Greg Freiherr has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service, The Freiherr Group.

Value-based Imaging: A Model For Future Innovation

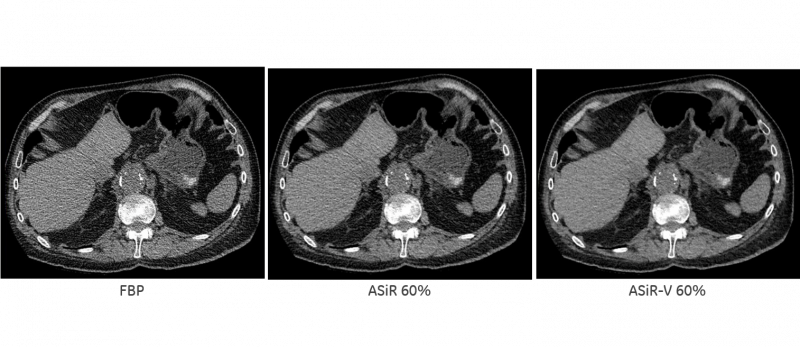

Efficiency and patient comfort both factor into value-based imaging. But it was not the initial reason behind the development of iterative reconstruction. GE Healthcare originally planned to market Adaptive Statistical iterative Reconstruction (ASiR) as the means for improving image quality. The latest version of ASiR is being positioned for its ability to significantly reduce patient radiation dose during CT exams while achieving a reconstruction speed similar to that of conventional analytical reconstruction using filtered back projection. (Graphic from GE Healthcare Image Gallery)

What something does is more important than what it is. This is common knowledge in consumer electronics.

Seventeen years ago, Steve Jobs sold the iPod — not on the product specs of a 5 GB hard drive measuring 1.8-inches — an impressive engineering feat in its own right — but with the claim that it put “1,000 songs in your pocket.” Instead of leading with what the iPod was, Jobs told prospective buyers what it would do for them. He used the specs to support his claim.

The iPod pitch goes back to 2001. But the approach is nothing new. I have described innovations, sometimes half jokingly, as the “best thing since sliced bread,” a cliché rooted in the early 1910s. But sliced bread was not an instant hit. A couple decades passed until it took hold — in the 1930s — amid several claims made by Wonder Bread, which sold its bread not only on it being sliced but that it “builds strong bodies 8 ways.”

Yet, so disruptive was sliced bread that today it is hard to find packaged bread that is not sliced.

Imaging’s Opportunism

Historically the makers of imaging equipment have been content to focus on their products. During the computed tomography (CT) slice wars, vendors upped the “slice” ante every 12 or 18 months. It started with 4 slices; took an interim step to 8; went to 16; took another interim step to 32; then rose to 64, which remarkably is now the high end of low-tier CT scanning.

What was the significance of each successive generation? Certainly not productivity. If presented in the context of throughput, the several seconds saved from one CT generation to the next hardly mattered, considering that techs spend minutes prepping patients. Similarly, reduced cooling times for X-ray tubes — specs worthy of note for the engineering that went into them — meant little in themselves.

But faster scan times and quicker tube cooling allowed more whole body scans in a busy emergency room. Together they could move patients through triage to treatment and, ultimately, improve patient satisfaction, safety, convenience and comfort — perhaps even outcome. But these metrics were hard to document. Vendors have found it easier to shape claims around engineering prowess.

The same was true for scanners delivering 512 or more slices per rotation. They eliminated motion artifacts when imaging the heart and made brain scans more exact. But what effect did they have on the patient? Could a scan done with one of these CTs increase the chance that Dad would come home after a stroke in much the same condition he was before the stroke or heart attack? I didn’t hear that argument when new, top-flight systems were unveiled. What I heard were the engineering specs.

For sliced bread to take hold, it had to be part of something bigger, something that connected with buyers; something that promised to make them … healthier. A major selling point for CT scanners was (and is) how they affect patients.

Style and Substance

This is not about style over substance; not about sizzle over steak. This is about speaking the language of the customer; resonating with needs; being in touch with the market.

Vendors have occasionally fallen in line with this thinking, but it’s been ad hoc. It certainly has not been a driving force behind product development. Take open magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for example. The makers of MR scanners were struggling in the mid-1990s, until open midfield scanners came into vogue. It was patients who propelled midfield opens into the mainstream.

Recognizing that high-field scanning contributed substantially to high-quality imaging, vendors launched major efforts to develop high-field opens. Then they realized that scanners didn’t have to be open, just roomy. Given the difficulty and expense of creating open scanners that operate at truly high fields, the short, wide-bore scanner was born.

Vendors began talking up the comfort benefits for the patient and the “footprint” advantages of these scanners. The less space required, the easier the siting — and the more floor space for other uses. Today every major MR vendor offers short-, wide-bore scanners; all allude to the more spacious experience for patients.

In short, paying attention to what the product can do for the customer (and the patient is the ultimate customer) versus what a technology does can make a huge difference. This is what value-based imaging is all about. And it is what makes value-based imaging the ideal foundation for product models.

Value-based imaging focuses on efficiency, cost-effectiveness and patient satisfaction. Developing products that improve the practice of radiology in these ways could be the cornerstone of a business model, one that spurs the development of needed products rather than rationalizes ones that are already developed.

Opportunism has been the de facto marketing model for original equipment manufacturers. OEMs have tended to develop and make what their engineers have shown was possible, then wrapped those developments in what the market demanded. Iterative reconstruction (IR) is an example. First positioned as a way to improve CT image quality, IR was later — and to this day continues to be — marketed as a way to reduce radiation dosage while maintaining image quality.

Shifting To Value

Like miners following veins of gold serendipitously found, OEMs mine technological veins created by their engineers. Why not implement business models to create what providers and patients need?

Creating such “win-win” situations will not only change how a company acts but what it is. In turn, being the right company for the future will drive the right actions. Business models resulting from such thinking will provide the foundation. These models, built on the needs of the customer, will create long runways onto which ideas can be landed.

Value-based imaging is made to order for this. It is intended to deliver value to the patient and, consequently, to the provider. Moreover, it provides a framework in which OEMs can plan for the future; radiology can evolve, and health care can improve.

April 14, 2025

April 14, 2025