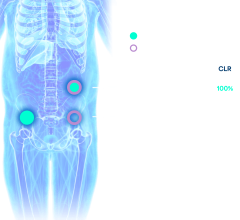

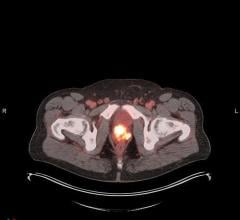

Researchers are using the tracer, which is injected into a patient, then seen with a PET scan, to see if it is possible to diagnose chronic traumatic encephalopathy in living patients. In this image, warmer colors indicate a higher concentration of the tracer, which binds to abnormal proteins in the brain. Credit UCLA Health.

August 24, 2018 — In a small study of military personnel who had suffered head trauma and had reported memory and mood problems, researchers found brain changes similar to those seen in retired football players with suspected chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

CTE occurs in people who have had multiple head injuries. Recent studies and headlines have focused on former football players who exhibited symptoms such as depression, confusion and mood swings. In later stages, CTE can lead to symptoms of Alzheimer's disease and other forms of dementia. Currently, CTE can only be diagnosed after death, when examination of brain tissue reveals clumps of a protein called tau, which kills brain cells.

To aid in diagnosing CTE in living individuals, researchers at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) are studying a molecular tracer, called FDDNP, which binds with tau as well as another abnormal protein called amyloid. The tracer, given intravenously, shows up in positron emission tomography (PET) brain scans, pointing to the location and extent of abnormal proteins in the brain.

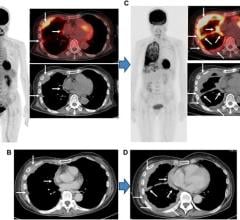

Previously, UCLA researchers used the tracer to study the brains of 15 former National Football League (NFL) players with memory and mood problems. In that study, the pattern of abnormal protein distribution in living patients was consistent with the tau distribution seen in autopsy-confirmed CTE cases.

For the current study, which builds upon the earlier research, seven military personnel (five veterans and two in active duty) who had suffered mild traumatic brain injuries and had memory or mood complaints underwent neuropsychiatric evaluations. They had brain scans after being injected with FDDNP, the molecular tracer. The results were compared to those of the 15 previously studied football players, as well as 24 people with Alzheimer's dementia and 28 people without cognitive problems, for comparison.

The location and quantity of the tracer in the brains of the military personnel were similar to that seen in retired football players and distinct from the distribution patterns seen in people with Alzheimer's disease or in healthy individuals.

Larger studies using FDDNP and brain scans in people at risk for chronic traumatic encephalopathy are needed to confirm the usefulness of FDDNP as a diagnostic tool. The ability to diagnose CTE in living individuals would help scientists observe the progression of the disease, develop treatments and quantify the scope of CTE among different populations, such as military veterans.

Gary Small, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at UCLA and director of the Longevity Center at UCLA's Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, is the study's senior author. The study appears in the July 17 Journal of Alzheimer's Disease.

For more information: www.j-alz.com

Reference

July 30, 2024

July 30, 2024