University of Oklahoma professors Bin Zheng, Ph.D., (left) and Hong Liu, Ph.D., are developing innovative imaging technology and quantitative image processing methods to significantly improve efficacy of breast cancer screening. (Photo courtesy of Hugh scott, University of Oklahoma)

The fight against breast cancer has been a highly visible campaign for several decades, with numerous high-profile charities, research groups and celebrity cases helping shine a large spotlight on one of the most frequently diagnosed forms of cancer. Aside from working to find a cure, a large part of the conversation has focused on how to most accurately determine who is at high risk for contracting the disease.

Actress Angelina Jolie generated a large amount of buzz in May 2013 when she announced that she had undergone a double mastectomy. She elected to have the surgery because she had tested positive for the BRCA1 genetic mutation, a factor that greatly increased her risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer.

Jolie’s announcement sparked a documented increase in interest about genetic testing in the public: A survey put out a few days later by a North Carolina State University researcher found that out of 229 female participants, 30 percent said they intended to get tested for the BRCA1 gene mutation. A second study, presented at the 2014 Breast Cancer Symposium in San Francisco, concluded the announcement likely doubled genetic referrals, testing and detection of BRCA mutation carriers over a six-month period at a Canadian academic center.

This kind of surge leads to the question, however, of whether genetic testing is appropriate for that large a number of people. It is, after all, just one method for assessing breast cancer risk, and each has its merits. Conversations such as these, however, are pushing innovators to take a closer look at how risk levels are determined and how the science can be refined.

Genetic Testing

Genetic testing for the BRCA mutation has been part of cancer risk assessment since the mid-1990s, according to Kristie Bobolis, M.D., a hematology and oncology specialist at Sutter Roseville Medical Center in Roseville, Calif., and the program chair for the National Consortium of Breast Centers (NCBC). In the ensuing years, however, researchers have continued to discover more genes, both high- and intermediate-risk, that could be potential warning signs, leading to the development of genetic panels that can test for multiple gene mutations simultaneously. The side effect of this evolution, said Bobolis, is that testing has become more complex for both physicians and patients.

The increased versatility of these tests, combined with stories like that of Angelina Jolie, have made the idea of universal genetic testing for breast cancer a hot topic of debate. In a 2014 study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), Mary-Claire King, Ph.D., professor of genome sciences and medicine (medical genetics) at the University of Washington, Seattle, suggested such a program was needed in the United States. King and a colleague in Israel conducted a study of that country’s Ashkenazi Jewish population, where 1 in 50 women carry a harmful BRCA mutation and

90 percent of breast cancer cases can be attributed to the anomaly. The study also tested Ashkenazi Jewish men, as they have an equal opportunity to inherit and pass on the gene to their children. This method allowed researchers to detect a large number of individuals, both male and female, at high risk irrespective of a woman’s personal or family history of cancer. In an accompanying opinion piece, King suggested that similar population screening should be conducted on all women in the United States beginning at age 30.

Elisa Long, Ph.D., assistant professor in decisions, operations and technology management at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), read the study and wanted to test the feasibility of King’s proposal, so she teamed up with Patricia Ganz, M.D., director of the division of cancer prevention and control research at UCLA’s Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, to crunch the numbers.

According to Ganz, unlike in the Ashkenazi Jewish population, BRCA gene mutations only account for 5-10 percent of the 233,000 new breast cancer cases annually in the United States. Furthermore, the most widely used genetic test (offered by Myriad Genetics) sells for approximately $4,000 per test. Using those numbers, they determined that universal screening would cost $1-2 million to detect a single BRCA mutation.

“Even though you may test everyone in the population, you’re only going to find a small number — around 0.025 percent — who are likely to be carriers, and all of the other women you test will still be at risk for breast cancer,” she said.

Ganz still believes that universal genetic testing could be possible one day, but said the cost of BRCA screening would need to drop by 90 percent before that vision could be achieved. “I think we could get to that point, though,” she stated.

A large part of the reason costs were so prohibitively high is that Myriad Genetics had been the first to clone the BRCA gene sequence in the 1990s and had patented the sequence. The patent was invalidated by the U.S. Supreme Court in a June 2013 ruling. Since then, new products have started to emerge, including a $249 BRCA test recently announced by Color Genomics.

Further complicating the economic feasibility of genetic testing, Medicare reimbursement and insurance coverage of the tests has fluctuated in recent years. In 2013, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) set the maximum reimbursement rate for BRCA1 and 2 testing at $2,795. The 2014 maximum rate was $1,440 —

a 49 percent reduction from the previous year.

Setting the Bar for MRI

While genetic testing has received much of the spotlight, breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has also been expanding its versatility as a risk assessment tool.

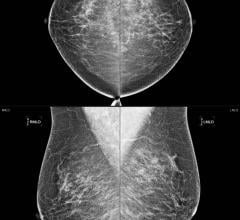

One of the primary advantages breast MRI has over conventional mammography is its ability to see through dense fibroglandular breast tissue, detecting cancers that might be hidden on a mammogram. Dense breast tissue increases a woman’s risk of breast cancer all by itself — and yet, many risk assessment models do not figure density into their calculations, according to Alan Hollingsworth, M.D., medical director of the Mercy Breast Center in Oklahoma City. “We’ve known that mammographic density is a risk factor, and yet it took 20 years to get it integrated into certain models we use on patients, and most people still aren’t using those models,” he said.

Today, patient selection for breast MRI screening is based on guidelines issued by the American Cancer Society (ACS) in 2007. Under the guidelines, MRI is recommended for patients at high risk of developing breast cancer, with “high risk” defined as a 20-25 percent or greater lifetime risk under the BRCAPRO model and other mathematical models. For patients just below that level, in the 15-20 percent range, ACS said there was insufficient evidence to recommend for or against MRI screening.

What the guidelines do not consider is that the majority of patients fall into that second-tier category, as approximately 80 percent of patients who develop breast cancer do so without exhibiting any of the risk factors typically used to calculate risk levels. Furthermore, according to Hollingsworth, even among those who do qualify as high-risk and are eligible for MRI screening, the cancer yield will only be 3-4 percent. “So women with dense breasts were in double jeopardy — they had a higher risk, even though it was modest, and also it was more likely it was going to be missed on the mammogram,” he said.

Hollingsworth and Mercy radiologist Rebecca Stough, M.D., assessed the effectiveness of the ACS guidelines in a study published in the March/April 2014 edition of The Breast Journal. Out of 1,643 breast MRIs conducted between July 2004 and December 2011, a total of 33 malignancies were discovered. Under the ACS guidelines, only 15 of the 33 would have met the 20-25 percent lifetime risk threshold to be recommended for breast MRI.

“Risk-based screening has reached its limit. It can’t get any better,” Hollingsworth said.

Building a New Model

In order for breast MRI to become a more effective tool for breast cancer risk assessment, Hollingsworth believes a new model has to be created incorporating factors like breast density. That is why he has joined forces with two researchers at the University of Oklahoma who are developing a computer-aided technique that could increase the number of patients who could benefit from breast MRI screening.

The model in question — being developed by Hong Liu, Ph.D., director of the Center for Advanced Medical Imaging, and Bin Zheng, Ph.D. — utilizes computer-aided detection (CAD) to assess imaging features of both mammograms and MRI scans. Such technology is already in use, but the Oklahoma model is looking for bilateral asymmetry of two new, specific factors — namely, mammographic density and background parenchymal enhancement (BPE). By putting these two factors in the hands of a computer, they can also reduce subjective variability between observers. As a result, said Zheng, “We should be able to predict the risk of harboring mammography-occult cancer at an early stage.”

For Hollingsworth, the idea was intriguing. “They had identified women at very high short-term risk — the risk was nine- and tenfold in relative terms — and if you’ve got risk that high that’s short-term, you’ve got to ask yourself, is it really not risk but are they identifying early cancers there,” he said. “They’re seeing the very first signs of cancer through this computerized image analysis. So I said I’d love to do MRIs on those people.”

Hollingsworth followed up, and in late August the group received a $2.5 million grant from the National Cancer Institute to conduct initial research. The grant has four primary objectives:

• A retrospective study of 4,000-5,000 mammograms, assessing density and BPE to rule-in patients for MRI screening;

• A similar prospective rule-in study;

• A rule-out study of approximately 500 patients already receiving breast MRI exams to determine efficiency and how often they need to be screened; and

• Building a risk assessment model that factors in fibroglandular density and MRI enhancement patterns in addition to traditional risk factors.

Hollingsworth hopes that over the course of the five-year study, the cancer detection yield rate can be increased from 3-4 percent up to 10 percent, “which would be vastly more cost-effective than we’re selecting patients for MRI today,” he said.

Whether through MRI, genetic testing or other models, risk assessment is key to breast cancer screening, prevention and treatment. While traditional models and the epidemiological risk factors that inform them are still relevant, new discoveries necessitate a shift in thinking, which the new models and methods discussed are working to implement. In the words of Zheng, the idea is not to replace the existing models, but to provide supplemental information so that providers and patients can make the most informed decisions about their healthcare.

July 29, 2024

July 29, 2024