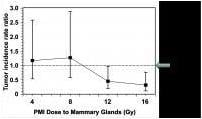

Breast-cancer rates in breast cancer-prone mice whose mammary glands were treated with different doses of prophylactic mammary irradiation (PMI), compared with mice whose mammary glands were not treated.

January 31, 2014 — Survivors of breast cancer have a one in six chance of developing breast cancer in the other breast. But a study conducted in mice suggests that survivors can dramatically reduce that risk through treatment with moderate doses of radiation to the unaffected breast at the same time that they receive radiation therapy to their affected breast. The treatment, if it works as well in humans as in mice, could prevent tens of thousands of second breast cancers. PLOS ONE published the study, which was conducted by researchers at Columbia University Medical Center (CUMC) and led by David J. Brenner, Ph.D., director of CUMC's Center for Radiological Research and the Higgins Professor of Radiation Biophysics.

The idea for prophylactic mammary irradiation (PMI) of the unaffected breast stems from an earlier study of standard whole-breast irradiation after lumpectomy. In that study, Brenner found radiation is highly effective at killing premalignant cells. Those cells could be located in any quadrant of the breast, including the other three quadrants where the primary tumor was not located and premalignant cells are generally considered unrelated.

The critical question was whether treating the breast with a moderate dose of radiation would lower the overall risk of a second cancer. "We know that there will be a balance between radiation killing premalignant cells and radiation producing premalignant cells, but it seemed that using the right radiation dose would put the balance strongly toward lowering the cancer risk," Brenner said.

The current study tested this hypothesis by performing PMI on transgenic mice that have a high risk of developing breast cancer, simulating the unaffected breast of a breast cancer survivor. Lead shields were positioned so one side of each mouse was shielded from the radiation. As predicted, a moderate dose of radiation reduced the breast cancer risk in the treated side by a factor of about three.

The researchers are now planning to test PMI in a clinical trial. If PMI proves to be successful in patients, it could be used as an adjunct to tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors and as a standalone therapy for those with estrogen-receptor negative tumors. In either case, PMI could be performed concurrently with radiotherapy of the affected breast.

Brenner plans to next analyze if PMI could benefit women with BRACA1 or BRACA2 mutations.

The paper is titled, "Potential Reduction of Contralateral Second Breast-Cancer Risks by Prophylactic Mammary Irradiation: Validation in a Breast-Cancer-Prone Mouse Model." The other contributors are Igor Shuryak, Lubomir B. Smilenov, and Norman J. Kleiman, all at CUMC.

For more information: www.plosone.com