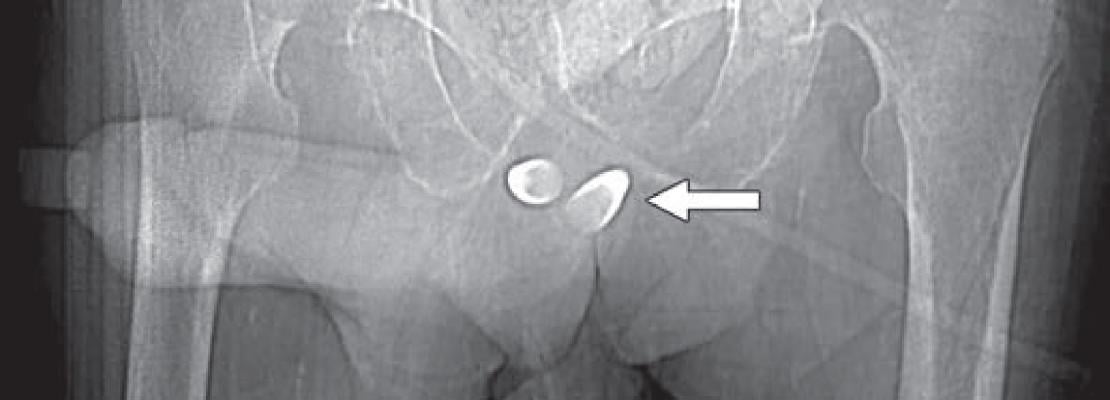

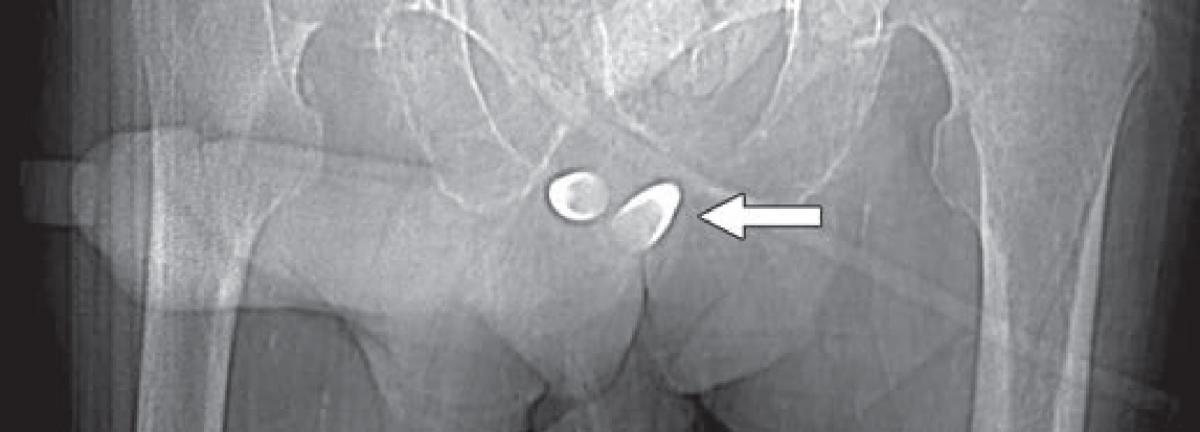

Scout image from contrast-enhanced CT shows erectile implant; stainless steel and silicone anchors (arrow) transfixed to pubic bone are asymmetric.

September 5, 2019 — An ahead-of-print article published in the December issue of the American Journal of Roentgenology (AJR) provides a primer of gender affirmation surgical therapies encountered in diagnostic imaging.[1] The article defines normal post-surgical anatomy and describes select complications using a multidisciplinary, multimodality approach.

Transsexual people, those whose gender identity is different from birth gender, often undergo hormone treatments and gender affirming surgeries to align their anatomy with their core identity. Medical imaging of gender affirmation surgery is not common in radiology, so this article set out to provide radiologists with some of the key radiologic identifiers.

With gender incongruence now categorized as a sexual health condition — no longer a mental illness — in the most recent revision to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), lead author Florence X. Doo, M.D., and colleagues at Mount Sinai West in New York City contend that all subspecialties must be prepared to identify radiologic correlates and distinguish key postoperative variations in the three major categories of gender affirmation surgery.

Genital Reconstruction

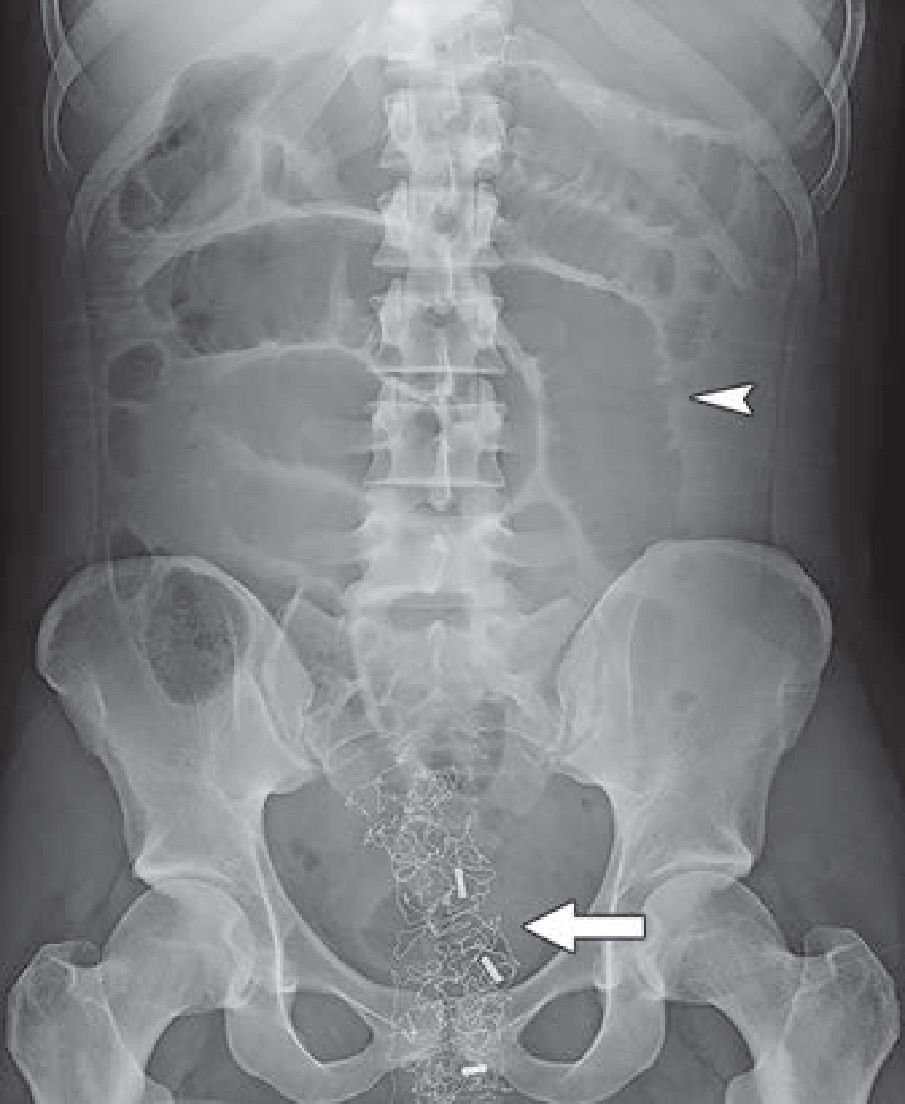

For trans-females, pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) remains the most reliable modality to evaluate the two most common complications arising from vaginoplasty: hematomas and fluid collection. Cellulitis, abscess, neovaginal prolapse and focal skin necrosis can occur, as well. As Doo cautioned, “At the end of the procedure, radiopaque vaginal packing is inserted, which should not be mistaken for other foreign bodies on postoperative imaging” (Fig. 1). Neovaginal fistulas present less frequently, and for most trans-female patients, these complications may be diagnosed on the basis of clinical symptoms and physical examinations. Although vaginoplasty typically preserves the prostate, it may have atrophied from adjuvant hormonal therapy with estrogen and progesterone, so regular prostate cancer screening guidelines should still be followed.

Fig. 1—Anteroposterior abdominal radiograph shows multiple dilated bowel loops (arrowhead) resulting from adynamic paralytic ileus and radiopaque foreign body (arrow) in pelvis.

When evaluating urethral complications from phalloplasty in trans-males, because the neo-to-native urethra anastomosis site will evidence diameter differences, retrograde urethrograms can result in stricture overdiagnosis. Apropos, preliminary assessments should be for functional stricture, alongside the performance of urodynamic studies. “However,” noted Doo, “for confirmation of stricture with abnormal function tests and also for evaluation for fistula, a retrograde urethrogram or voiding cystourethrogram can be obtained.” Should a patient desire erectile potential with the fully-healed neophallus, an implant may be placed, which is prone to infection, attrition, malposition and constituent separation (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 — Scout image from contrast-enhanced CT shows erectile implant; stainless steel and silicone anchors (arrow) transfixed to pubic bone are asymmetric.

For trans-males instead pursuing metoidioplasty (i.e., hormone-induced clitoral hypertrophy, followed by clitoral degloving and ligament detachment for neophallus lengthening), no penile implant presently exists that can sustain erectile rigidity for sexual function.

Body Contouring

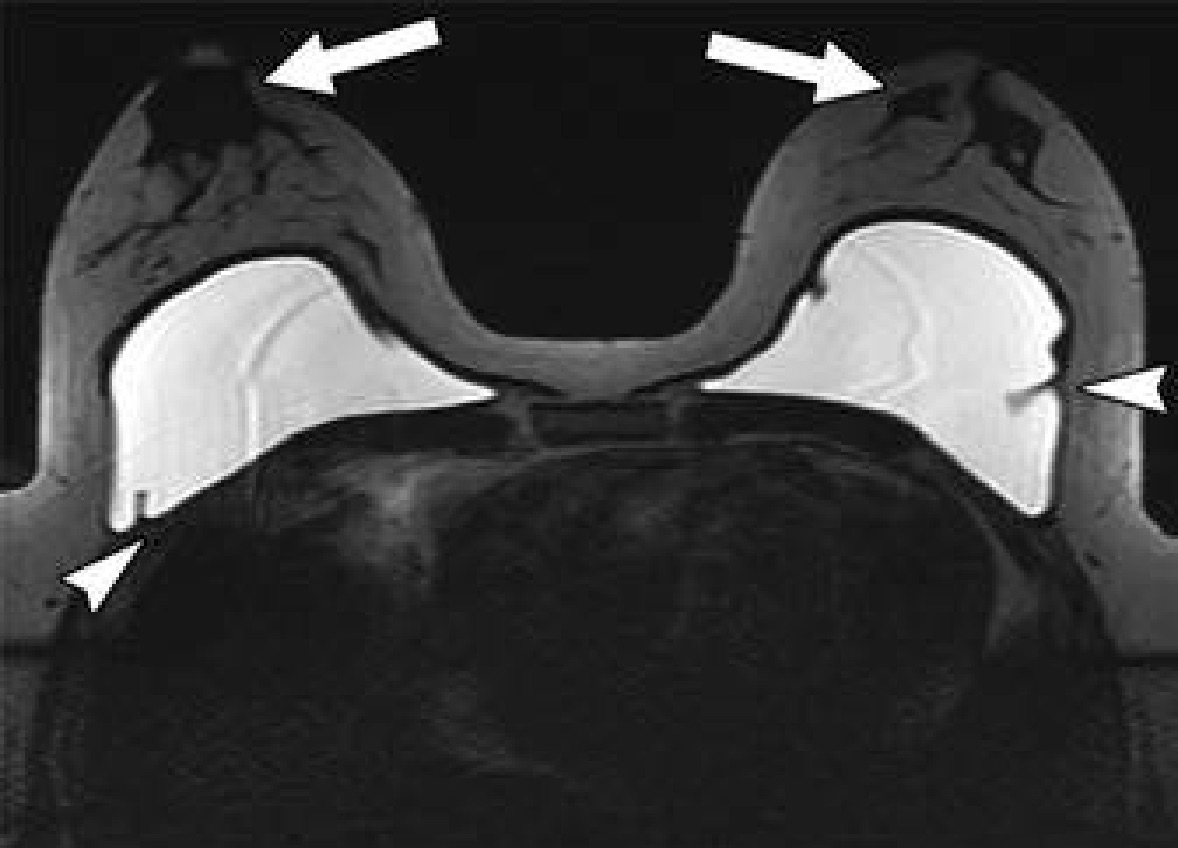

Related to gender affirmation surgery, silicone or saline breast implants in trans-females often evidence as incidental notations on chest radiography, computed tomography (CT) and MRI (Fig. 3), yet the most common body contouring gender affirmation surgery is subcutaneous mastectomy. Since the nipple-areola complex is preserved, retaining malignant transformation risk, Doo et al. recommend trans-males submit to regular postsurgical breast cancer screening. Likewise, trans-female patients who have undergone neoadjuvant hormone replacement therapy have an increased risk for breast cancer and should be routinely screened.

Fig. 3 — Single-shot fast spin-echo axial MR image of chest shows saline implants complicated by capsular contractions (arrowheads), with bilateral subareolar tissue (arrows) seen anterior to implants.

Regarding soft-tissue placement for desired aesthetic results, according to Doo: “The sequelae of fat augmentation, including complications such as fat necrosis, are seen incidentally on radiologic imaging and are not routinely evaluated postoperatively. Because of many factors, patients may instead choose to obtain gluteal silicone injections or implants, which may also be incidentally encountered on routine imaging, either as stand-alone findings or as complications including granulomas and emboli to the brain or lungs.”

Maxillofacial Contouring

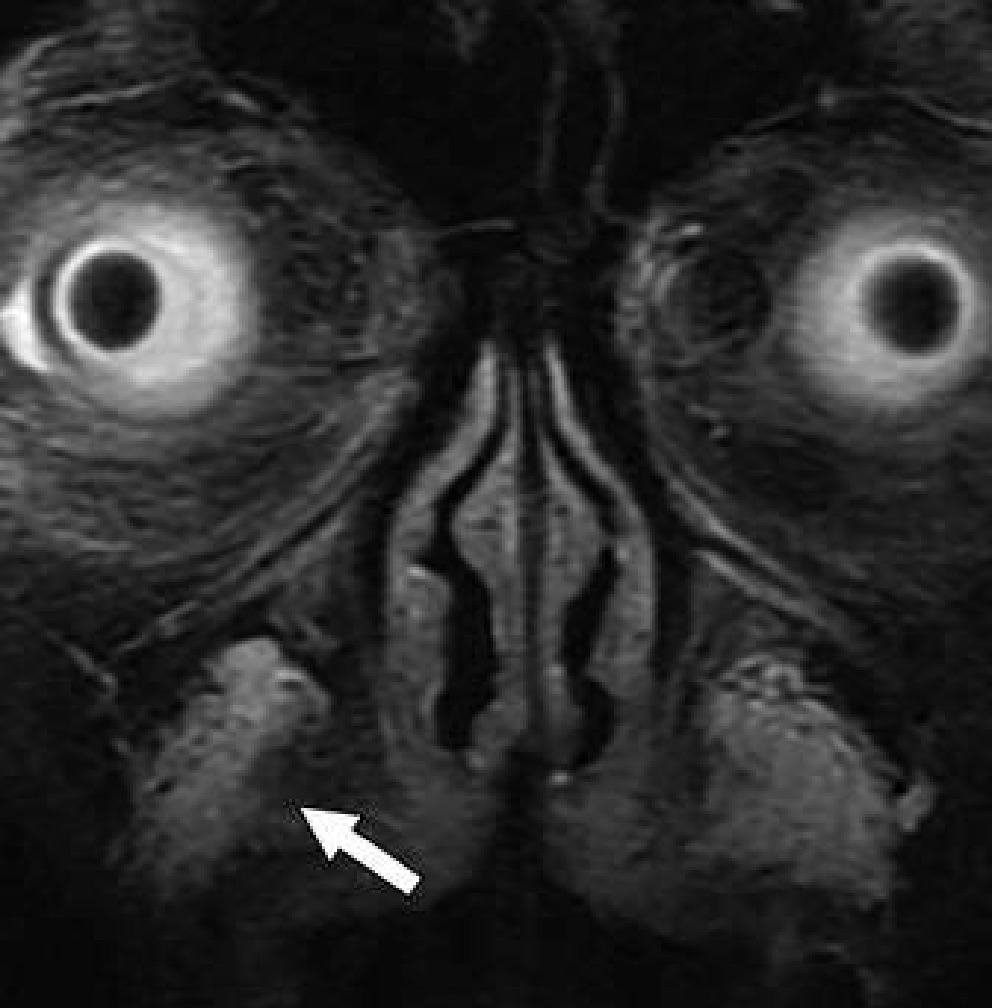

Pre-operative medical imaging, especially for facial feminization, is utilized to assess the anatomical need for frontal eminence reduction, with surgeons downstream referencing a skull radiograph to evaluate sinus cavity size and anterior table thickness. Meanwhile, Illegal silicone injections, long targeted toward all transgender populations, typically register incidentally on imaging studies, as do facial augmentations achieved via neurotoxin injections or fillers, such as calcium hydroxylapatite or hyaluronic acid. As Doo explained, “postoperative imaging is not typically obtained because external aesthetic results can be adequately evaluated by the surgeon,” unless unique complications with radiologic correlates — bony erosions from impaction of alloplastic silicone prostheses or bone and cartilage autografts, embolization from injection or filler materials, etc. (Fig. 4) — present themselves.

Fig. 4—FLAIR MR image shows filler injection material in right nasolabial fold (arrow).

“Otherwise,” Doo said, “radiologists may typically see incidental uncomplicated postsurgical findings on routine head and neck imaging.”

For more information: www.ajronline.org

Related Content:

Hormone Therapy May Increase Cardiovascular Risk During Gender Transition

Reference

August 09, 2024

August 09, 2024