July 31, 2015 — Researchers at the University of Kentucky’s Sanders-Brown Center on Aging are on the hunt for biomarkers that might serve as an early warning system for Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Although the term didn’t surface until the 1980s, the concept of biomarkers has been around for almost a century. Today, doctors routinely test blood for signs of anemia or the antigen associated with prostate cancer. Urine samples can hint at the presence of infection or diabetes, and EEGs diagnose electrical abnormalities in the brain.

But scientists are now advancing the concept, looking for ways to identify a host of diseases early in the process to provide opportunity for early intervention and improve the chances that treatment will be effective.

This is particularly true for AD, where evidence points to the fact that the disease process begins long before someone has clinical symptoms, and the ramifications of the disease – both financial and emotional – are disastrous.

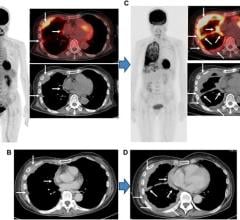

According to Mark Lovell, Ph.D., Jack and Linda Gill Professor of Chemistry, the only definitive way to diagnose AD is through autopsy; other options, such as positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, are becoming more widely used to identify the presence of AD pathology. The challenge, he explained, is finding a biomarker that is an accepted predictor of the disease and can easily be identified by a physician at the clinic level.

“Multiple studies show alterations in levels of the proteins associated with AD – tau and beta amyloid-- in cerebrospinal fluid, but a spinal tap to obtain that fluid is often a hard sell for patients”, Lovell said. “Furthermore, there appears to be variability in the data connecting the levels of these proteins in CSF and the diagnosis of AD, which has limited the use of beta amyloid and tau clinically."

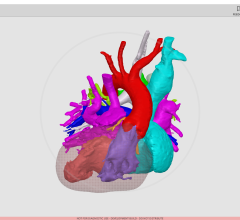

Working with Bert Lynn, Ph.D., director of UK’s Mass Spectrometry Center, Lovell began to sort proteins in CSF samples by weight. As the results came in, two particular proteins (transthyretin and prostaglandin-d-synthase) caught his attention.

“We were able to tease out that these two proteins, when subjected to oxidative damage, tended to stick together and fractionate at a higher molecular weight than expected,” said Lovell.

Further study suggested these proteins may signal dysfunction in the choroid plexus, a brain region responsible for the production and filtration of cerebrospinal fluid.

Since, in AD, current data suggest there are changes in the transfer capacity of the choroid plexus it made sense to Lovell and Lynn that these two proteins might make a good biomarker for AD.

The next step, said Lovell, was to go “downstream”—to blood or urine, for example– to determine whether this same protein combination appears there as well.

“I’ve historically been skeptical that blood can be as strong a predictor of Alzheimer’s disease as CSF, but I was pleasantly surprised to see that there was a reasonable correlation in samples of CSF and blood taken from the same patients,” Lovell said.

Lovell cautions that further evaluation in larger sample populations is necessary before this can be called a definitive success, but if the hypothesis is borne out, “we will have a blood-based biomarker that might be more predictive than amyloid beta peptide.”

Ultimately, Lovell thinks AD will be diagnosed by a panel of three or four biomarkers, rather than a single “up or down” test. And that’s where Brian Gold comes in.

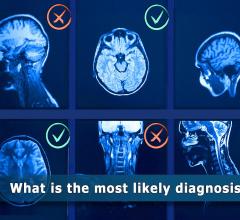

Gold, a cognitive neuroscientist, is fascinated by CSF protein biomarker findings of Lovell and others and is conducting his own research in the hopes of using brain imaging to find non-invasive AD biomarkers. However, up until now, Gold explains, most magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies of preclinical AD have been restricted to structural volumetric characteristics of the brain.

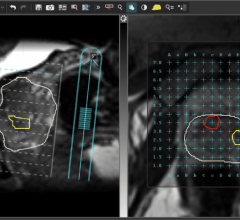

“We’ve instead been focusing on microstructural brain changes detectable with a form of MRI called diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), which assesses the diffusion of water molecules in the brain," said Gold. "As cellular structures begin to degenerate, tissue barriers degenerate as well, allowing for increased water diffusion. DTI-based changes in the brain are thus somewhat analogous to hairline cracks in a house’s foundation that precede visible structural damage.”

Gold and his colleagues are one of just a handful of U.S. groups exploring how CSF protein biomarkers correlate with microstructural brain changes using DTI and dynamic physiological changes using functional MRI.

His work, published last year in the Neurobiology of Aging, found tantalizing correlations between reduced white matter microstructure in the brain and the presence of CSF markers of AD.

“In other words, if our findings using DTI and functional MRI are highly correlated with Lovell’s CSF biomarkers, we have potentially uncovered a minimally invasive way to diagnose pre-clinical AD.”

For more information: www.centeronaging.uky.edu

July 25, 2024

July 25, 2024