Greg Freiherr has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service, The Freiherr Group.

Politics of the Breast

When it comes to medical imaging, pick any part of the body other than the female breast and the FDA pays little notice. This particular part of the anatomy gets an extraordinary amount of attention, particularly as it pertains to cancer. Politics has a lot to do with it.

Politicians and their corporate donors seek to sway cancer policy from research to the R&D of specific devices. Breast cancer has a political lobby that flexes its muscles on Capitol Hill to win insurance coverage for diagnostic and even reconstructive procedures following mastectomy. It even has a month – this month – dedicated to its awareness.

Largely, for this reason, the technologies developed to find and treat breast cancer receive special scrutiny in the bureaucracy charged with keeping the public safe. Breast CT is one of those technologies.

After decades of clinical use, CT has been grandfathered into the regulatory fabric. Any CT developer seeking the right to market its product in the U.S. typically needs only a 510(k) clearance. Navigating this process requires a company to simply demonstrate that its new product is “substantially equivalent” to one already on the U.S. market.

In 2006, the Koning Corp. came to the McCormick Center in Chicago brimming with enthusiasm about its breast CT scanner, hopeful that its breast CT would soon be cleared by the FDA. In an interview, two months before the product’s debut at RSNA 2006, company CEO John H. Neugebauer told me he was optimistic that the product would be available in the U.S. before the year was out. (“Breast CT scanner readies for RSNA meeting debut,” Oct. 1, 2006, DiagnosticImaging.com) Five years later the company – and the market – are still waiting.

Koning has persisted in its development of breast CT, having built two pre-production prototypes, one installed at Elizabeth Wende Breast Care in Rochester, N.Y., the other at Emory University in Atlanta, Ga. Both are being used in clinical studies. Koning has since been joined by another company, ZumaTek, a startup founded by researchers from Duke University, who plan to build a clinic-ready CT for use in a clinical trial against digital X-ray mammography. A research team at the University of California, Davis has built two prototypes of its own and is working on a third. The group has already scanned about 500 patients and is planning to ramp up studies.

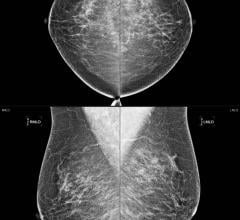

This work has had an enormous impact, raising CT technology to the special challenges of breast imaging with prototypes promising submillimeter spatial resolution and radiation doses equivalent or below those of standard digital mammograms. The importance of these developments cannot be overemphasized.

The special requirements of screening for cancer – to visualize the earliest signs of this disease – tax technology like no others. And, because the breast is scanned periodically, sometimes annually for decades, the women undergoing screening exams are especially vulnerable to the cumulative effects of radiation.

In the years ahead, breast CT may finally become a commercial reality. If it does, women stand to gain much from the accurate and volumetric reconstructions possible with this technology, while paying the minimum possible in exposure to radiation, thanks in part to the politicization of a disease.

July 29, 2024

July 29, 2024