The world of personal pronouns has changed from when I was a kid. “That” has pushed “who” out of the picture, as in “he’s the patient that is showing signs of …”

It’s a little unsettling. Not that long ago language was very clear, very precise. “Who” was for people; “that” was for things. Like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and its definition of multiple sclerosis (MS).

In the early 1980s, when the value of MRI as a clinical modality was being debated, the visualization of bright spots in the brains of MS patients exemplified what this fledgling technology could do.

Over the years, demyelinization of neurons, as seen with MRI, was recognized not only as a sign of this disease, but as an indicator of patient relapse or remission … even response to therapy. Then came the radiologically isolated syndrome (RIS).

RIS first appeared as an incidental finding. It was identified initially in 2008 as the presence of MRI-defined signs of MS in patients who do not have the clinical expression of the disease. The syndrome was first found in a patient undergoing a brain scan for an indication other than MS. It has since been identified in MS-free individuals who later developed clinical symptoms of the disease.

One might conclude that RIS is preclinical indicator of MS. But why RIS patients do not have symptoms when the radiological signs of disease are clearly evident is not known. Which brings us back to “that.”

The use of “that” is hardly purposeful. Most people, I imagine, don’t think about whether to use “that” or “who” — they just use one or the other and “that” is their choice. This is not so in diagnostic medicine. Diagnosticians are very deliberate. They don’t interpret an MRI out of context. They read it as part of a patient history, which is how RIS was discovered. The electronic medical record (EMR) provides the context in which to draw conclusions. And that may be the saving grace of diagnostic medicine as we move into the future.

As technology evolves, what was once clear-cut is no longer.

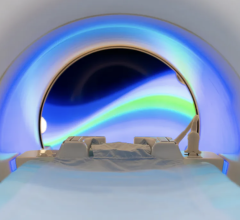

Three Tesla (3.0T), for example, is the new clinical benchmark for MRI. At that field strength, scans deliver extraordinary detail compared to those done at 1.5T. At 7.0T, the images reveal even more detail. There are good reasons why 7.0T will never become a clinical standard, reasons that relate to the health of the patient. But, while an argument can be made that we will never go beyond 3.0T, I’ve learned to “never say never.”

We, therefore, must not only question what we are now seeing with today’s technology, but what it will mean as the technology continues to evolve. Will we see more RIS-like conditions for other diseases — more preclinical signs that may or may not develop into disease? And if we do, how do we make sense of these signs?

The one constant we can be sure about is uncertainty. It is comforting to see how well we have done in our everyday lives.

When Abbott and Costello popularized their “Who’s on First” sketch, “who” was widely used as a personal pronoun. The humor of the sketch was based on the certainty of grammatical conventions. Over the years, humor and grammar have changed. I doubt today that audiences, especially young audiences, would understand the sketch, much less find it funny. But that’s OK. We continue to evolve.

Just as something as engrained as our sense of humor has changed, so will our definition of disease. I feel sure of “that.”

Greg Freiherr has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service, The Freiherr Group. Read more of his views on his blog at www.itnonline.com.

July 25, 2024

July 25, 2024