Figure 1: Example of an intentionally truncated CT image. The truncation percentage was calculated as the ratio of the patient border touching the field of view to the total patient border (red/(read+blue)). Image courtesy of Qaelum.

One of the main benefits of a radiation dose management system is the possibility to automatically generate alerts when the dose exceeds certain thresholds. These dose thresholds are mainly based on national Diagnostic Reference Levels (DRLs), which are defined for a standard-sized patient. An advanced dose management system offers the possibility to automatically select the group of patients by defining a patient size range in terms of weight, effective diameter or Water Equivalent Diameter (WED). As weight is not always filled in, WED, an attenuation-based metric, has become the favourite parameter to indicate patient size. But how accurately is WED calculated? Are we sure that our group of standard-sized patients does not include patients with wrong size calculation? Especially when everything happens automatically, how can we know that a high dose alert does not indicate a bigger patient for whom the size was not correctly calculated?

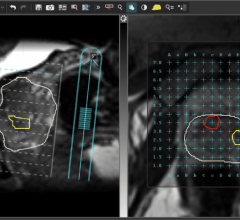

Automatic calculation of WED by a dose management system can be performed from the computed tomography (CT) localizer image or the reconstructed axial images. The difficulty in using the localizer lies mainly in the different calibration of pixel values in terms of water attenuation between vendors/scanner models/software versions, the inclusion of table attenuation, the use of edge-enhancement filters, and the wrong positioning that can magnify or minify the patient’s image. The reconstructed axial CT image is presented as an accurate way to measure the WED of the patient on the condition that the full patient tissue is included in the image.1,2

But what happens if the axial image is truncated? Can it still be used to estimate the WED?

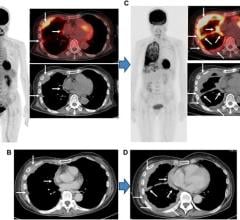

Our research team performed a study to investigate the effect of image truncation on the calculation of water equivalent diameter for chest and abdomen CT scans. We used a set of CT examinations (286 thorax and 222 abdomen CTs) for which the middle slice was not truncated, and then we intentionally truncated the images up to 50 percent (Figure 1). Non-truncated WED values were compared to truncated values.

The results indicated that for truncation percentages below 20 percent, the underestimation of the WED was rather small and no correction was needed. For larger truncation percentages, the difference between the non-truncated and truncated WED became larger, and correction factors3 could improve the calculation of WED. The results were presented at the European Congress of Medical Physics (ECMP 2018)4.

The study was then broadened to evaluate the effect of truncation on the Size Specific Dose Estimates (SSDE) calculation (Figure 2). The results will be presented at the 2019 American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM) annual meeting.

Although defining the Diagnostic Reference Levels for a specific patient size range allows the exclusion of overweight and obese patients, the truncation of the image could lead to a bigger patient being falsely identified as “standard-sized” and generate a dose alert. Knowing the effects of truncation on the calculation can assist in excluding dose alerts from the daily workload.

For more information: www.qaelum.com

References

-

Dedulle et al. Influence of image truncation on the calculation of Water Equivalent Diameter in Computed Tomography examinations. European Congress of Medical Physics, ECMP 2018, 23 – 25 August 2018, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Author's Note: Niki Fitousi, Ph.D., is head of research at Qaelum. An Dedulle is a Ph.D. researcher for Qaelum.

August 09, 2024

August 09, 2024