Greg Freiherr has reported on developments in radiology since 1983. He runs the consulting service, The Freiherr Group.

Why the Use of PET/CT in Radiation Therapy Requires Thinking Outside the Box

Graphic courtesy Pixabay

The intersection between PET/CT and radiation therapy is widening. And it is doing so in unanticipated ways.

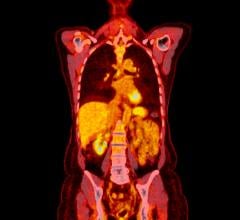

You might expect this hybrid’s potential against cancer to be found in its natural proclivity for the visualization of malignant tumors, one that has grown more sensitive with the advance of PET technology. Or perhaps you might predict an enhanced ability to see the earliest signs of cancer from the increased sensitivity or localization possible through advances in CT. You might also expect the use of this modality’s unique combination of functional and anatomical data to be leveraged in the planning of therapy, possibly in place or in combination with CT simulators now in use.

But there is where you would be wrong.

Little has come from more than a decade of forward thinking in the latter direction and little is likely to come of it. That does not mean, however, that PET/CT will not have a role to play in the planning of cancer therapy. Far from it.

PET/CT’s biggest opportunity in this regard may stem from the insights this modality can provide about the metabolic pathways of this disease. This potential has been taking shape over the last several years in studies of an enzyme implicated in the occurrence — and treatment — of cancer.

The enzyme, called deoxycytidine kinase, is associated with certain types of cancer. One of the first reports of how PET/CT might use this enzyme to visualize and monitor cancer surfaced about six years ago in the Journal of Nuclear Medicine. The research, conducted in mice, has since been extended to human subjects. Plans for formal clinical trials are now in the works.

The development of a PET agent for this enzyme is still years in the future, as is a commercial radiopharmaceutical that might be widely available. Neither one is a sure thing. But the research may demonstrate how PET/CT could make its long-awaited impact on therapy planning.

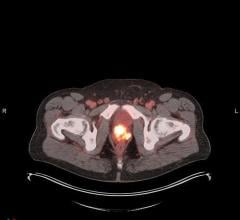

In the meantime PET/CT is proving useful as an adjunct to more conventional efforts to visualize and destroy cancer. Recently, the hybrid has been used effectively by research teams in England to identify and guide the removal of cancer cells that remain after the treatment of head and neck cancer. Its use in tracking down elusive malignancies might be leveraged to eliminate the need for patients to undergo invasive post-treatment surgery.

It is encouraging to see such reports, just as it is sobering to realize that PET/CT has not lived up to past expectations, ones that would seem less difficult to achieve.

Peer-reviewed literature abounds with the potential once imagined for PET/CT in radiotherapy planning. Just years after the these two modalities were put together, oncologists and radiation therapists began exploring how the unique combination of structural and functional information might afford better targeting of tumors, according to their distribution, size and metabolic activity.

More than a decade ago the idea appeared of applying these capabilities in the form of a dedicated PET/CT simulator. One paper, published in 2005, concluded that such a simulator could reduce radiation exposure of healthy tissues, thereby intensifying the dose administered to malignancies. Already two years earlier the idea of using PET/CT as a treatment planning tool for conformal radiation therapy had been proven feasible. The paper describing this research, while noting the potential for reduced risk due to minimized dose being applied to healthy tissues, concluded that “the impact on treatment outcome remains to be demonstrated.”

And therein may lay the rub. While the potential of PET/CT and radiation therapy has long been recognized, the challenges standing in the way of its widespread use for the most obvious application in radiation therapy have been formidable. These may be less technological than political and logistical.

First and foremost is the lack of reimbursement for the use of PET/CT in radiotherapy. Second is the fact that PET/CT and radiotherapy planning are done in two different departments — one nuclear medicine; the other radiation therapy. Third is staff training.

While there may be other reasons, these would seem difficult enough. Consequently, realization of PET/CT’s potential in therapy would seem to require thinking outside the simulators — and turf — of radiation therapy planning, as it is practiced today, and more in line with the metabolic pathways that that define the strengths of this hybrid.

Editor’s note: This is the second blog in a series of four by industry consultant Greg Freiherr on Where Molecular Imaging Fits in Managing the Cancer Patient. To read the first blog, “How to Achieve the Quantitative Promise of PET/CT,” click here.

July 30, 2024

July 30, 2024