Doctors at The National Brain Aneurysm Center in St. Paul, MN, use intraoperative angiography (IA) now in all of its surgical procedures as re-examination of the vascular anatomy may disclose a fundamental misinterpretation of the local anatomy on the part of the surgeon that could lead to an error without the use of IA.

Increases in the number of magnetic resonance images being performed in the state of Minnesota have caused an increase in the number of discovered brain aneurysms in the last 10 years. Many of the unruptured aneurysms were of the severe and complex variety treated via intracranial aneurysm surgery rather than with less invasive coiling procedures.

To ensure best possible results for patients undergoing microsurgery for intracranial aneurysms, the medical team at The National Brain Aneurysm Center in St. Paul, Minn., performed intraoperative angiography (IA) in each case over a 10-year period.

Eric Nussbaum, M.D., chair of the National Brain Aneurysm Center presented the results from the study, IA During Intracranial Aneurysm Surgery. Experience with 1,025 Cases, at the American Association of Neurological Surgeons annual meeting on Tuesday, April 29, 2008. Co-authors are Michael Madison, M.D., Michael Myers, M.D., and James Goddard, M.D..

The primary team of neurovascular surgeon Nussbaum and interventional neuroradiologist Madison focused the findings on cases in which IA altered surgical treatment. They began using IA as a means to ensure the titanium clip used to treat the aneurysm was correctly positioned and did not affect any other vessels, nerves or arteries during the procedure. Dr. Madison performs IA during every intracranial procedure by Dr. Nussbaum.

In 1997, IA added a mean 28.5 minutes to the surgical procedure; by 2006, this was reduced to 10.5 minutes. There were no major complications from any of the IA procedures.

Overall, IA resulted in clip repositioning or the placement of additional clips in 96 cases. Intraoperative angiography demonstrated unexpected aneurysm obliteration in 42 cases when the surgeon suspected additional clip placement would be needed. Those cases most impacted by IA included large/giant aneurysms, lesions with very wide necks necessitating multi-clip reconstruction and those cases in which confirmation of a patient bypass represented a necessary precursor to vascular sacrifice.

Drs. Nussbaum and Madison also found that in a small subset of 30 patients, IA demonstrated completely unexpected residual aneurysm or vascular stenosis. Careful re-examination of the vascular anatomy by Dr. Nussbaum disclosed a fundamental misinterpretation of the local anatomy on the part of the surgeon that would have led to an error without the use of IA.

In an exclusive interview with Imaging Technology News, Dr. Nussbaum describes the logic behind forming the neurosurgeon-neuroradiogist team, how the team operates together in surgery and why he believes intraoperative imaging will eventually become the standard of care for invasive neurological procedures.

Imaging Technology News (ITN): How did you adopt the practice of intraoperative angiography?

Dr. Eric Nussbaum, M.D. (Dr. N): When I did my fellowship, I spent some time up in London, Ontario, with Dr. Drake, who is really one of the fathers of modern aneurysm surgery, He was a tremendous proponent of post-operative angiography. Doing an angiogram after the surgery to make sure that you actually achieved what you wanted to do - mainly to obliterate the aneurysm. When he started doing it, it was pretty controversial, and many people never adopted it because they took the perspective that, well, we’ve done the best we can. The problem with doing post-operative angiography is if you find that the aneurysm is still there that you didn’t appreciate in the operating room, your choice are to either leave it or take the patient back to the operating room. Those were the choices back then before we had less invasive procedures. So it was a relatively big deal and very bold of him to do that. His perspective was that if there is still an aneurysm in there, the patient is still in jeopardy and we need to know that.

Even as early as the 1970’s, Dr. Drake realized that if you could do an angiogram in the operating room, before the head was even closed, that would be the best opportunity to correct the problem. You be able to appreciate residual aneurysm.

Back then they didn’t have the equipment to do a good quality angiogram in the operating room or the image was so degraded that it was that helpful. Then people started to do intraoperative angiography, but not in a widespread fashion.

When I started my practice, I started up front with Mike Madison, who is an interventional radiologist. We said, there are all of those surgeons out there who are worried that coiling is going to take away their business, and there are all of these neuroradiologists starting to coil aneurysms, and take away the business for the neurosurgeon. We decided, why don’t we work together and decide what is best for the patient every time. One of the things that we thought was very important was to have Dr. Madison come into the operating room and do angiogram to minimize complications and maximize the benefit for the patient. I think it has worked out very well.

ITN: When does the neuroradiologist take the angiogram?

Dr. N.: When the head is open, the brain is exposed, you put a clip on the aneurysm, and Dr. Madison, or one of his colleagues, is standing there. One of the reasons centers haven’t started doing this is that it requires a neuroradiologist to be available when you need their help. We can predict when we’ll need their help, but it can vary by 20 minutes or a half an hour, and if they are off doing another procedure, that is a problem. So the neuroradiologist is standing there. We put the clip on, get a digital subtraction angiographic picture, and if there is something like residual aneurysm or that we’ve narrowed a blood vessel that we wouldn’t have wanted to, we can fix it right away. Well before there could be a stroke or any other type of problem.

Why is the neuroradiologist needed?

Dr. N.: You need someone who can take a quality image of a cerebral angiogram and interpret it. Neurosurgeons now who are doing endovascular training could be certainly competent to do the angiogram. You would need either an interventional radiologist or endovascular neurosurgeon.

It would be difficult, but not impossible, for a surgeon had endovascular training to leave the head, do the angiogram, look at the images and then go back up. But you couldn’t have someone who is not very facile with surgical angiography because it is not the most optimal circumstances. You are working under the drape working with a C-Arm and there is a time limit when getting the catheter up to the carotid. So you need somebody who is get interpretable diagnostic images in a quick fashion. If it takes 25 minutes to get the image after putting the clip on, it may be too late to correct the problem.

You are using intraoperative angiography (C-Arm and fluoroscopy) for all intracranial aneurysms procedures. Could you use it for any other clinical applications?

Dr. N.: There might be other areas where we may end up using intraoperative angiography. For example, if we are removing an artery vein malformation (AVM), which is a different type of problem with the blood vessels of the brain, we want to make sure it is completely removed and that the normal vessels look okay. And for some of the bypass work - we actually do a fair amount of brain bypass – analogous to a cardiac bypass – and to ensure that it is open and patent, we’ll do intraoperative angiography in those cases also.

How important is the intraoperative angiography to the patient outcome?

Dr. N.: I suspect that the majority of patients who have aneurysm surgery never have it verified. Basically, they wake up and if they are doing okay, they don’t imaged. Unless they end up getting a follow-up arteriogram or angiogram, you may never know what happened or what the problem was or if there is residual aneurysm.

The use of IA in all of our intracranial aneurysm surgeries gives us a deeper sense of assurance that we have completely corrected the problem, and that we have taken every step possible to ensure our patients' safety.

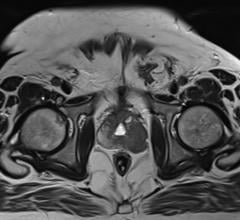

Why do you prefer to a traditional angiogram over an MRA or CTA?

Dr. N.: With newer, pure titanium clips, MR angiography could be used after the image. If you have a very good cross-sectional radiologist, who can help angle the gantry, sometimes you can do a CTA. In general, you really need an angiogram either in the operating room or post-operatively to tell that it has been occluded, and if you’re going to do that, you have to do it right away so you know if there is a problem.

The main reason is formal angiography remains the gold standard for imaging aneurysms. The problem is that to some degree the titanium clip somehow creates artifact and causes difficulty with image interpretation, particularly with CT. There is a lot of scatter artifact with CT and MR as well. Plus, MR takes time compared to an angiogram, and although CT can be very fast, the images can be very degraded. With an average time being 10 minutes, in many cases we’ll have diagnostic images in a minute or two. If we are very worried about blocking something, we will have them stop the surgery, have them put a microcatheter up in the carotid or in the vertebral, put the clip on and then take the picture so we can have an image in 20 or 30 seconds from the time that we have applied the clip.

How have you been able to reduce the time to take an angiogram in the OR?

Dr. N.: I think it’s a matter of everybody involved in the process becoming comfortable and more facile with the technique. You’re in the operating room and you have everything draped and sterile and the operating. One of the jobs of the nurses is to keep everything sterile. So they are immediately suspicious when one of the radiology techs comes in and set up their back table and bring in the C-Arm. You have the radiology techs helping the interventional neuroradiologist do the procedure – passing them catheters and preparing the saline contrast. Then you have the C-Arm person. A lot of it has to do with getting the catheter quickly into the aortic arch, and then catheterizing the appropriate vessel whether it is the internal carotid or the vertebral. Then taking the picture.

As a team, we have gotten better at it. I included that in my presentation because one of the biggest objections to do intraoperative angiography is that it is going to take a long time. But if you do it all the time, it doesn’t add hardly any time to the operation.

What has been the biggest impact from using IA?

Dr. N.: The biggest impact is that our results have been better. We know that because we have cases where it changed what we did. Some of those cases would have resulted in a bigger complication. The most potentially devastating risk of aneurysm surgery is probably stroke.

We published a year ago our experience on unruptured aneurysm and the risk of serious stroke was less than 1 percent. It would have been higher without the use of intraoperative angiography.

One of the criticisms has been the radiologist could cause a stroke during the angiogram. But we have not seen that at all.

Is there an increased infection rate from performing the intraoperative angiography?

Dr. N.: I think that is theoretical because we’re only talking about 10 minutes of added time. I can’t say there are any cases that I would attribute infection to the intraoperative angiography. We have an infection rate of less than a half percent and that is within or below the average for elective craniotomy procedures. We don’t have any evidence that it caused any infection.

Could intraoperative angiography become part of the standard procedure?

Dr. N.: I think some form of intraoperative confirmation of what you have done should be used in every case. I suspect it will be used more frequently in the future as neurosurgeons are held to a higher standard. Because there are less invasive techniques, coiling techniques, open surgery, they won’t be able to get away with clipping the aneurysm and not knowing that you have done what you have

I think intraoperative angiography will become more widespread and potentially standard.

Could it include other types of imaging devices?

Dr. N.: They are you using intraoperative MR and CT and if they develop the right software packages, then it could possibly used in the future.

August 14, 2025

August 14, 2025