February 1, 2017 — Too little sleep takes a toll on your heart, according to a new study presented at the 2016 annual meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA), Nov. 27-Dec. 1 in Chicago.

People who work in fire and emergency medical services, medical residencies and other high-stress jobs are often called upon to work 24-hour shifts with little opportunity for sleep. While it is known that extreme fatigue can affect many physical, cognitive and emotional processes, this is the first study to examine how working a 24-hour shift specifically affects cardiac function.

"For the first time, we have shown that short-term sleep deprivation in the context of 24-hour shifts can lead to a significant increase in cardiac contractility, blood pressure and heart rate," said study author Daniel Kuetting, M.D., from the Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology at the University of Bonn in Bonn, Germany.

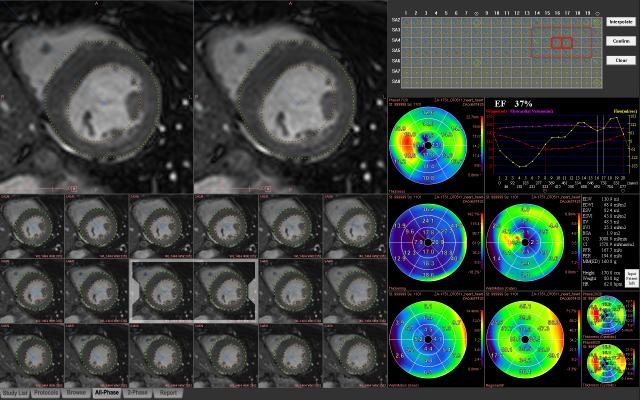

For the study, Kuetting and colleagues recruited 20 healthy radiologists, including 19 men and one woman, with a mean age of 31.6 years. Each of the study participants underwent cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging with strain analysis before and after a 24-hour shift with an average of three hours of sleep.

"Cardiac function in the context of sleep deprivation has not previously been investigated with CMR strain analysis, the most sensitive parameter of cardiac contractility," Kuetting said.

The researchers also collected blood and urine samples from the participants and measured blood pressure and heart rate.

Following short-term sleep deprivation, the participants showed significant increases in mean peak systolic strain (pre = -21.9; post = -23.4), systolic (112.8; 118.5) and diastolic (62.9; 69.2) blood pressure and heart rate (63.0; 68.9). In addition, the participants had significant increases in levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), thyroid hormones FT3 and FT4, and cortisol, a hormone released by the body in response to stress.

Although the researchers were able to perform follow-up examinations on half of the participants after regular sleep, Kuetting noted that further study in a larger cohort is needed to determine possible long-term effects of sleep loss.

"The study was designed to investigate real-life work-related sleep deprivation," Kuetting said. "While the participants were not permitted to consume caffeine or food and beverages containing theobromine, such as chocolate, nuts or tea, we did not take into account factors like individual stress level or environmental stimuli."

As people continue to work longer hours or work at more than one job to make ends meet, it is critical to investigate the detrimental effects of too much work and not enough sleep. Kuetting believes the results of this pilot study are transferable to other professions in which long periods of uninterrupted labor are common.

"These findings may help us better understand how workload and shift duration affect public health," he said.

Co-authors on the study are Andreas Feisst, M.D., Rami Homsi, M.D., Julian A. Luetkens, M.D., Daniel Thomas, M.D., Ph.D., Hans H. Schild, M.D., and Darius Dabir, M.D.

For more information: www.rsna.org

December 10, 2025

December 10, 2025