducing liver damage that can result from radiation treatments. Both studies were published in the International Journal of Radiation Oncology • Biology • Physics, the flagship scientific journal of the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO).

"There is hope for patients with liver cancer, with more treatments becoming available in recent years," said Laura Dawson, M.D., president-elect of ASTRO and a professor of radiation oncology at the Princess Margaret Cancer Center in Toronto. "These studies show that protons, like photons, may be used to treat patients with HCC with a high rate of tumor control and a reduced risk of adverse effects."

HCC is the most common type of liver cancer and a major contributor to cancer deaths worldwide, with more than 700,000 deaths globally attributed to the disease each year. Its incidence is rising, both nationally and around the world.

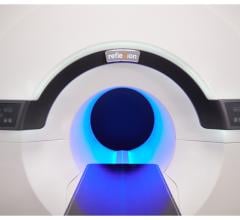

Treatment options include liver transplants, surgical resection, ablative procedures and radiation therapy – either photon (traditional radiation therapy, which uses x-rays or gamma rays) or proton radiation therapy (which delivers more targeted radiation using positively charged particles at very high speeds). While surgery remains the preferred treatment, donor livers are scarce and many patients are not eligible for surgery due to underlying conditions, such as cirrhosis.

Proton radiation improves overall survival

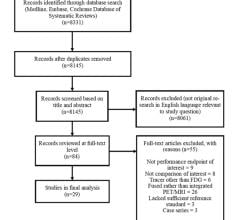

The first study, from Nina Sanford, M.D., and colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital, compared outcomes for patients treated with the traditional photon radiation therapy to those treated with proton therapy.

The study showed proton radiation was associated with better overall survival (median survival 31 months vs. 14 months, [HR, 0.47; P =.0008]) and decreased incidence of non-classic radiation induced liver disease (RILD) (OR, 0.26, P = .03), compared to photon radiation. Locoregional control was high for both treatment arms (93% for protons and 90% for photons) and did not differ between patient groups in this retrospective analysis of 133 patients treated at a single institution.

The authors concluded that the improved overall survival time for those treated with proton radiation therapy could be due to the lower occurrence of post-treatment liver decompensation.

"In the United States, patients with HCC tend to have underlying liver disease, which could both preclude them from surgery and make radiation therapy more challenging as well. So, having a therapy option that is less toxic could potentially help many patients," said Sanford, who is an assistant professor of radiation oncology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

"Proton radiation therapy delivers less radiation dose to normal tissues near the tumor, so for patients with HCC, this would mean less unwanted radiation dose impacting the part of the liver that isn't being targeted," she said. "We believe this may lead to lower incidence of liver injury. Because many patients with HCC have underlying liver disease to begin with, it is possible that the lower rates of liver injury in the proton group are what translated to improved survival for those patients."

The study is the first clinical comparison of protons and photons for patients with HCC, said Sanford.

Identifying predictors of liver damage

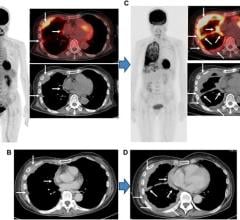

In the past, the role of radiation therapy for patients with HCC has been debatable, because the high doses needed to treat these tumors can result in liver disease (RILD).

A second study, from Cheng-En Hsieh, M.D., and colleagues, sought to identify metrics that predict RILD in patients treated with proton therapy. Researchers found that the volume of liver untouched by radiation was more important than the dose of radiation delivered for preventing treatment-related liver disease.

"Our data indicate that if a sufficient volume of the liver is spared, ablative radiation can be safely delivered with a minimal risk of RILD, regardless of dose," said Hsieh, a radiation oncologist with joint appointments at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and Chang Gung Memorial Hospital in Taiwan. "This is similar to hepatectomy (liver surgery), where sparing of sufficient liver volume allows a large portion of liver to be safely resected."

The researchers found RILD could also be predicted by tumor size, liver volume and severity of liver disease prior to treatment.

The importance of patient selection and personalized treatment

Knowing which metrics predict a greater risk for liver damage can help guide radiation oncologists in determining how to balance the benefits and risks of treatment, supporting a personalized treatment strategy, said Dawson.

"Both studies highlight a need for a personalized radiation therapy for the treatment of liver cancer," she said. "There is rationale for the use of protons for some patients, but the evidence to date is not sufficient for a general recommendation of protons as a preferred therapy above photon therapy for all HCC patients. Randomized trials, such as the ongoing NRG-GI003 trial, are needed to guide practice and better elucidate which patients may benefit from this treatment."

While proton therapy may offer advantages, it is both expensive and not easily available to most patients, noted Dawson and fellow authors in a comment letter published in the Red Journal in response to Sanford's study.

"At this juncture, protons remain a costly and limited resource, so further research optimizing patient selection for proton radiotherapy based on clinical factors or tumor biomarkers is needed," Sanford agreed.

"The task of balancing risk and benefit, at the core of radiation oncology, has never been more difficult," wrote the authors of an accompanying editorial. "Radiation oncologists are left with difficult decisions related to patient selection and optimization of radiation therapy, attempting to maximize local control and minimize toxicity in a patient population with underlying liver disease."

These studies "make valuable contributions to the field of liver radiation therapy" by providing information that can aid radiation oncologists with those decisions, the editorial concludes.

For more information: www.astro.org

August 09, 2024

August 09, 2024