June 16, 2014 — Children with heart disease are exposed to low levels of radiation during X-rays, which do not significantly raise their lifetime cancer risk. However, children who undergo repeated complex imaging tests that deliver higher doses of radiation may have a slightly increased lifetime risk of cancer, according to researchers at Duke Medicine. The findings, published June 9 in the American Heart Association (AHA) journal Circulation, represent the largest study of cumulative radiation doses in children with heart disease and associated predictions of lifetime cancer risk.

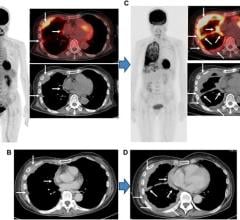

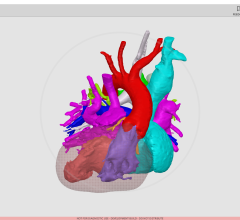

Children with heart disease frequently undergo imaging tests, including X-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans and cardiac catheterization procedures. The number of imaging studies patients are exposed to depends on the complexity of their disease, with more serious heart conditions typically requiring more testing.

Although children benefit from advanced imaging procedures for more accurate diagnosis and less invasive treatment, the increase in radiation has potential health risks.

“In general, the benefits of imaging far outweigh the risks of radiation exposure, which on a per study basis are low,” said senior author Kevin D. Hill, M.D., M.S., an interventional cardiologist and assistant professor of pediatrics at Duke University School of Medicine. “We know that each of these individual tests carries a small amount of risk, but for patients who get frequent studies as part of their care, we wanted to better understand the risk associated with repeated exposure.”

Hill and his colleagues studied a group of 337 children ages six and younger who had one or more surgeries for heart disease from 2005 to 2010. During the five-year study period, the children received an average of 17 imaging tests each as part of their medical care before and after their surgeries.

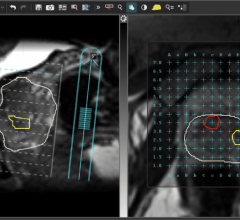

In order to estimate the amount of radiation delivered in the tests, the researchers used a combination of existing data on radiation levels, as well as simulations that calculated radiation doses using child-sized “phantoms,” or models to estimate radiation exposure.

The researchers found that most children had low exposure to radiation, amounting to less than the annual background exposure in the United States. However, certain groups of children, particularly those with more complex heart disease, were exposed to higher cumulative doses from repeated tests and high-exposure imaging.

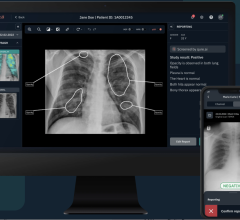

Abdominal and chest X-rays accounted for 92 percent of the imaging tests, but only 19 percent of the radiation exposure. Advanced imaging (CT and catheterization) made up only 8 percent of imaging tests performed, but accounted for 81 percent of radiation exposure.

The researchers estimated the average increase in lifetime cancer risk to be 0.07 percent, with the risk increase ranging from 0.002 percent for chest X-rays to 0.4 percent for complex imaging.

“Clinicians need to weigh the risks and benefits of different imaging studies, including those with higher radiation exposure,” Hill said. “We’re not proposing eliminating complex imaging – in fact, they’re critically important to patients – but we can make significant improvements by prioritizing tests and simply recognizing the importance of reducing radiation exposure in children.

The researchers also noted that lifetime cancer risk was increased among girls and children who had imaging tests done at very young ages. Girls had double the cancer risk of boys because of their increased chances of developing breast and thyroid cancers.

In addition to Hill, authors include Jason Johnson, Christoph Hornik, Jennifer Li, Daniel Benjamin Jr., Terry Yoshizumi, Robert Reiman and Donald Frush. The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (UL1TR001117) and the Mend a Heart Foundation.

For more information: www.dukemedicine.org

August 09, 2024

August 09, 2024