January 2, 2018 — Information from brain magnetic resonance images (MRIs) can help identify people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and distinguish among subtypes of the condition, according to a study appearing online in the journal Radiology.

ADHD is a disorder of the brain characterized by periods of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsive behavior. The disorder affects 5 to 7 percent of children and adolescents worldwide, according to the ADHD Institute. The three primary subtypes of ADHD are predominantly inattentive, predominantly hyperactive/impulsive, and a combination of inattentive and hyperactive.

While clinical diagnosis and subtyping of ADHD is currently based on reported symptoms, psychoradiology, which applies imaging data analysis to mental health and neurological conditions, has emerged in recent years as a promising tool for helping to clarify diagnoses.

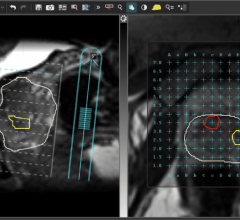

Study co-author Qiyong Gong, M.D., Ph.D., and colleagues at West China Hospital of Sichuan University in Chengdu, China, recently introduced an analytical framework for psychoradiology that involves cerebral radiomics — the extraction of a large amount of quantitative information from digital imaging features that can be mined for disease characteristics. Radiomics, combined with other patient characteristics, could improve diagnostic power and help speed appropriate treatment to patients.

“The main aim of the current study was to establish classification models that can assist the psychiatrist or clinical psychologist in diagnosing and subtyping of ADHD based on relevant radiomics signatures,” Gong said.

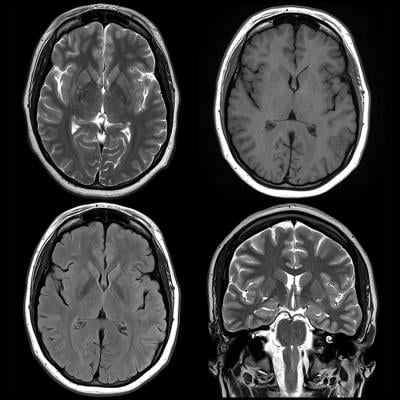

With the help of his West China Hospital colleagues Huaiqiang Sun, Ph.D., and Ying Chen, M.D., Ph.D., Gong studied 83 children, ranging in age from of 7 to 14, with newly diagnosed and never-treated ADHD. The group included children with the inattentive ADHD subtype and the combined subtype. Researchers compared brain MRI results with those of a control group of 87 healthy, similarly aged children. The researchers used a relatively new feature that allowed them to screen relevant radiomics signatures from more than 3,100 quantitative features extracted from the gray and white matter.

No overall difference was found between ADHD and controls in total brain volume or total gray and white matter volumes. However, differences emerged when the researchers looked at specific regions within the brain. Alterations in the shape of three brain regions (left temporal lobe, bilateral cuneus and areas around left central sulcus) contributed significantly to distinguishing ADHD from typically developing controls.

Within the ADHD population, features involved in the default mode network — a network of brain regions active when an individual is not engaged in a specific task — and the insular cortex — an area with diverse functions related to emotion — significantly contributed to discriminating the ADHD inattentive subtype from the combined subtype.

Overall, the radiomics signatures allowed discrimination of ADHD patients and healthy control children with 74 percent accuracy and discrimination of ADHD inattentive and ADHD combined subtypes with 80 percent accuracy.

“This imaging-based classification model could be an objective adjunct to facilitate better clinical decision making,” Gong said. “Additionally, the present study adds to the developing field of psychoradiology, which seems primed to play a major clinical role in guiding diagnostic and treatment planning decisions in patients with psychiatric disorders.”

The researchers plan to recruit more newly diagnosed ADHD patients to validate the results and learn more about imaging-based classification. They also intend to apply the analytic approach to other mental or neurological disorders and test its feasibility in a clinical environment, where the fully automatic analytic framework can be readily deployed, Gong said.

For more information: www.pubs.rsna.org/journal/radiology

July 25, 2024

July 25, 2024