MRI-guided breast biopsy with the Suros ATEC system is viewed as one of the patient follow-up protoc

PUERTO VALLARTA, Mexico, March 9, 2006 — The increasing role and mainstreaming of breast MRI in hospitals and breast centers across the country is resulting in more mammographers stepping into the MR suite. And why not? It’s a natural move for physicians to easily transition from reading X-ray and ultrasound images to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and then performing a biopsy in a more traditional modality. The new question yet to be answered is what role does targeted ultrasound play in a breast MR practice?

Connie Lehman, M.D., Ph.D., director of Breast Imaging at the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle, said the role of ultrasound in breast MRI is an important one, offering multiple benefits and some challenges. She presented several practical considerations and logistics of incorporating ultrasound into a breast MR practice and improving the correlation between ultrasound and MRI at a recent breast MRI education conference in Mexico.

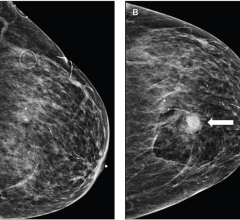

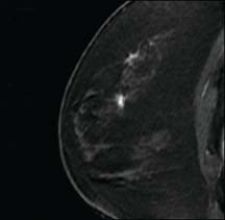

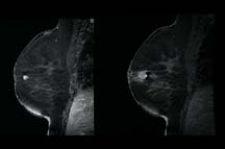

Lehman noted that when she first began doing breast MRI at the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance in 2003, targeted ultrasound was performed on all patients with suspicious lesions on MRI. “We’ve definitely shifted from that model and now proceed directly to MRI biopsy without a targeted ultrasound for some types of lesions,” she said. “We still do perform ultrasound-guided biopsies of MR lesions, but there are many cases we can’t do that and thus need MR biopsy capability in order to diagnose most accurately those lesions we see on MRI.”

The main benefit of ultrasound-guided biopsy is that it’s less costly and offers a more comfortable procedure for the patient compared to an MRI-guided biopsy. There are challenges, however. Targeted ultrasound after an MRI can delay the work-up and can add to the procedure cost if the ultrasound is negative. Gaps in communicating results to the patient can delay an inevitable biopsy or a negative result on ultrasound could encourage a false sense of security. Errors in matching lesions found on MRI to lesions on ultrasound could result in missed cancer diagnoses.

“Ultrasound is a good method to biopsy when you see something under MRI that is seen on ultrasound as well,” Lehman said. “It’s more comfortable for the patient and a less costly procedure. However, cancers seen on MRI can be completely invisible on targeted ultrasound, and I’ve seen many examples of where MRI has detected DCIS or small invasive cancers that were missed on ultrasound. This is not just my personal experience, but can also be found in published data in peer-reviewed literature.”

What women are at risk for exhibiting lesions visible on MRI, but missed by targeted ultrasound? Women with breast tissue that is more fatty than dense and women with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) seem to be at the highest risk of having cancers missed by ultrasound. Even the most ardent supporters of ultrasound don’t recommend imaging in fatty breast tissue due to the difficulty in finding small cancers, and it is well documented that ultrasound is not as effective as MRI or mammography in detecting DCIS. Women with prior surgery also fall into the high-risk category of having cancers missed by ultrasound. Tissue distortion from prior surgery can mask cancers on the ultrasound, and the sensitivity of MRI in detecting small cancers within regions of scarring is better than that reported with ultrasound.

“The sensitivity of targeted ultrasound is not sufficient to negate a suspicious MRI finding,” Lehman said. “It is simply not safe practice to ignore suspicious MRI lesions based on a negative targeted ultrasound.”

Lehman added that given the benefits of ultrasound-guided breast biopsy, targeted ultrasound is a reasonable initial approach to sample suspicious MRI lesions and may be particularly useful for masses larger than 5 mm. But the lack of ultrasound detection does not negate the need for biopsy of suspicious breast MRI lesions. And the guidelines for safe practice are no different for breast MRI than those used in mammography-ultrasound correlations.

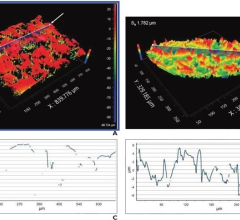

Areas to consider are lesion location relative to quadrant and distance from the nipple, skin or chest wall, size of the lesion, and lesion characteristics. Lehman recommends that hospitals take the time to clearly establish protocol for follow up of patients referred for targeted ultrasound and clearly communicate lesion morphology and location in order to ensure target and acquisition accuracy.

Protocol at the University of Washington/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance dictates making the final recommendation at the time of the MRI interpretation. If the ultrasound is negative and the MRI lesion is probably benign, patient follow-up occurs after a short interval. However, if the ultrasound is negative and the MRI lesion is suspicious, an MRI-guided biopsy is recommended on the report. This removes the risk of the radiologist performing the negative ultrasound not understanding that the MRI lesion needs to be biopsied, regardless of the ultrasound findings.

Lehman said that incorporating targeted ultrasound into a breast MRI practice requires a program for reporting and follow-up that ensures efficient, safe and consistent methodology. And she noted that targeted ultrasound can reduce, but not replace the need for MRI-guided biopsy.

“There are such limited data in this area of doing targeted ultrasound and then biopsy versus follow-up only that we need to see more data published and evaluate it in a careful way,” Lehman said. “We cannot guide our medical practice by anecdotes. The current data published clearly support the need for MRI-guided biopsy in order to have a safe and effective breast MRI practice.”

December 02, 2025

December 02, 2025