Egyptian Mummies Show Earliest Cases of Coronary Disease on CT

A U.S.-Egyptian research team has uncovered the earliest documented case of coronary atherosclerosis in a princess who died in her early 40s and lived between 1580 and 1550 B.C. Of the other mummies studied – a sampling of the elite in ancient Egypt – almost half showed evidence of atherosclerosis in one or more of their arteries, calling into question our perception of atherosclerosis as a modern disease, according to research presented this week at the American College of Cardiology (ACC) Scientific Session in New Orleans.

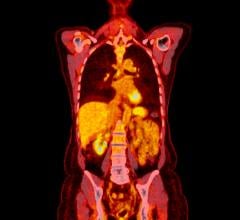

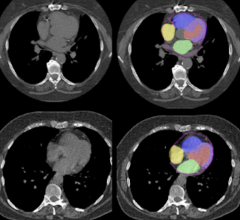

While atherosclerosis has been observed before in ancient Egyptians, this study found it to be more prevalent than previously thought. The interdisciplinary team performed whole body computerized tomography (CT) scans on 52 ancient Egyptian mummies to determine if atherosclerosis was present. Of the 44 with identifiable arteries or hearts, nearly half (45 percent) had calcifications either in the wall of an artery or along the course of an artery that are diagnostic of or highly suggestive of atherosclerosis. “Commonly, we think of coronary artery or heart disease as a consequence of modern lifestyles, mainly because it has increased in developing countries as they become more westernized,” said Gregory S. Thomas, M.D., MPH, clinical professor and director of nuclear cardiology education, University of California, Irvine and the study’s co-principal investigator.

“These data point to a missing link in our understanding of heart disease, and we may not be so different from our ancient ancestors.” Most of the atherosclerosis was found in the large arteries of the body, including the aorta in the abdomen. However, key smaller arteries were also involved. About 7 percent of the mummies had obstructions in the heart arteries, and 14 percent had blockages in the arteries to the brain, the carotid arteries, which is a leading cause of stroke in the present day. Researchers also found that, similar to now, advancing age was highly predictive of the presence and severity of atherosclerosis.

Thomas explains that the calcific atherosclerosis seen with CT scanning looks just like the atherosclerosis of today and appears in the same locations. While researchers could not determine the exact cause of death in these mummies, symptoms consistent with cardiac chest pain had been described in ancient Egyptian scrolls. In order to understand the lifestyles of ancient Egypt’s elite, the team of researchers worked with Egyptologists to review risk factors that might affect the health of the heart and arteries.

“We suspect, but do not know, that meat, which was certainly leaner at that time, was a smaller part of their diet than ours today,” Thomas said. “We know that Egyptians had an overall better diet, did not smoke cigarettes and were more active – yet they still have the same disease we have. This discovery points to the fact that we don’t understand atherosclerosis and heart disease as well as we think we do.”

Although the findings require further study, Thomas and his co-principal investigator, Adel Allam, M.D., of Al Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt believe these data suggest that genetic factors resulting in atherosclerosis are more important than previously thought. They caution, however, that the genetic factors that may predispose us to the disease are even more compelling reasons to carefully manage risk factors that we have some control over, if not to prevent atherosclerosis, to minimize its impact.

“Recent studies have shown that by not smoking, having a lower blood pressure and a lower cholesterol level, calcification of our arteries is delayed,” said Allam. “On the other hand, from what we can tell from this study, humans are predisposed to atherosclerosis, so it behooves us to take the proper measures necessary to delay it as long as we can.”

Mummies were preserved by going through a 70-day sterilization and dehydration process using natron, a mixture of sodium carbonate, sodium bicarbonate, sodium sulfate and sodium chloride, which allows the bodies to be recognizable and studied 3,500 or more years later. The study was funded by the National Bank of Egypt, Siemens and the St. Luke’s Hospital Foundation. Cardiology co-investigators include: doctors. Randall Thompson of the St. Luke’s Mid-America Heart Institute, Kansas City, Mo.; Sam Wann of the Wisconsin Heart Hospital, Milwaukee, Wis.; and Michael I. Miyamoto of the Mission Internal Medical Group, Mission Viejo, Calif.

This study is published in print and online in the JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging April 2011 edition.

Related Mummy and Archological Cardiology Content:

Egyptian Mummies Show Earliest Cases of Coronary Disease on CT

Mummy’s Secrets No Longer Under Wraps Thanks to 3-D CT

Study Reveals Evidence of Heart Disease in Ancient Egyptian Mummies

Imaging Yields Evidence of Heart Disease in Archeological Find

July 25, 2024

July 25, 2024