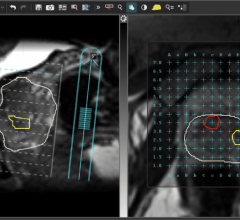

Example of the iDISCO technique to image brain samples containing Alzheimer’s disease, which could have major impact on treatment. For more inages and videos view the article online at www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(16)30814-2

August 30, 2016 — Rockefeller University researchers have used a recently-developed imaging technique that makes tissue transparent to visualize brain tissue from deceased patients with Alzheimer's disease. The technique has exposed nonrandom, higher-order structures of beta amyloid plaques — sticky clumps of a toxic protein typically found in the brains of people with Alzheimer's. The findings were published online July 14 in Cell Reports.

"Until now, we've been studying the brain using 2-D slices; and I've always felt that was inadequate, because it's a complex, 3-D structure with many interlocking components," said senior author Marc Flajolet, an assistant professor in the Laboratory of Molecular and Cellular Neuroscience at The Rockefeller University. "Not only was slicing time-consuming and 3-D reconstruction laborious when not erroneous, it gave us a limited view. We needed some way to look at this 3-D structure in all of its dimensions without preliminary slicing of the brain."

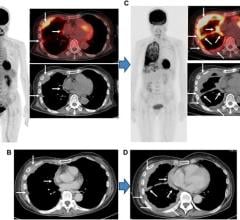

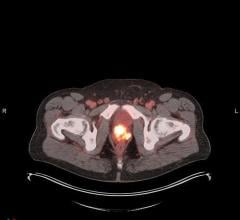

The researchers wanted to go beyond the traditional 3-D brain imaging (e.g., positron emission tomography [PET] or functional magnetic resonance imaging [fMRI] scans), which show brain activity in a broad way but have a low resolution overall. To circumvent this, the research team turned to a recently developed method, called "iDISCO." Here, brains are soaked in a solution that imbues the fats within it with a charge, before being exposed to an electrical field with an opposite charge, which behaves like a magnet, forcing all of the fat out of the brain tissue.

The result, said Flajolet, is a brain that is hard and transparent, almost "like glass," which allowed the researchers to see the amyloid plaques in full detail and in 3-D, in a full mouse brain hemisphere, as well as in small blocks of human brain tissue.

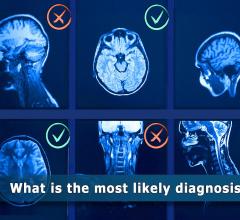

"In mouse models, plaques are rather small, homogenous in size and shape, and not grouped in any specific way," said Flajolet. "But in the human brain, we were seeing more heterogeneity, larger plaques and these new, complex patterns." These structures, called three-dimensional amyloid patterns (TAPs) may have implications for the future of Alzheimer's disease treatment, he said. By comparing doctor's reports of a patient's symptoms with images of the patient's brain post-mortem, they may be able to classify different categories of Alzheimer's disease.

"There are people with brains full of plaques and no dementia at all," he said, "and there are those with brains free of plaques with many of the symptoms." In light of that, the way that current clinical trials view the disease — namely, that there is one category —might be incorrect, he said. It is possible that current drugs may be beneficial only for a subset of Alzheimer patients, but we have no way to distinguish them at this day.

Flajolet stressed that, moving forward, we need a better understanding of these plaques, and Alzheimer's hallmarks in general, as the relationship between their presence and the severity of the disease is not clear-cut. "Perhaps this will lead to the development of new and better targeted drugs, or allow us to rethink the drugs we have now — that's what we hope for,” he said.

This work was supported, in part, by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the Fisher Center for Alzheimer's Research Foundation, and the Cure Alzheimer's Fund. Additional support was received from the Empire State Stem Cell Fund through the New York State Department of Health.

For more information: www.cell.com/cell-reports

July 30, 2024

July 30, 2024