August 22, 2017 — A new UCLA study is the first to identify patient and tumor characteristics that predict the successful creation of models and which types of sarcomas are most likely to grow as xenografts. The research, which is the first and largest patient-derived orthopedic xenograft (PDOX) study in sarcoma, gives physician-scientists a much-needed roadmap for personalizing therapies for the disease without placing patients at risk for treatment-related complications or ineffective therapy.

Sarcoma is a rare and deadly form of cancer occurring in the bones and connective tissue that affects individuals of all ages. Its aggressiveness, rarity and diversity continue to hinder efforts to identify effective therapies for people with this malignancy. PDOXs are unique models where a patient's individual tumor is grown in mice. Such xenografts have long shown great promise in modeling how sarcoma and other cancers can respond to and resist therapies, but their feasibility for use in individual patients in clinical settings remains unknown.

There are up to 50 types of soft-tissue sarcomas, making each type rare. Consequently, it is challenging for scientists to design clinical trials to identify effective systemic treatments, such as chemotherapy or targeted therapy.

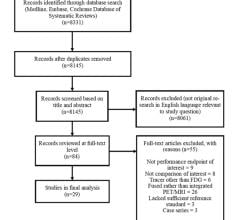

Recent research has shown that PDOXs faithfully reproduce the biological behavior of the human tumor, including treatment response and resistance that accurately mirrors that of the individual patient. Given the overall promise of PDOX, the UCLA team set out to assess the feasibility of generating individual patient PDOX models in a clinical setting and to determine potential factors that facilitate or prevent the successful development of xenografts from people with sarcomas.

In the yearlong study, the UCLA team collected tumor samples from 107 people with soft-tissue sarcomas. Tumor fragments were then surgically implanted into the mice in the anatomic site corresponding to the original tumor location in the patient. The researchers assessed the ability of the models to successfully "establish," meaning that after implantation of the human tumor fragments in the mouse model, a new tumor grew. The tumor fragments could also be subsequently transferred and grown in additional mice for further testing, said Fritz Eilber, M.D., professor of surgery, Division of Surgical Oncology and chief of the Cancer Surgery Service at UCLA, and the senior author of the study.

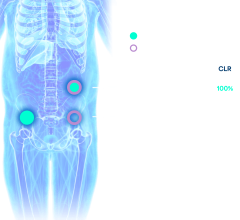

Eilber and colleagues discovered that only the aggressive, or high-grade, tumors established but not the less aggressive, or low-grade, sarcomas. Of the high-grade tumors that did establish, the highest rates (62 percent) were from people whose tumors had not previously been treated with chemotherapy or radiation. Tumors from people who had undergone pre-operative radiation therapy for their sarcoma saw no successful establishment of PDOX models, and establishment was also lower when patients had received pre-operative chemotherapy (32 percent) compared with those who had untreated tumors.

PDOX establishment rates were as high as 86 percent in some subtypes of untreated aggressive sarcomas and the median time to establishment was 53 days.

The study demonstrates that patient-derived orthotopic xenografts are feasible for use in the clinical setting and can provide oncologists with a roadmap to accurately identify which patients will and will not benefit from a specific therapy. This research has the potential to change the way that people with sarcoma and other cancers are treated.

UCLA researchers are conducting additional studies to learn if individual patient PDOX models can be developed for needle biopsies, as well as determining the potential of PDOX models to guide patient therapy and outcomes.

The research was published online Aug. 2 in JCO Precision Oncology.

For more information: www.ascopubs.org/journal/po

August 09, 2024

August 09, 2024