February 23, 2015 — Researchers at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) have found that radiation therapy is the most common treatment for men with prostate cancer regardless of the aggressiveness of the tumor, risk to the patient and overall patient prognosis. These findings lay the groundwork for improved treatment assessment by physicians and to better inform men fighting the disease.

Led by UCLA Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center member Karim Chamie, M.D., the observational study analyzed the claims data of more than 37,000 patients from 2004 to 2007, provided by the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The study was published online in the journal JAMA Oncology.

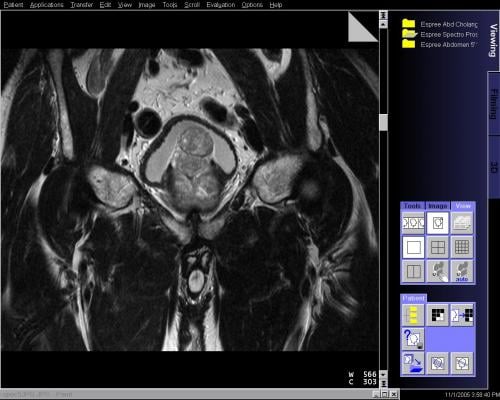

The research was conducted at UCLA, and Chamie's team found that radiation therapy was the most common treatment at 58 percent, followed by radical prostatectomy (a surgical procedure to remove the prostate) at 19 percent. Other treatments trailed at 10 percent, including watchful waiting (where doctors wait and see if cancer progresses before treating it) and active surveillance (when patients undergo routine biopsies, blood tests and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI] to determine if cancer is progressing and undergo active treatment).

Chamie and colleagues discovered that radiation was the most common treatment prescribed regardless of cancer stage, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, cancer grade or the life expectancy of the patient. The most significant predictor of a man receiving radiation therapy is a referral to a radiation oncologist. On the other hand, urologists and surgeons significantly incorporated the age and health of the patient as well as the aggressiveness of the cancer when recommending surgery.

"Doctors and patients view radiation as safe," said Chamie, associate professor of urology. "There's no anesthesia or hospitalization, the patient comes in for 15 or 20 minutes for their daily radiation treatment, it's localized to a specific area, then they get to go home. They often don't notice any immediate effects upfront."

But by two years after treatment, men often start to suffer side effects, said Chamie. These side effects may vary from being mild in nature to very severe.

If a patient has an aggressive prostate cancer and has a long life expectancy, then these side effects and risks may be significantly outweighed by the benefits of the radiation treatment. However, if a man with an indolent prostate tumor and a limited life expectancy is treated with radiation therapy and suffers from these side effects during the twilight of his life, then he reaps no benefit and only suffers from the toxicity.

Chamie hopes these findings enlighten the public and allow physicians to make an informed decision when it comes to the best treatment option for men who may or may not benefit from radiation therapy in the long run.

"Men fighting this disease don't always need radiation or surgery as their only choice," said Chamie. "As we find more reports demonstrating the safety and efficacy of active surveillance, I hope patients and physicians look to this as the first treatment option for low-risk and indolent disease. Here at UCLA, I am proud to say that we have a robust active surveillance program that utilizes MRI and targeted biopsies to monitor and survey these indolent tumors."

For more information: www.cancer.ucla.edu

December 11, 2025

December 11, 2025